---

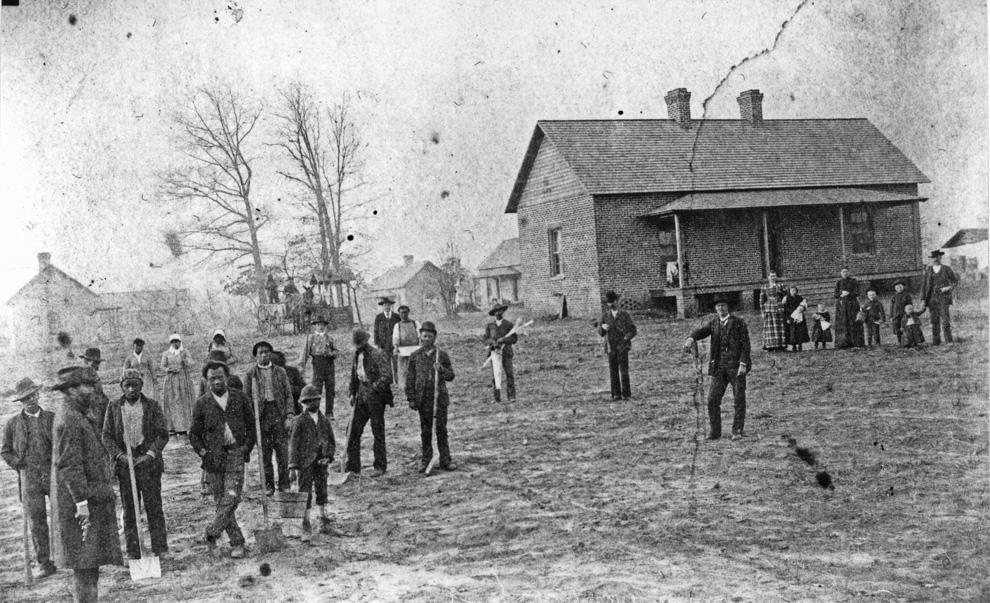

Prison Farm / County Home, 1880s.

(Courtesy Durham County Library / North Carolina Collection)

On November 15th, 1881, the County Commissioners purchased a tract of 138 acres of land on Roxboro Road, then about three miles north of Durham, from WA Wilkerson for $1393.75 and erected a frame house for "the care of the aged, indigent and infirm." Brodie Duke, who owned a furniture store at that time, sold the county furniture for the facility. They appointed John W. Evans as superintendent of the facility. In March 1882, the county commissioners also decided to build a prison/work house "for the confinement of criminals undergoing sentences of not over ten years" was constructed "separate and apart, however, from the cottages of the unfortunates of the first named class."

Prison labor, and labor provided by able-bodied, impoverished residents, was used to maintain the facility, including cleaning, cooking, and tending the farm on-site to provide food for the inmates and residents of the poorhouse. The prisoners also did off-site labor such as road work and "such other manual labor as comes least in conflict with free labor."

County Home, 1881.

(Courtesy Duke Rare Book and Manuscript Collection - Wyatt Dixon Collection)

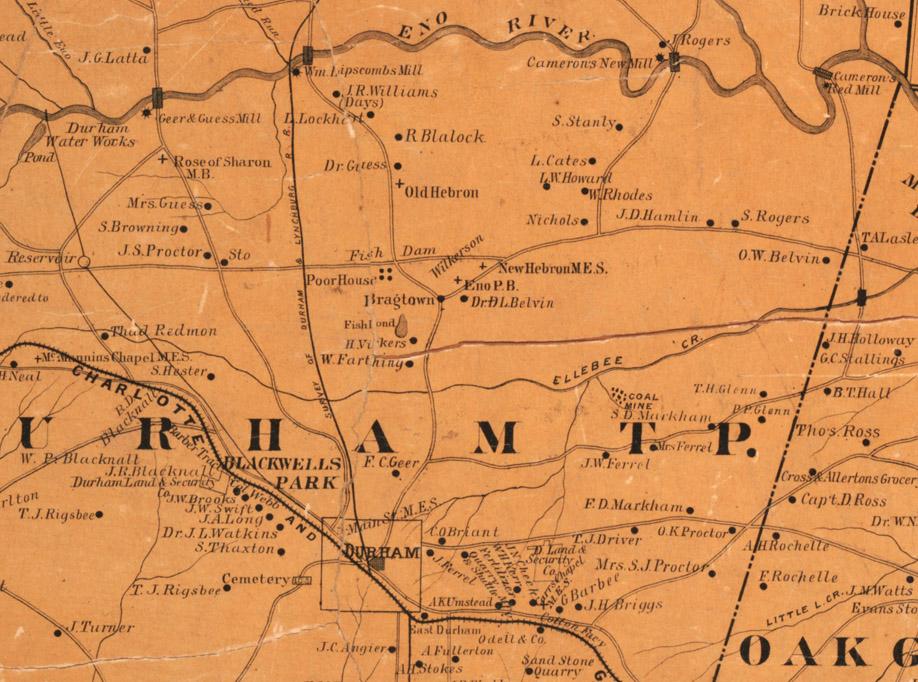

1887 Map of Durham showing the location of the 'Poor House'.

Mangum's 1887 Directory of Durham gives a description of the facility:

"Within the last few years the lands have been brought into a high state of cultivation, whilst neat and well ventilated cottages (some of brick), have taken the place of the poor cabins that formerly served as shelter for the unfortunates whose only crime was being poor and mentally or physically infirm. The poor inmates are now well-housed, clothed and fed, and are surrounded by Christian influences and accorded humane consideration in striking contrast with the neglect, squalor and savagery that prevails at some similar institutions in some counties of the State. Here God's poor unfortunates find a home indeed, instead of a 'poor house' and an inferno. Here they are not surrounded by humiliating reminders of their helpless dependency. A neat Chapel has recently been erected, where lay services are held every Sunday afternoon. To the untiring efforts of the present Superintendent, aided by his subordinates, and supplemented by the Board of Commissioners and County Physician, much praise is due for the truly satisfactory condition of this institution."

By state law, each county appointed a warden of the poor (later re-branded superintendent of public welfare) who maintained a roll of those considered the 'outside poor' - what we would refer to as homeless - these rolls were not regularly monitored, and forms of assistance could range from financial to work to housing at the county home. Despite the impetus to establish some form of facility to provide some accommodation for people who were certainly considered society's 'undesirables,' (n.b., three miles out of town) conditions in the county home were less than optimal, as you might imagine. The below is from a Master's thesis on Durham County's impoverished, by Rebecca Thaler:

In 1890, the county commissioners requested that a grand jury investigate John W. Evans, the superintendent of the poorhouse and workhouse since their creation almost a decade earlier. In the ensuing case, the county charged Evans with mistreatment of paupers and prisoners, misappropriation of county funds, and general mismanagement. One witness, J.L. Massey, who had served as prison guard for fourteen months, testified that Evans designated certain prisoners as “trustees” and let those men have the run of the grounds. Evans allowed one trustee, a Mr. Hicks, to leave the grounds altogether, “being at liberty to spend his nights and Sundays at his home” five miles away. Massey also testified that Evans “lets them [the trustees] eat at his own table” along with the superintendent’s family. The county commissioners appear to have been justified in their concern that Evans allowed at least some prisoners to have the run of the poorhouse grounds. The Grand Jury also investigated two cases in which Evans was accused of cruelty and neglect of a poorhouse inmate. When William Cameron, a black pauper, had been admitted to the county home the summer before, he had been suffering from gangrene in his foot. A local doctor who attended to poorhouse inmates amputated Cameron’s foot; then, a few days later, the doctor found that “the disease had advanced up his leg” and performed a second operation to amputate more of the man’s leg. Cameron’s leg, exposed in the summer heat, “became infected with maggots,” and he died shortly thereafter. Several paupers testified that Evans had been left unattended. Another black man living in the poorhouse, Jesse Mosely, had an “unexpected hemorrhage of the lungs” and died unattended, “suffocating in a pool of his own

blood.”

Although the Grand Jury concluded that “the management of the Poor House is by no means what it should be, being in many respects worse than can be imagined,” the testimonies of guards, doctors, and paupers offered a mixed assessment. The county commissioners ultimately ruled that Evans had not committed “any criminal act or neglect” and retained him as superintendent until Evans quit.

By the 1890s, the county home had been enlarged to 9 frame buildings; on a state level, housing of criminals with the impoverished had come under some fire. In one particularly colorful quote, which gives you a sense that not a few of the convicted were prostitutes, Rev. G. William Welker chairman of the State Board of Charities opined that “the respectable, aged, and infirm pauper is shut up with the wornout strumpet, whose very presence is pollution.” Particularly of concern was the rise in children living at the county home - both those that had come with their families, as well as those born at the home. Much of the rise of private charities in the 1890s and early 1900s arose from the failure of the county home to provide adequate care and housing - in particular to those considered 'worthy'. White children epitomized that 'worthiness'.

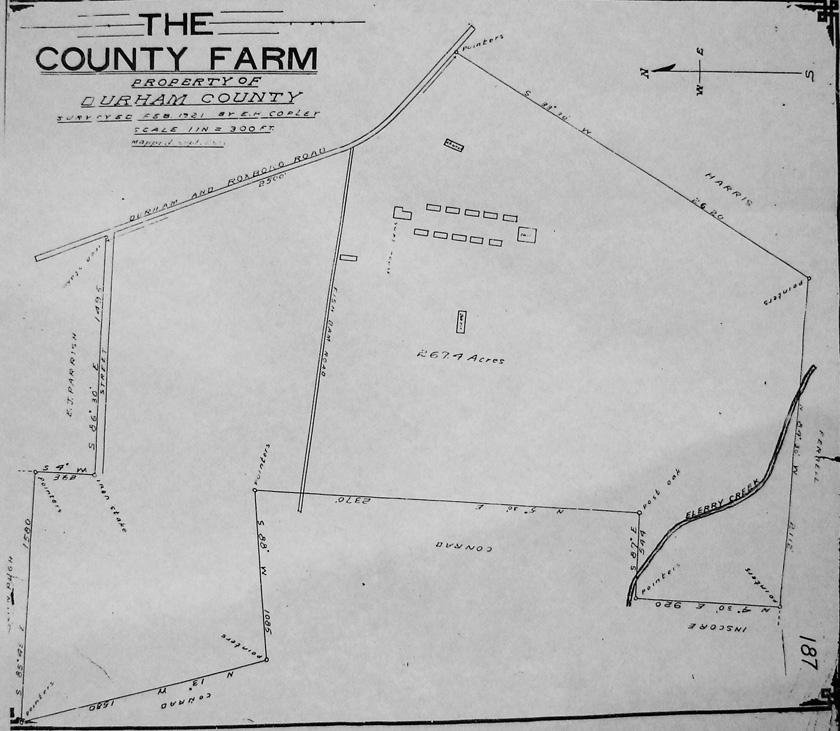

1921 Survey Map, retrieved from the Durham County Register of Deeds.

(Provided courtesy of David Southern and Steve Rankin)

By 1925, a new Durham County jail had been built approximately 3/4 mi. west of the county home on Broad Street. At least some of the prisoners formerly housed at the county home were moved to that facility, alleviating some of the discomfort arising from the co-housing of the impoverished with misdemeanants. A new County Home main building was built that same year at a cost of $175,000, and the facility became primarily used to house the impoverished and disabled.

This use began to wane during the 1930s; Anderson notes that, by 1937, county homes / 'poor houses' were being downsized, their functions supplanted by the rise of Federal and state programs to provide social security and welfare benefits. Durham's persisted, however, providing primarily housing to disabled people.

County Home from N. Roxboro Road, 11.06.58.

(Courtesy The Herald-Sun Newspaper)

In 1960, Durham County Memorial Stadium was built on a a portion of the county home land, closer to North Duke Street. It primarily provided a football facility for local high school teams.

Aerial of the county home site, around 1960, looking north. N. Roxboro Road runs into the background on the right, North Duke St. on the left. The then-new county stadium is visible, and the county home and farm outbuildings are to the right.

(Courtesy The Herald-Sun Newspaper)

Durham County Stadium, 1960

View of the County Home and outbuildings looking east towards Roxboro, 1960, with a small portion of the stadium visible in the lower right-hand corner

County Stadium, with the National Guard Armory in the background, 1960.

By 1973, the County Home buildings were demolished and replaced with Durham Regional Hospital.

The county stadium has hung on since then - in 2003, the county pondered tearing it down, but eventually decided against it.

04.11.03

The stadium

The stadium remains in regular use as of 2011, having just undergone a major renovation by the county. Per Wikipedia, sourced in September 2011, the stadium :

is mostly used for high school football and soccer but also serves as the home field for theBears of Shaw University despite the school's location in neighboring Wake County. Durham County Stadium is the current home for the Triangle Rattlers Semi-Professional Football Team. The minor league organization represents Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill, as well as the surrounding area. The stadium is also one of North Carolina's main archery venues.

Comments

Submitted by Eddie (not verified) on Sun, 1/6/2013 - 2:54pm

My dad used to work at the Armory and I learned how to drive in the stadium parking lot. He made me drive a 1966 Ford Country Squire station wagon in reverse around the whole stadium. I later marched in a Northern football game with the Marching Knights. Great memories.

Submitted by Joseph Sparks on Sun, 11/2/2014 - 7:23pm

I played Junior High football here many times for Carr Junior High. Good times and memories. I also attended an evangelist's crusade meeting here which had the featured speaker as the now famous televangelist, Reverend Jack Van Impe when he was just getting started. His claim to fame then, not to sound detracting of him either, was that he had memorized the entire New Testament of the King James Version of the Bible. This was the mid 1960s if I remember correctly. Great stadium though and I also went to several "Battle of the Bands" concerts there. Mostly always local talent.

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.