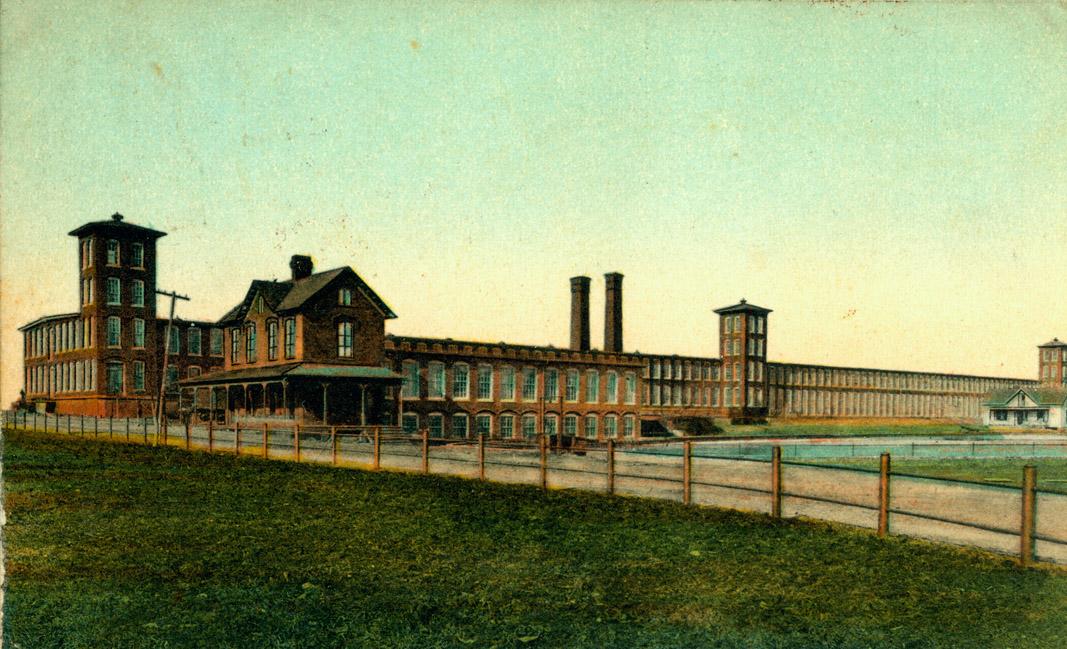

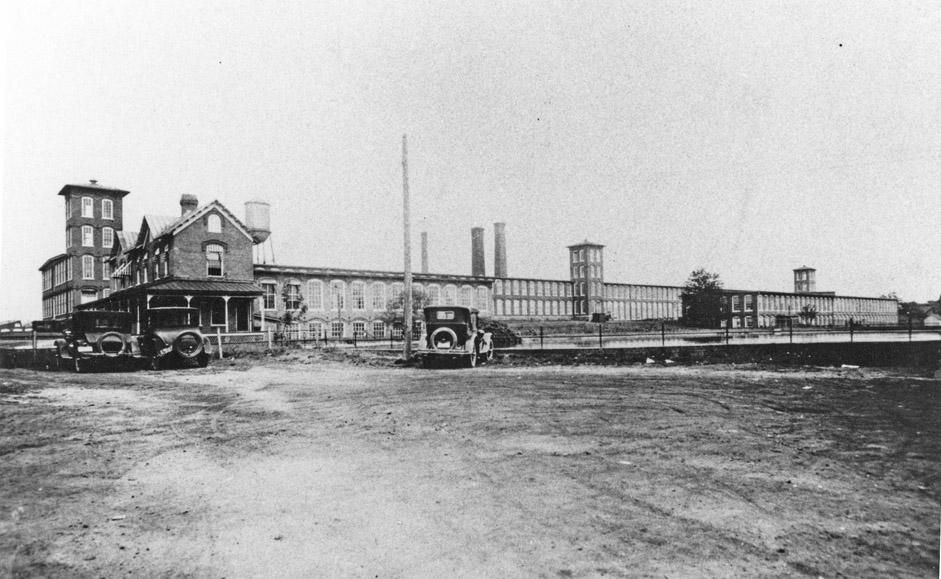

Erwin Mill No. 1 and office building, early 20th century

(Courtesy John Schelp)

Julian Carr's success with Durham's first textile manufacturing plant, the Durham Cotton Manufacturing Company, which returned 20-30% net profit in its first 6 years, showed the viability of the industry in Durham and, more broadly, the south.

The Dukes, who had followed Carr's lead 10 years earlier - establishing W Duke and Sons tobacco Co. in the wake of Carr's success with Blackwell's Bull Durham - sought to repeat the model in the textile field. Carr had proved the market; the Dukes would seek to build it better and more profitably.

George Watts and Ben Duke recruited William A. Erwin from Burke County, where he had grown up on the family plantation of Bellevue near Morganton as part of the Holt textile family, purportedly on the recommendation of Southgate Jones. Erwin was 36 years old when he came to Durham, but not inexperienced; for the previous ten years, he had been treasurer and general manager of the EM Holt Plaid Mills in Burlington. Erwin confidently told Ben Duke that he could derive 40% net profit from the business they were to establish. Erwin invested $40,000 in the venture, while Ben Duke and George Watts invested $85,000.

The group sought additional investment from northeastern textile manufacturers, who were disinterested. Duke and Watts provided an additional $75,000 in capital to start the venture. Duke was emotionally invested in the success of the project as well - terming it one of [the Dukes'] "pet enterprises."

Repeated in every single source referenced by me is the same anecdote regarding the naming of the mill after Erwin. I'll repeat it despite the fact that it sounds made-up-after-the-fact to me. After some discussion of what to name the new venture, BN Duke remarked "Let us name it for this young man; then if it fails the onus will be upon him; and if it succeeds, it will be to his glory." So it was that the venture became the Erwin Cotton Mill.

Construction began in the Fall of 1892; the company bought several adjacent tracts of land in West Durham and built a 75 x 347 foot, two-story factory, a picker building, dyehouse, boiler room, engine house, and office building. The company began the construction of residences to the west, north, and east of the textile factory.

The factory began by producing muslin, used for tobacco bags, but, at Erwin's directive, began to produce denim, which, up to that time, had not been produced in southern textile factories. The mill's production grew rapidly, almost tripling the following year, thereby becoming the textile mill with the highest production in Durham. By 1895, the factory had 375 workers working on 11,000 spindles and 360 looms to produce fine muslin, chambrays, camlets, and denims. By the next year, the company had 1000 workers, 25,000 spindles, and 1000 looms. Erwin Mill became one of the largest denim producers in the country.

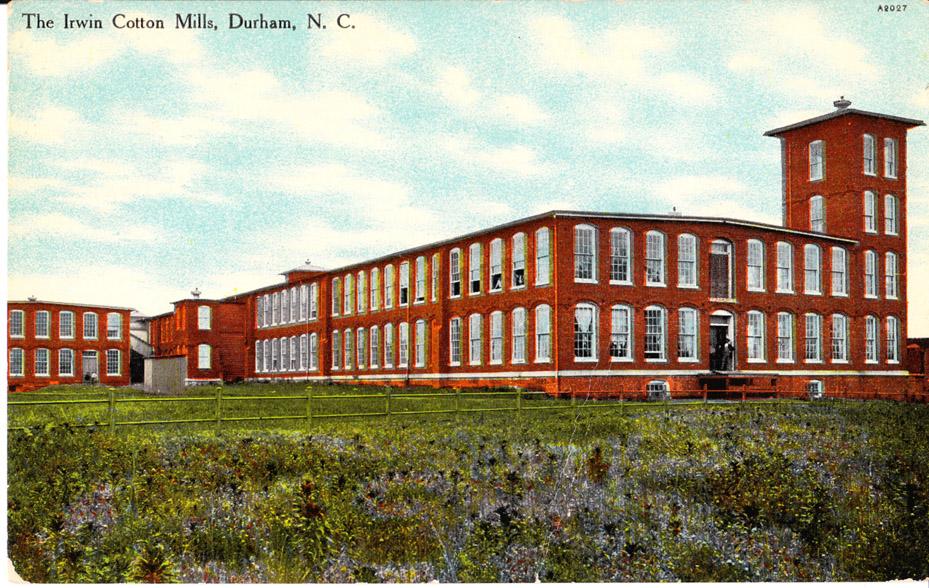

The "Irwin Cotton Mills" - looking north

(Courtesy Dave Piatt)

Erwin was secretary-treasurer of the company, the title bestowed upon the chief operating officer. He recruited Edward K. Powe, an executive at the Altamahaw Cotton Mill in Alamance County, to be plant manager. Erwin set out to build a self-contained community as well as a factory; a company store was established at West Main and Ninth Street [which contained a post office], a meeting hall was built, and, by 1900, 440 houses had been built in the area around the mill.

One the primary 'advantages' that a southern textile mill had over the well-established northern mills was southern poverty, and the resultant ability to pay workers low wages. Per Robert Durden, in 1890, a "skilled man" received average daily wages of $1.00 to $2.50, a "skilled woman" 40 cents to $1.00, and children from 20 to 50 cents. Yes, child labor was alive and well during this era, and a high percentage of factory workers were women and children. In the progressive cost calculus of Richard Wright, coal cost $3.15 to $3.25 a ton, and "girls could be had from $2.50 to $4.00 a week." Erwin mills would, during the 1890s, run 66 hours a week and employ children older than 12. By the early 20th century, the large northeastern textile manufacturers had started moving their operations southward to utilize these 'advantages.'

Success of the venture necessitated expansion in relatively short order; in 1898, the original mill building was expanded to twice its original size by lengthening the building to the north. The original two end towers became the south and middle towers, and a third tower was added to the north end. An addition was added to the rear (north side) of the office building, and its cupola was removed.

In 1899, the Pearl Mill, a Brodie Duke venture came under the management of Erwin as well (it had been reorganized by the other Duke brothers and Watts in 1895 following one of Brodie's financial reversals.)

The success of the Erwin Cotton Mill sparked a period of expansion. Mill No. 2 was constructed on the Cape Fear River, beginning in 1902 - the associated mill town would be called Duke, but later renamed Erwin so as not to evoke confusion with Duke University. Mill No. 3 was constructed in Cooleemee during 1901-1906.

The Erwin Cotton Mills company was financially successful venture; in 1904 the board of directors declared a stock dividend of 200%, and the Erwin announced a net profit of $215,000 - a $30,000 increase from the prior year.

In the early decades of the 20th century, workers began to prove harder to attract than during the repeated economic depressions of the 1890s; Erwin decreased work hours to 62 hrs 40min a week in Durham to help retain and attract labor. Contraction of the textile market after the Spanish-American war did not help matters. Sales continued to decline significantly during the latter 00s; Erwin and Ben Duke organized agents to sell Erwin textiles in Asia in hopes of opening new markets. Duke and Erwin pushed hard for increasing protective tariffs on imported textiles, which did not succeed. In 1913, the Congress reduced tariffs on imported goods from previously high levels. However, the macroeconomic climate appeared to be improving to a point that the company could succeed in a reduced-tariff market, and profits once again grew during the 1910s.

By 1907, a cotton storage house and several brick structures for "beaming and slashing" had been added to mill no. 1.

When Erwin announced that the company would expand to a fourth mill, he would not state where the mill would be located - he teased the city of Durham with the notion that the mill would be constructed in Durham, but refused to commit to doing so. Durham had designs on the incorporation of West Durham into the municipal fold, but Erwin wanted none of it; West Durham was a mill town, and his mill town at that. When Erwin said that the mill would be located in the city that "offered the best advantages" Durham backed away from annexation. Mill No. 4 was built along Mulberry St. immediately to the west of mill No. 1 in 1909.

Erwin Mill No. 4, looking northwest from Mulberry St., 1910s.

(Courtesy Duke RBMC - Digitized by Digital Durham)

Full panoramic shot of Mills No.1 and No.4, looking north from Mulberry St., 1910s

(Courtesy Duke RBMC - Digitized by Digital Durham)

Part of Mill No. 4, and the mill village stretching westward, 1910s.

(Courtesy John Schelp)

It didn't take terribly long after the establishment of Durham's tobacco and textile factories for initial talk of unionization to take hold—the Noble Order of the Knights of Labor, founded in Philadelphia in 1869, had five assemblies in Durham by 1888. In 1900, a union organizer reportedly managed to sign up 191 workers at the Erwin Mill; the reasoning was to try to establish a mutual aid fund (the precursor to health insurance, which typically also provided death benefits) that Erwin had been unwilling to provide or meet with them about. Once the unionized people were on their knees from lost wages, Erwin made a show of 'taking them back' and alleviating their distress. People would be helped / charity would be given, but on Erwin's terms.

Labor conditions would begin to change slightly by 1913, when night work was restricted to 7-9pm and 1916, when the minimum age for employment was raised to 14.

Erwin Mill, 1913.

Erwin, not infrequently referred to as 'Pa' Erwin, truly acted the part of the father figure in West Durham, and the flip side to his paternalistic control of the lives of mill workers was a genuine concern for the well-being of his community. He offered 11 weeks of free night school to workers, and financially supported clubs, libraries, and nurseries for the workers. He repeatedly referred to the employees of the mill as "my people" and, per multiple anecdotes, seemingly knew every worker by name. He freely supported churches and community organizations. Failure to live by his standards, though, could exact harsh penalties. Erwin would ride his bicycle around the neighborhood to ensure that residents adhered to a 10pm 'lights-out' rule. Arrests for public intoxication were grounds for dimissal from the mill, and loss of housing. Various other moral transgressions could result in similar penalties. Many of those shunned often went to live in 'Monkey Bottom' - the low ground to the southwest of Erwin Road and West Pettigrew between Swift and Oregon Sts. (now Erwin Field.)

Mill No. 1, 1920s

(Courtesy Durham County Library)

The construction of Erwin Auditorium in 1922 provided recreation facilities for the community, as did the adjacent Erwin Park and Erwin Field one block away. A zoo, playground, and tennis courts accompanied Erwin Auditorium; community events in and around the auditorium were frequent.

Control of the company over the mill village began to slip by the mid 1920s. Erwin's opposition to the annexation of West Durham could not hold, and the city incorporated the village into the city in 1925. Increases in factory mechanization led to a faster and faster pace of work for employees, who struggled to keep up with the pace of the machines. Dissatisfaction with working conditions created fertile territory for union activity to gain greater traction at Erwin Mill. National legislation during the New Deal would lead to protection of workers' right to organize, established a 25 cent/hr minimum wage, 40 hour work week, and control of child labor.

Erwin Mill No. 1, office building, and cloth and shipping buildings, looking west-northwest from near 9th Street, 1920s.

(Courtesy Durham County Library)

By the early 1930s, Erwin had become ill with cancer; he died in 1932. He was succeeded by KP Lewis. To Lewis, Erwin had written in 1926:

"I urge upon you to keep in mind that we cannot let go the cordial enterprising spirit which it has cost us much to establish in our villages and in the hearts and minds of those serving our Company in a responsible way, for the spirit and soul of our business is the life of our business and has roots deeper in same than what we call 'policy'. We must treat everybody right, but must keep in mind that our stockholders come first."

Hanging onto the old 'cordial enterprising spirit' would be a challenge for Lewis, as putting the stockholders' demands for greater output first had caused dissension in the ranks, as demonstrated by increasing unionization. Tobacco workers in the city had begun to organize during the 1930s as well, as had building trades in Durham. In March 1934, a union meeting was held at "West Durham High School" - KP Lewis utilized spies to gain information about the organization attempts of his employees. Dropping wages (a 63.5 drop between 1920 and 1934) had helped foment workers' complaints. Management felt that the dissatisfaction was being sown by so-called 'flying squadrons' - union leaders from elsewhere who would come to communities and "try to disrupt [their] operations."

Increasing unionization of employees and dissatisfaction with working conditions and wages led to a general strike of thousands of textile employees throughout the southeast begining on labor day - September 3, 1934. Per the N&O several hundred striking Erwin Mills workers met to form their protest at the Carolina Theater and marched down West Main St. to Erwin mill, where they confronted president KP Lewis over better working conditions. In total, 5200 workers in Durham from Golden Belt, Durham Hosiery Mill No. 1, the Durham Cotton Manufacturing Company, and Erwin Mills participated in the strike.

At the end of the strike, though, little had changed, and union membership decreased in Durham.

By 1937, the Textile Workers Organizing Committee had unionized all five Erwin mills. Erwin Mills, and Lewis, seemed to accept the unionization of their workers with less bitterness than most industrial employers, although Lewis continued to chafe at negotiations with union representatives rather than directly with employees. Difficult working conditions changed little leading to repeated strikes over the subsequent decades.

Opinions of the working conditions at Erwin mill obviously varied widely, given all of the factors that influence people's opinion of their jobs both then and today. While some oral histories bemoan the very difficult working conditions, other histories speak to how wonderful a job at Erwin mill was compared to what else was (or wasn't) available. I quote from an oral history of James Jackson, resident of 715 15th St., from September 1938:

"I don't know of a better company to work for," he declared. "The officials here have the worker's interests at heart. They've furnished us with a fine Auditorium where a person can find free amusement if he wants to. They order coal in big lots and sell it to us without profit for $6.50 a ton. They keep the houses in good repair and rent them to us for almost nothing. I pay $1.50 a week for my four rooms, bath room, and garage. If I didn't live in a company house I'd have to pay $5 a week for a house not kept in as good condition to this.

"There are very few people working in the mill who make less than $12 a week when they work full time. Some of the help's sent out now and then as much as a day out of a week to rest but never more than that. We make standard goods -- sheets and pillow cases, you know -- and we generally have orders on hand all the time.

"I feel like people living here at this mill have as good or better chance for a decent living as most people working in stores, in offices, and such places where they don't make any more than we do and have a sight more house rent to pay.

"Of course the company don't have enough houses for all its help. There's some working in the mills here that's paying $20 a month for rent because they caint get a company house. But the majority of us has the advantage over other working people when it comes to rent."

The company continued to expand during the mid-20th century. The Pearl Mill officially became Erwin Mill No. 6 in 1932. In 1948, the Diana Mills in Wake Co. became mill No. 7 and the Stonewall Mills in Stonewall, MS became Mill No. 8.

Erwin Mills, looking southwest, 1930s

Erwin Mill was the recipient of government contracts during World War II; as with most industry, strike activity was put aside in the name of the war effort. Erwin Mill added a third shift to meet increased production demands. During the war period, the mill began to sell off its mill housing - beginning in 1942. Most of the housing north of the railroad tracks was sold off to employees in subsequent years.

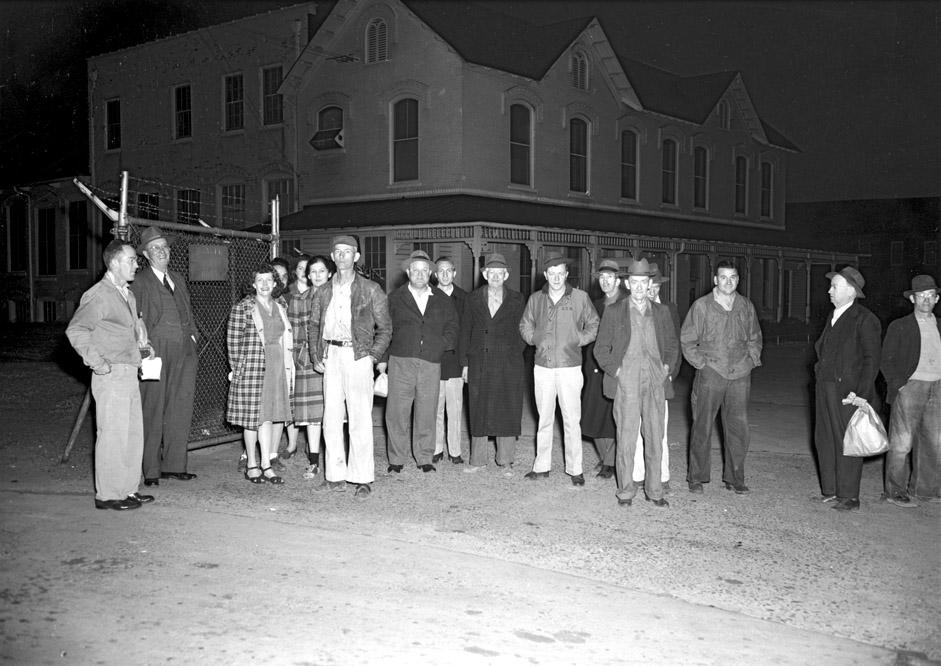

Second or Third shift workers outside of the Erwin Mills office building at night, 1940s

(Courtesy the Herald-Sun)

Interior view of one of the two mills in Durham, 1940s

(Courtesy the Herald-Sun)

Immediately after the war, labor unrest began anew.

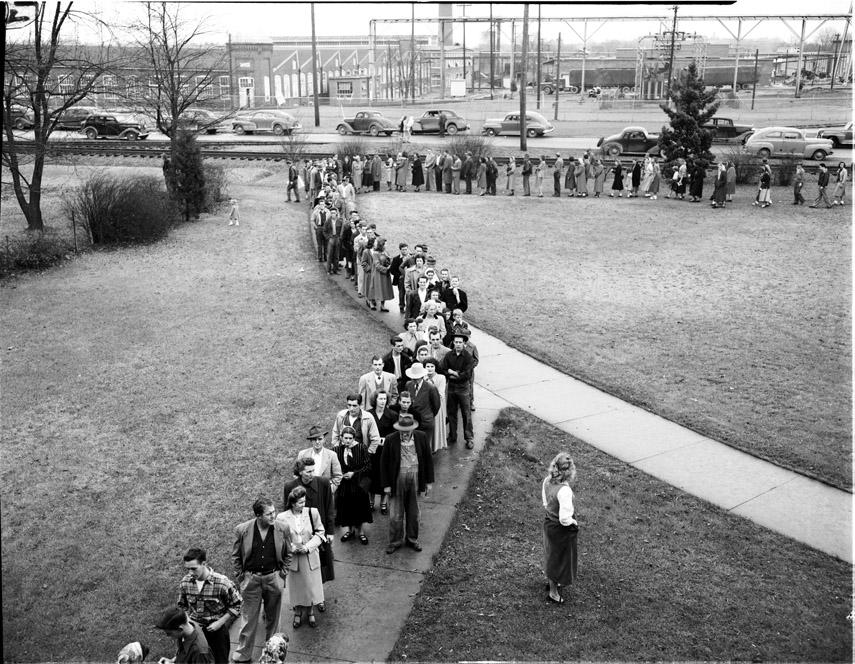

Erwin Mills strike, 1945 - looking northwest from the south side of the railroad tracks, in front of the Erwin Auditorium, towards Mill No. 4

(Courtesy the Herald-Sun)

One sign reads:

" $5

40 Hours

$2200 ?

It won't support a

Familey"

Another reads:

"1892-1945 = 53 years ........ as poor as ever."

Erwin Mill Strike, 1945, looking north at Mill No. 1

(Courtesy the Herald-Sun)

Things were somewhat different this time. In 1948, KP Lewis would resign as president of the company and became chairman of the board of directors. New President William Ruffin succeeded KP Lewis, and seemed to change the tenor of relations between the company and it workers. Ruffin had hired Duke University economist Frank T. DeVyver in 1943 (while a member of the board) to study production at the plant. DeVyver enjoyed a good relationship with the union, set up an employment office, grievance procedures, and other methods for employees to direct feedback to the company. The 1945 strike ended with management agreeing to all requests, including 65 cents/hr pay, a 45 minute lunch, and one week of vacation for employees with less than 5 years experience, 2 weeks for those with greater.

By 1951, the company owned 8 spinning and weaving mills as well as two finishing plants with over 220,000 spindles and 6000 looms which consumed 140,000 bales of cotton a year and produced 165,000,000 yards of cloth. The company employed 6400 people. The major products of the Durham mills were sheets and pillow cases, made in "three popular muslin grades." Other mills produced a variety of other types of cloth.

Another strike that same year, called for by the national union, was considerably less amicable, as workers attempted to blow up parts of the mills.

Erwin Mill Strike, 1951; looking south from Mulberry St. towards Erwin Auditorium

(Courtesy the Herald-Sun)

Striking workers marching west on Mulberry St., 1951 with the Erwin Mills office building and the West Durham Post Office in the background.

(Courtesy the Herald-Sun)

Perhaps that was the breaking point for several of the stockholders of Erwin Mills, as by 1953, they sold a controlling interest in the company to Abney Mills of South Carolina, which would use the plants for production of sheeting. The true impetus was more likely, per William Ruffin, an inheritance tax problem. John Sprunt Hill, who, as the son-in-law of George Watts owned 20% of Erwin common stock, fought ceding control of the mills to a South Carolina Company vigorously. When he lost a bid for Mary Duke Biddle's stock to Abney Mills, he tied the transfer up in court for a "protracted period." Hill was evidently opposed to changes at the mill instituted by Ruffin, although it isn't clear what he specifically objected to. Hill lost the battle.

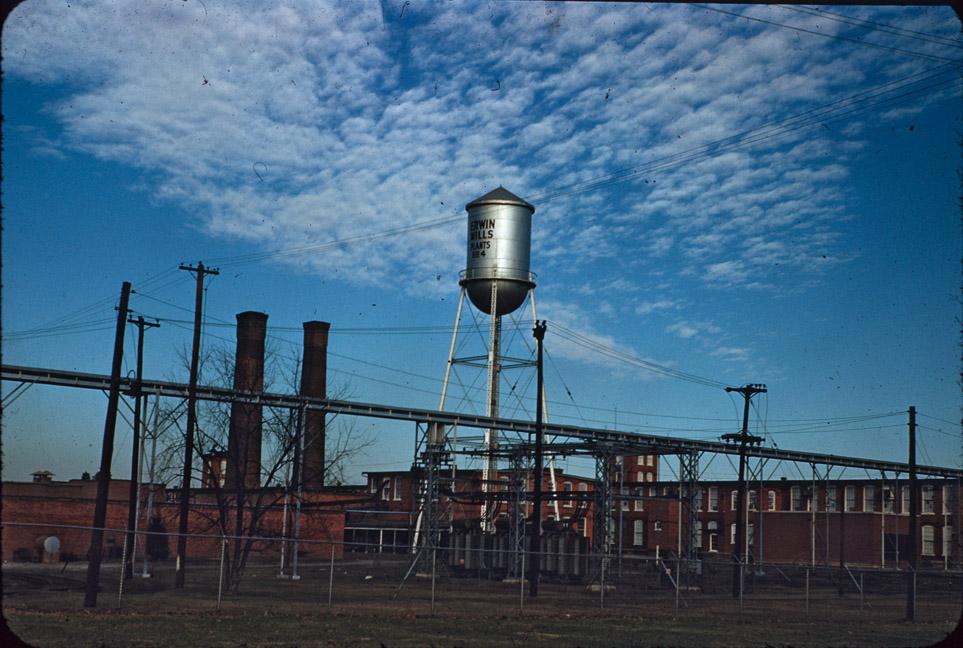

Erwin Mills, 1950s

(Courtesy Durham County Library)

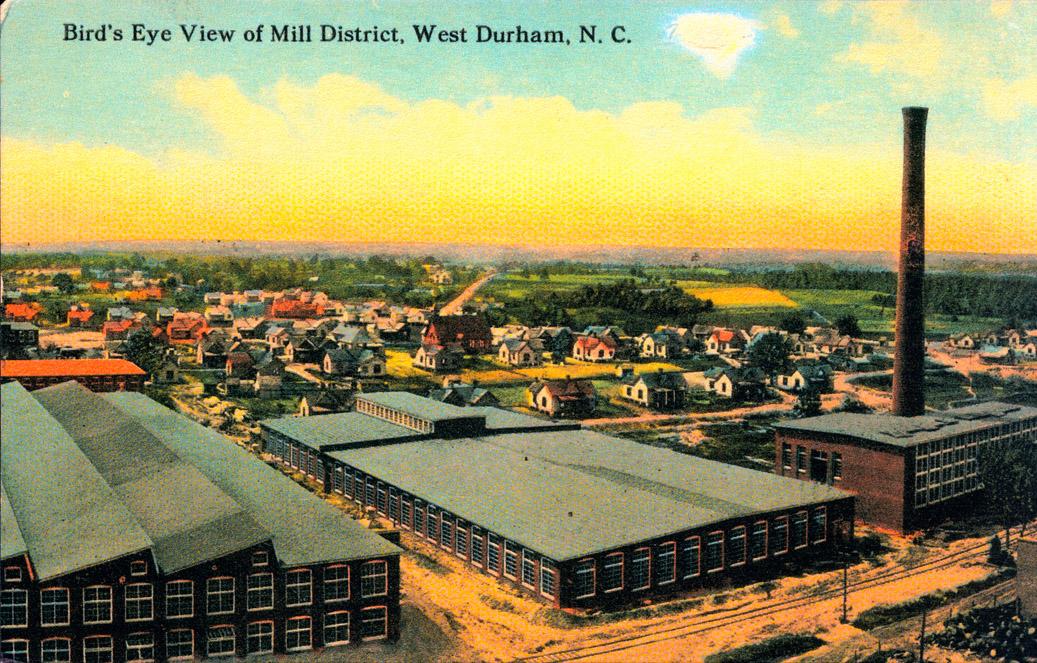

Erwin Mills and surrounding mill village, bird's eye view looking east from ~ above 15th street.

(Courtesy the Herald-Sun)

Between Mills No. 1 and No. 4, near Mulberry, looking northeast towards the back of Mill No. 1, 1951.

(Courtesy Duke University - Lewis J. McNurlen Collection)

Apparently a manger scene on Ninth Street, looking west towards the Cloth Building with Mill No. 1 behind it, 1951

(Courtesy Duke University - Lewis J. McNurlen Collection)

Looking west at the non-connected Main and Mulberry Streets in front of the mill, 12.05.51

(Courtesy The Herald-Sun)

Two Watchmen at Erwin Mills, 05.27.53.

(Courtesy The Herald-Sun)

In 1962, control of the mills shifted from Abney Mills to Burlington Domestics (soon to be Burlington Industries.) Manufacturing continued during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. At some point during this era, the towers on Mill No. 1 were shortened from 4 stories to 2 stories; although one explanation given for the shortening is that the workers felt the towers too "prison-like" I find this a doubtful impetus for the considerable expense. (During this same era, one of the two towers at Golden Belt was shortened as well.)

Mill No. 4 in 1977

(Courtesy Old West Durham)

Front gate of Mill No. 4, 1977

(Courtesy Old West Durham)

In 1986, Burlington shuttered the plants and sold them to the J.P. Stevens Co., and the factory closed shortly thereafter. Clay Hamner and Terry Sanford, Jr. purchased the property from JP Stevens. Having experience with adaptive reuse in Durham from their conversions of Brightleaf Square to retail and office space in 1982 and 500 North Duke St. in condominiums in 1984, they converted Mill No. 1 and the old office building into a combination of office and residential space. However, their adaptive reuse stopped there, as they demolished all other buildings associated with the mill, including the entirety of Mill No. 4

In 1988, they began construction of a 10 story 236,000 sf office tower with retail and office space extending to the north and west of the tower. It was slated to be the first of several such developments to be built on the then-vacant space once occupied by the mill as well as 10th, 11th, and 12th streets.

Construction of the office tower and associated retail space, 02.01.89. You can notice that the Durham Freeway empties into Erwin Road toward the right lower corner of the picture.

(Courtesy The Herald Sun)

The tower would house First Union and Wachovia, respectively, as anchor tenants. It was purchased for $38 million by SCI Real Estate from Durham developers Clay Hamner and Terry Sanford, Jr. in 1999.

Today, the Mill No.1 contains a mixture of apartments and offices - including quite a few Duke offices. The original office building also contain a number of office suites. The Erwin Square tower, I believe, is a general office tower at this point. Suites around the base contain a number of retailers and restaurants.

Erwin Mill No. 1, 04.12.09.

Erwin Mill office building, 04.12.09

Similar location to panorama of Mills No. 1 and No. 4, above, 04.12.09

Erwin Square, site of Erwin Mill No. 4, 06.13.09

While I'm happy that the Erwin Mills office building and the Mill No. 1 main building were preserved, I can't help but bemoan the loss of Mill No. 4 and all of the other associated buildings. The opportunity existed here to create something on the scale of the American Tobacco Campus. Admittedly, this would have been more challenging in 1989 than 10 years later, but given that part of the mill was preserved, I'm not sure why the entirety wasn't. Floorplates seen as too large? I don't know.

It's hard to get too excited about Erwin Square, that very-1980s new construction. Even if the "big field" is at some point developed, it's hard to imagine Erwin Square feeling very integrated with the rest of Ninth Street. To me, one feature says it all about the office tower/retail building - there is no sidewalk that connects the building to the sidewalk on West Main St. It feels like it got lost on the way to RTP/Cary/Glenwood Ave. to me. I know there are two Bakatsias restaurants over there, but I somehow always forget they, or anything else retail exists in that place - and I think that has a lot to do with the building and the site. Ah, what could have been.

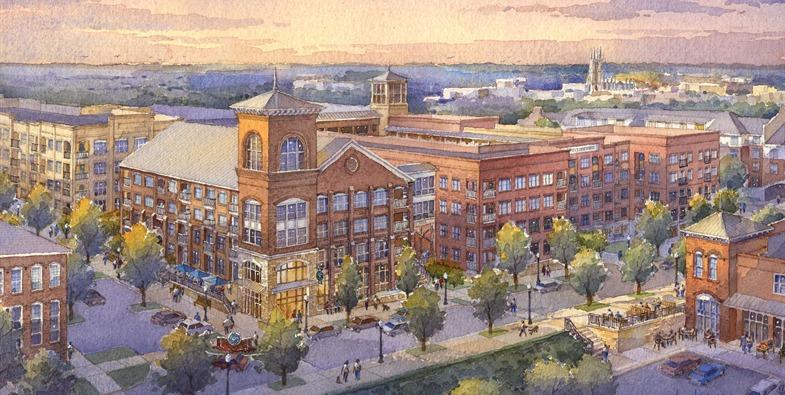

Update 2013:

As of 2013, Crescent Communities of Charlotte was developing a very large apartment / retail presence on land immediately to the west of Erwin Mill No. 2. I'm not a huge fan of the tower mimicry, and the god-awful suburban entryway that they've created off of 9th Street (to the Harris Teeter and the strip-center-resembling shops fronting the parking lot rather than 9th.) The apartment complex itself isn't bad, particularly from the western side, but the deviation from the original rendering, above, for the area to the north (I would guess they were bent to the suburban will of Harris-Teeter,) is terrible, and a lost opportunity to enhance the Ninth Street frontage (by double-siding it.) It also is a lost opportunity to truly connect the Station 9/Erwin Square stuff with Ninth Street. The gulf of parking and bad grading in between could have been avoided.

09.26.13

Comments

Submitted by Dave Piatt (not verified) on Wed, 6/24/2009 - 11:28am

Wow, what a post. Certainly worth the wait to read it. I often wondered about the field out there, now I know.

Submitted by Anonymous (not verified) on Wed, 6/24/2009 - 1:18pm

Yeah, too bad so much was lost. What a place that could have been in an incredible location. While this is now a great site for new development, there seems to be little effort at master planning the whole area to create a cohesive urban environment. Or, if there is, it doesn't seem to involve the community, other than getting the neighbors to give their input/blessing to individual projects as they arise (Station 9, planned hotel).

Submitted by John Schelp (not verified) on Wed, 6/24/2009 - 9:13pm

A stunning entry today, Gary. Absolutely stunning.

Submitted by Michael Bacon (not verified) on Wed, 6/24/2009 - 9:16pm

Gary, this was an epic post.

When talking about OWD to folks living in other parts of the city, it's frequently irritating to hear folks assume OWD has transformed into nothing but yuppies overnight. In fact, a huge proportion of the neighborhood, including three of my immediate neighbors, are former millworkers.

Anon: Sanford Jr. did in fact have a master plan for the entire area, but it went seriously wrong after the construction of the first tower. That tower quickly became some of the most expensive office space in the Triangle, and it became readily apparent that there wan't a market for a second equivalent tower. However, because the first tower is of that rate, building a second, similar tower on the other side of the big traffic circle (as was originally planned) would undercut the rents in the first tower, devaluing the same property. Hence, Sanford has essentially painted himself into a corner with the single building, and can't find a way out.

Station 9 and the hotel give him a way out on this. But yes, there was a plan. It just went awry.

Submitted by wren (not verified) on Wed, 6/24/2009 - 9:16pm

Take a bow, Gary.

That had to be a mountain of work. Great entry.

Submitted by John Schelp (not verified) on Wed, 6/24/2009 - 9:27pm

> seems to be little effort at master planning the whole area...

The Durham City Council unanimously passed the Ninth Street Plan in November 2008. This proactive effort covers the greater Ninth Street area -- between Broad Street (on the east) and 15th Street (on the west).

City Council members said they were inundated with messages from the community. Howard Clement said he received more emails on this topic than on any other issue during his time on Council.

These were tough and complicated negotiations. Thanks to people who care deeply about Durham, thanks to emails from the community, we were able to secure a much better plan for the Ninth Street area.

From the beginning, we sought a balance between protecting what's special about Ninth Street, while allowing more density nearby (such as the area near Erwin Square).

The measure includes the new building height limits and green space language raised by the neighborhoods, merchants and others. We also added text supporting public open space on Green Street, across from EK Powe.

Developers will have less of an incentive to tear down the shops and restaurants along the east side of Ninth Street (national register district). The new development across Ninth St will be more compatible in scale with the surrounding district (with denser development allowed nearby).

You can see the Ninth Street Plan here...

http://www.durhamnc.gov/departments/planning/pdf/ninth_street_plan.pdf

~John Schelp

Old West Durham

Submitted by John Schelp (not verified) on Wed, 6/24/2009 - 9:31pm

Council OKs plan for Ninth Street

Herald-Sun, 18 Nov 2008

City officials put the finishing touches on and approved a plan Monday for the Ninth Street area that will shape upcoming zoning and ordinance changes to support development there.

The plan got a unanimous City Council vote after landowner Terry Sanford Jr. and activists from the Watts Hospital-Hillandale and Old West Durham neighborhoods told members they'd agreed to a compromise on allowable building heights.

The deal emerged from a negotiation that "did have its arduous moments here and there," Sanford said before the vote.

As rewritten Monday by city/county planners to reflect the deal, the plan calls for zoning the Ninth Street corridor in a way that would allow buildings on the west side of the commercial strip to stand up to 55 feet tall.

Sanford owns most of the property on the west side. He said in August he'd need more height than a draft the council looked at that month would have allowed, if he was to make the sort of transit-friendly development the city wants there pay.

Neighbors secured from him agreement to language that's supposed to force builders to vary the façade of any development.

The plan calls for changing setbacks and roofline every 50 feet to break up the apparent mass of new buildings. It also favors having developers include "stepbacks" in their designs, meaning they'd pull the upper floors of their buildings a little farther from the street than the lower floors.

Most critical to the neighbors, however, was Sanford's concession that at least half of the street frontage of west-side buildings should stand three stories tall or less.

Buildings on the east side of Ninth could reach up to 40 feet, but the plan calls for a mix of one- and two-story structures.

The two sides in the talks battled back and forth until last Friday, when Old West Durham Neighborhood Association President John Schelp e-mailed council members to say they'd made a deal [on building heights; Sanford didn't agree to the open space language until yesterday afternoon -- JS].

Sanford last Tuesday signaled that he was amenable to a 50-50 split of three- and four-story buildings. Schelp's e-mail, however, included the wording that planners actually incorporated into the document.

Over the weekend residents of the two neighborhoods sent council members dozens of e-mails urging them to avoid tinkering with the deal.

Neighborhood leaders made the point again Monday night, calling the terms "a community compromise."

The agreement "protects what's special about Ninth Street and, at the same time, address concerns raised by the development community," Schelp said.

Click here to see the 9th Street Plan...

http://www.durhamnc.gov/departments/planning/pdf/ninth_street_plan.pdf

Submitted by David E. Jeffreys (not verified) on Thu, 6/25/2009 - 1:41am

I agree with the others, that you, Gary, even outdid yourself on this historical post. Even though I went to E.K. Powe school in the 1950s, I never knew who he was until I read this post. I would like to find out even more about him. He must have been influential to have the school named after him.

The one thing I cannot seem to figure out though is any relationship of the mill to the railroad. Though the main mill campus is on one side of the North Carolina Railroad tracks and Erwin Auditorium is on the other, I have never seen any railroad sidings that would have made it possible for loading boxcars with goods for shipment. Did Erwin Mills ever use the railroad or did they get their products to markets through other methods such as trucking?

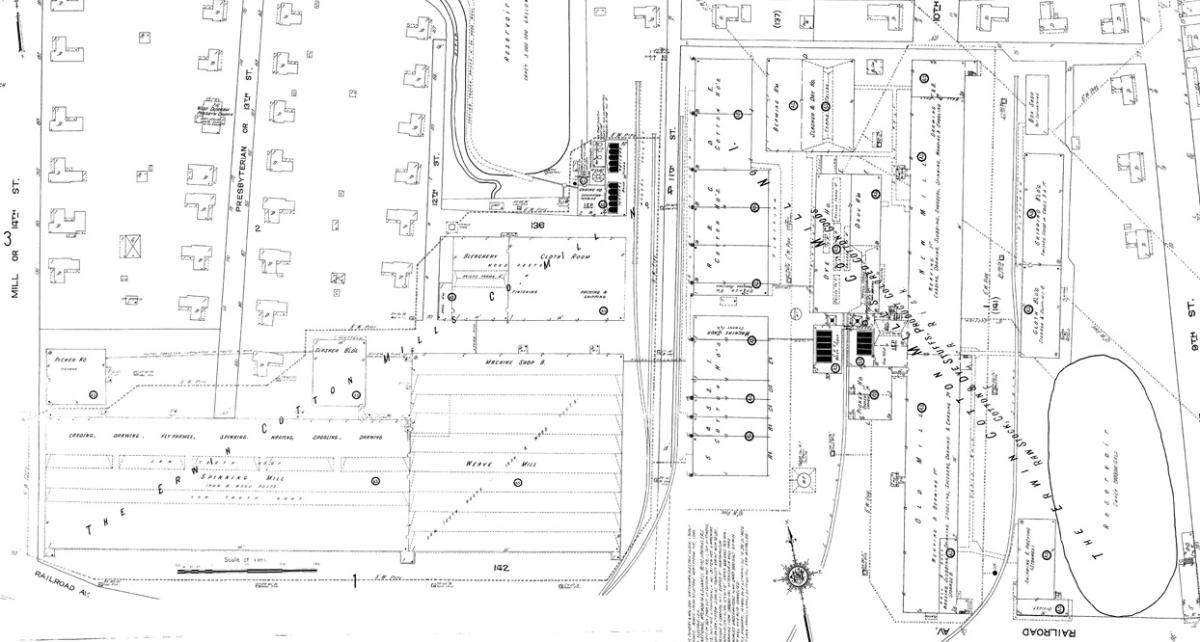

Submitted by Gary (not verified) on Thu, 6/25/2009 - 2:31am

Thanks all. This one did take me awhile.

David, if you look at the black and white Sanborn map ?6 pictures down, you can see the ~5 railroad sidings curving off of the main track and extending to the north, in front and behind the warehouse and mill buildings. (The main line isn't pictured on the map, but it would run horizontally at the bottom of the map.) You can also see one of these splitting off from the main track in the picture taken from Erwin Auditorium, looking toward Mill 4 past the line of people.

I assume the last of these was probably taken up / paved over in the 1950s, but I'm not sure when they went out of use.

GK

Submitted by Anonymous (not verified) on Thu, 6/25/2009 - 12:39pm

Thanks John. I was talking about master planning by the developer, Terry Sanford, Jr. on the large field between Station 9 and the remaining mill. Development on that land seems to be somewhat hodge-podge. I know a lot of hard work went into the 9th Street plan. Michael, thanks for the info on his old master plan. Perhaps it is time for Sanford to update his plan.

Submitted by John Martin (not verified) on Thu, 6/25/2009 - 1:14pm

As everyone else has said, this is an absolutely fantastic post. But because I'm old-fashioned, it makes me yearn to see all of this between hard covers. Have you ever thought about trying to interest a publisher in an "Architectural History of Durham?" You've got a lot of it written already, and it would be a wonderful book.

Submitted by Todd T (not verified) on Thu, 6/25/2009 - 7:32pm

Thanks Gary. Absolutely awesome.

I love the birds eye photos (as always) especially the one facing SW in the 30's.

Submitted by John Schelp (not verified) on Thu, 6/25/2009 - 10:54pm

Couple of more comments...

* Here's the 1920 Wells & Brinkley street map of Durham that shows RR tracks going into Erwin Mills... http://www.owdna.org/1920map.htm

* Thanks for your note, Anon. The Ninth Street Plan echoes what the property owners envision for Erwin Square -- all the way down to the open space along Green Street (across from EK Powe). ;)

* Edward Knox Powe's portrait still hangs in the lobby of EK Powe. The Center for Documentary Studies ran a wonderful Neighborhoods Project at the school that included a week focused on Old West Durham. Working as "neighborhood detectives," 2nd graders went on a field trip into the neighborhood.

On one walk, we bumped into six people working in their yards (between the ages of 30 and 80). All six had attended EK Powe. Another day we brought the students to the porch of a mill house for cookies and juice. The students were completely surprised to meet EK Powe III!

See photo in the middle of this page... http://www.owdna.org/news2.htm

Submitted by Gary (not verified) on Sun, 6/28/2009 - 3:47am

John M.

I've had some interest from publishers about doing a book; it certainly intrigues me. I just don't think I can continue to write the website and write a book. While I have a lot of info, it's figuring out how to reduce it to something that would fit in a book, layout, etc.

GK

Submitted by kwix (not verified) on Mon, 11/2/2009 - 3:42am

Not many weeks after my wife and I moved to Durham for grad school in the mid-80s, we heard that the Burlington Mills factories between Main and Hillsborough were shutting down, and having a big sale to get rid of excess inventory of household textiles.

We stopped by to see what bargains we poor grad students might find. As I recall, we entered into one end of an ENORMOUS building, and the sale items -- although vast -- occupied only one corner of the building. I think we got some towels and sheets.

Everyone there was very aware at the time that this was Durham's last link to its textile/industrial past (the tobacco factories & warehouses I think had already shut down or moved away) -- and that Durham's future now lay in some other, probably high tech, direction.

Submitted by Dale Gore (not verified) on Mon, 8/5/2013 - 10:35am

Those pictures bring back great memories. My Dad, Ralph Gore worked there for 45 year, and my Mom worked there until she took a job helping run their union. My brother and I both played for the baseball team UTWA Local 257. Thanks for the pics.

Submitted by Janice Camden (not verified) on Tue, 1/7/2014 - 8:02pm

My parents, Fred and Sallie Lane both worked 3rd shift at this mill for several years. Neither one of my parents had more than a 3rd grade education but were hard working people. I remember both of them being tired and sleepy all of the time. My Father retired due to health reasons, I think it was about 1960. My Mom continued working at the mill until 1962. Both of my parents wanted their children to get a good education and not work in a cotton mill.

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.