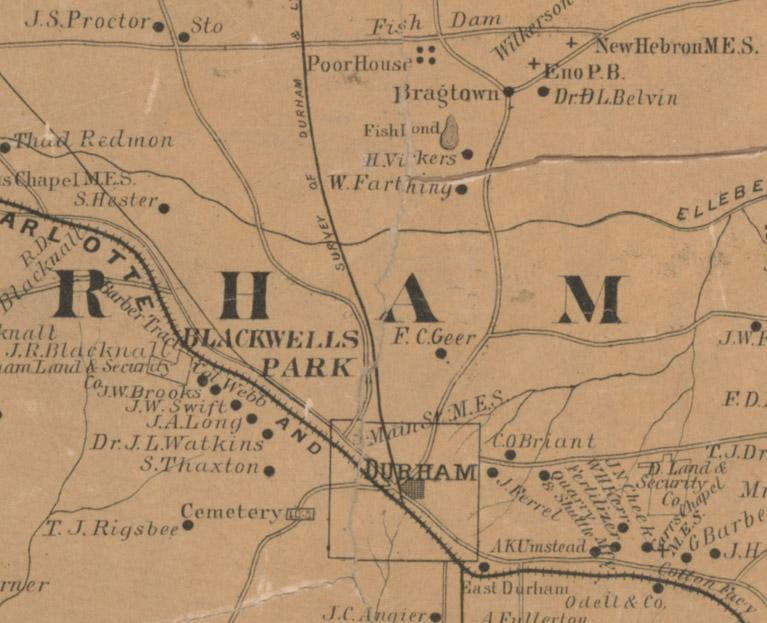

1890 Map showing Blackwell's Park

The land that would become the Durham site of Trinity College, later East Campus of Duke University, is first noted in Durham history as a horse racing track and occasional fairgrounds, known as Blackwell's Park. The 67.5 acres was acquired by James W. Blackwell in 1880-1 from Archibald Nichols and developed as a racetrack. By 1886, JW Blackwell had given up ownership to his brother WT Blackwell, of Blackwell's Bull Durham Tobacco Company. Blackwell was bankrupt by 1888 due to the failure of his Bank of Durham; whether he sold it to Julian Carr or Carr took the land as payment for debt is unknown.

The Park was described by the News and Observer in 1890:

"The Blackwell Park at Durham, where Trinity College will be located, is one of the finest pieces of property in the State. I had no idea what a magnificent site and fine grounds the college had until Brother B.N. Duke took me over them. There is 62 1/2 acres upon which $40,000 has been expended in improvements of various kinds. There are a number of neat cottages scattered around over the grounds, four fine wells of water, a large building used as a grandstand, and a fine drive made for a track to try the speed of horses, and within this circle is the finest grounds for athletic sports to be found anywhere. There is a fine orchard on the grounds, and grape vineyard, a large stable (two of them), and a hennery. In fact, there is every appliance for a truck and dairy farm. Then there is a grove of young oaks, large enough to make an excellent shade, on another part of the grounds."

In the 'Carr-washing' of Duke and Durham that seems a progressive trend in the popular history of our city (i.e. "Durham: A Self-Portrait",) Carr's role in bringing Trinity College to Durham has sometimes been minimized or forgotten.

Carr had become a financial supporter of Randolph County's struggling Trinity College a few years prior to the point at which he acquired Blackwell Park; he began supporting the college with two other trustees ( 1855 Trinity Alumnus and banker Colonel John Wesley Alspaugh and James A. Gray, another Winston-Salem banker) in 1885. In 1887 he gave the college $10,000 in securities as an endowment to keep it afloat. His initial association with the college seems to have come about through the rather incredible story of his relationship with Soong Yao-ju, otherwise known as 'Charlie Soon'. That story deserves its own telling on this site, but not here. After becoming Soong's patron, and paying his way to Trinity, Carr seems to have increased his support of the struggling college.

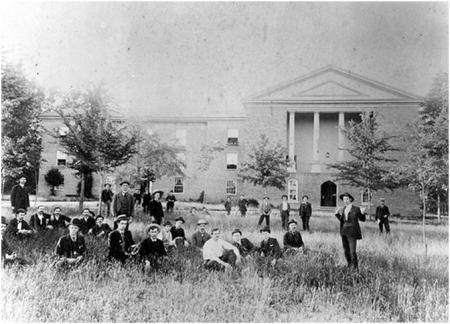

Trinity College had arisen from Brown's Schoolhouse, a small 16 x 20 ft log cabin in Randolph County, established around 1830. Brantley York, a Methodist preacher, became head of the schoolhouse in 1837. He moved the school to a new, larger building "some distance from the old [one]." In 1840, the school was enlarged and renamed the Union Institute, and in 1841, it incorporated and became the Union Institute Academy. It became well known under the leadership of Braxton Craven, who headed the school after 1842, and a town, named Trinity, NC, grew around the school. In 1851, the Union Institute Academy was incorporated as Normal College, a state teachers' college. In 1853, the college received funding from the state and was empowered to grant other, more general, college degrees. Curricula included "preparatory, classical collegiate, and English."

In 1855, a single, all-purpose brick masonry structure was built to house the college, and the next year the school was 'adopted' by the Methodists. The college no longer focused on teacher education and expanded its liberal arts curriculum. One of the trustees, R. T. Heflin, suggested that the college’s name be changed to Caswell, in honor of Governor Richard Caswell, a Revolutionary War hero and devout Methodist. However, when the charter was amended in 1859, the institution changed its name to Trinity College, in honor of the institution in Cambridge, England. Braxton Craven was named first president of Trinity. The school briefly closed its doors in 1864, under occupation by Union troops, but Craven returned to re-open the school in January 1866. The main building was expanded between 1872-1874 with a wing that fronting the road which is now NC62. The new wing set at a cross-angle to the 1855, forming a T. The new wing contained classrooms and a chapel.

Trinity College, Trinity, NC.

Craven remained president of the school until his death in November 1882.

See the original site of Trinity College in Trinity, NC on a Google Map

Carr became chairman of the search committee seeking a new president for the college, and played a strong role in the eventual choice of John Franklin Crowell. Although Crowell's northern heritage and Yale degree would seem at odds with Carr's southern proclivity and the situation of the college, Carr had high aspirations for the institution, and Crowell came highly recommended by Carr's good friend at the University of North Carolina, Horace Williams, despite the fact that Crowell was only 29. (Williams and Crowell were classmates at Yale.) Although the secondary sources suggest that Carr was initially against Crowell's later desire to move the school to a more urban location, I rather doubt that the savvy Carr didn't foresee this.

The Methodist Conference agreed at its 1887 convention to endorse relocation of the college. They concluded that the cost of the move, new site, and erection of a new building would be $20,500.

Crowell began to solicit interest from various North Carolina cities; Raleigh offered the school $35,000 for the move to a location currently occupied by NC State, and the Methodist Conference approved the move to Raleigh.

Durham - having lost the Baptist's Female Seminary (later Meredith College) to Raleigh despite offering more money - and wounded by the disdain with which the Seminary and Baptists had regarded "pushy little" Durham, calling it "no fit place for innocent girls to abide in" - would not go easily into the good night. The story of how Carr and the Dukes came together to bring Trinity to Durham seems to vary in every account, but clearly the tobacco rivals either saw this as an important opportunity which transcended their competition, or neither wanted to be outdone by the other - or both.

The one thing the Carr and the Dukes had in common was that they were easily the most prominent, and richest, Methodists in Durham (if not a much larger geographic area.) Robert Bumpas, minister of the Main Street Methodist Church, built by the Dukes, and EA Yates, presiding elder of the Durham District of the Methodist Conference, implored the Washington Duke to intervene on Durham's behalf.

Jean Anderson, quotes Bumpas' recollection, written to Ben Duke in 1898:

"I have thought of the day I went to your house after dinner and found you lying on the lounge in the hall, and you told me you were thinking of buying [Blackwell] Park and building an orphanage for the Methodist Church [on the site]. When I suggested that you have Trinity College moved to Durham, you agreed to consider the matter."

Per the Duke Archives and Robert Durden:

When Washington Duke's former pastor and then District Superintendent E. A. Yates told Duke of Raleigh's offer Duke casually remarked that Durham could match that and add $50,000 for endowment. Yates inquired if he could wire Crowell such an offer and immediately the college president was in Durham personally meeting Washington Duke for the first time. With a pledge from Duke of $85,000 in hand, Yates and Crowell hurried across town to ask their friend Julian S. Carr, long-time trustee and the largest benefactor of the college to date, if he would donate as a site the fair ground he owned on the western edge of the city. Carr agreed without hesitation, conveying to Washington Duke, 'I shall ever feel proud to point to you as a fellow townsman..."

When called to meet in Durham on March 20, 1890, the trustees accepted the offers from Duke and Carr with gratitude. The formal offer from Duke was signed by Washington but written by Benjamin. As further inducement, citizens from Durham presented a check for $9,361 for endowment and the trustees enthusiastically proclaimed that with Duke's gift for endowment and a building, funds were ample for a solid beginning. Upon request a committee from Raleigh relinquished its claim and the Christian Advocate, the official organ of the church, proclaimed, 'All Methodists could write the address Trinity College, Durham, North Carolina with pride.'

Crowell referred to the move as "placing the college upon the highway to success in the service of humanity."

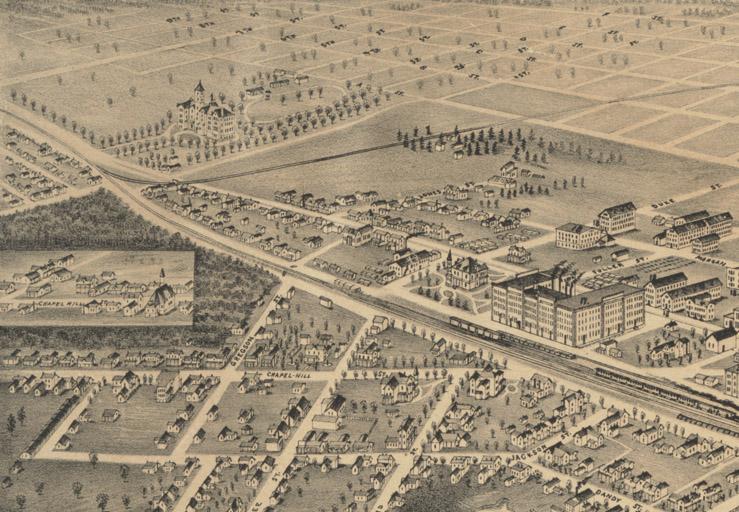

Planning soon began to erect buildings on the former park and racetrack. Washington Duke headed the building committee, but Ben Duke bore most of the responsibility for his aging father. The original campus consisted of three campus buildings: the College (Main Building,) College Inn, and the Technological Building, which also contained the generator for the campus. The college also constructed five houses for professors just to the south of the College Inn, collectively known as Faculty Row. Some accounts refer to a sixth house on campus that was existing and renovated - this may have been the Edwards/Robertson house (who lived in the house or what its use was earlier is not clear.)

When the Main Building was near completion in August 1891, the central tower collapsed The building needed to be rebuilt, and Trinity's move to Durham was delayed for a year.

Finally, on October 12, 1892, the opening of the college occurred:

"Trinity dedication will take place on Wednesday, October 12. The first feature of the day's program, set for 10 o' clock at Main Street Methodist Church will be the dedicatory sermon by Dr. E.E. Hass of the Christian Advocate, Nashville, Tenn. At 2:30 pm, a procession of municipal authorities and civic and military organizations will be formed in front of the post office and march to the main entrance to Trinity Park. [Changes in plans were made which appeared in a later Issue of the newspaper. The courthouse was named as the point for the formation of the procession and J .S. Burch was announced as the chief marshal.]

"On arrival at Trinity Park, the procession will be met by the trustees, faculty and students of the college. An address of welcome to the college will be delivered by Capt. E.J. Parrish on behalf of the mayor (M.A. Angier) and the people of Durham. This will be responded to by President Crowell, on the topic 'The Relation of the College to the Life of the People.' A formal transfer of the buildings and grounds to the board of trustees will be In the following order.

The main college and Inn by Washington Duke.

Trinity Park by J.S. Carr.

The technological building by President Crowell.

The furniture by Dr. F.L. Reid.

The dedicatory address by Rev. Dr. E.A. Yates.

Prayer by John R. Brooks.

Doxology.

Benedictation

All school authorities and the schools of the town are expected to participate. All benevolent organizations are invited to attend."

The Issue of the Globe three days later reported that "Everything at the college Is being put into readiness for the dedication Wednesday. Dr. E.L.. Reid, who did so much towards raising, money to furnish the several buildings spent two days here this week and the result is two elegantly appointed parlors, one In the main building and the other the college inn, parlors In keeping with the handsome exteriors and such as great institutions, like new Trinity, must have In order to compete. "The furniture in the former was donated by Messrs. Hanes brothers of Winston in memory of their father who lived In Davie County. It is a beautiful room and a fitting memorial of a good man. The fitting of the latter was made possible through the generosity of friends of Dr. Reid, and also a memorial room, it being in the memorial of Dr. Reid's, father, Rev. N.F. Reid.

Trinity opened its doors in Durham in the Fall of 1892 with an enrollment of 180 men, budgeted expenses were $17,900 for the year, and anticipated tuition revenue of $4500, with $2300 still owed from the previous term. The Dukes supported the college, and became increasingly angry at the lack of financial support for the college from their fellow Methodists of NC. They supplied $7500 a year for the first three years if the college could raise an additional $15,000 per year.

While this would not be the end of the financial strain for the college, it allowed Trinity College, Durham to stay open during its first semester with some relief of the pressure of meeting its obligations.

1891 Bird's Eye from downtown, showing the main buildings of Trinity College and a smattering of small frame structures.

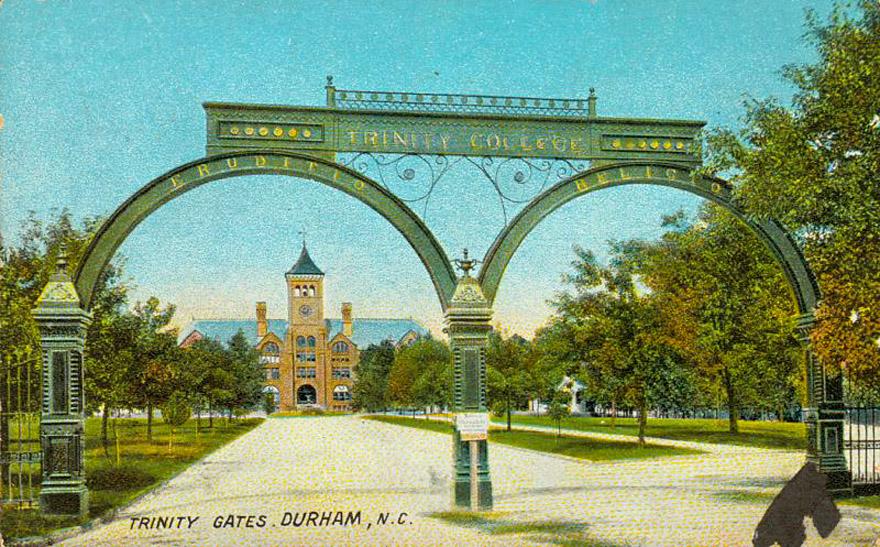

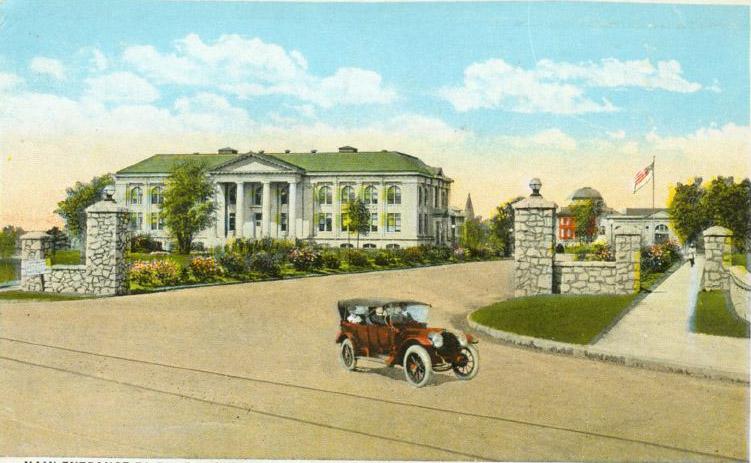

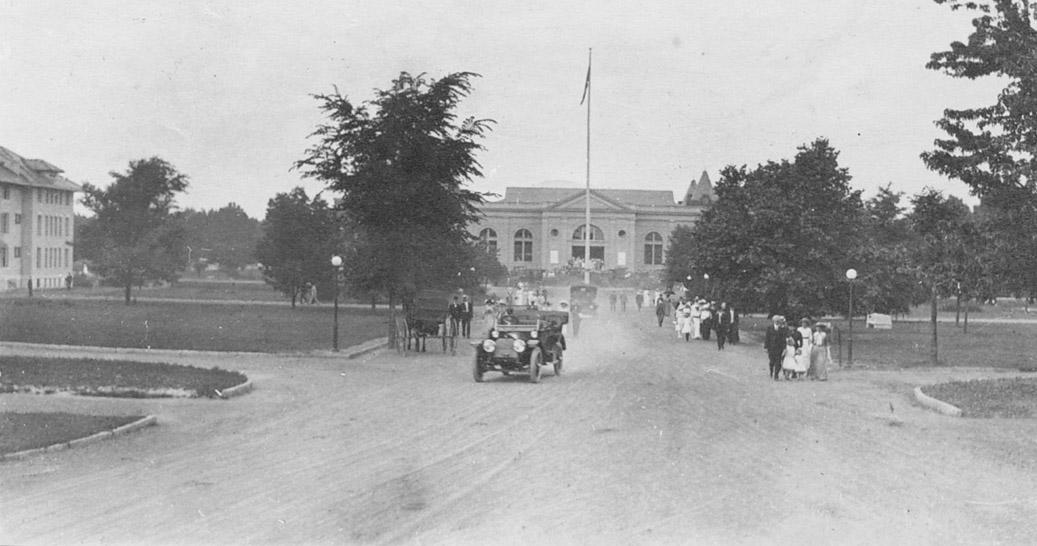

The main entrance of the college was located on the south side of the former park, on West Main St. A set of iron archways framed the entrance, with the vista terminated by the Main Building, later known as Old Main/the Washington Duke Building.

Trinity College entrance, looking north from West Main, 1904.

Trinity College entrance, looking north from West Main, 1904.

Location of the original entrance to Trinity College in Durham, 08.16.10

Back in Randolph County, the old college buildings were turned into a private college preparatory school, which became a public school in the early 20th century. In 1924 a special school tax district was established in Trinity and a new elementary school and high school building was built on the site of the college. That was in turn torn down in 1981, and the historic site is now a parking lot. The only remnants of the college - a gazebo and school bell are squeezed between NC 62 and the fence around the lot.

* * *

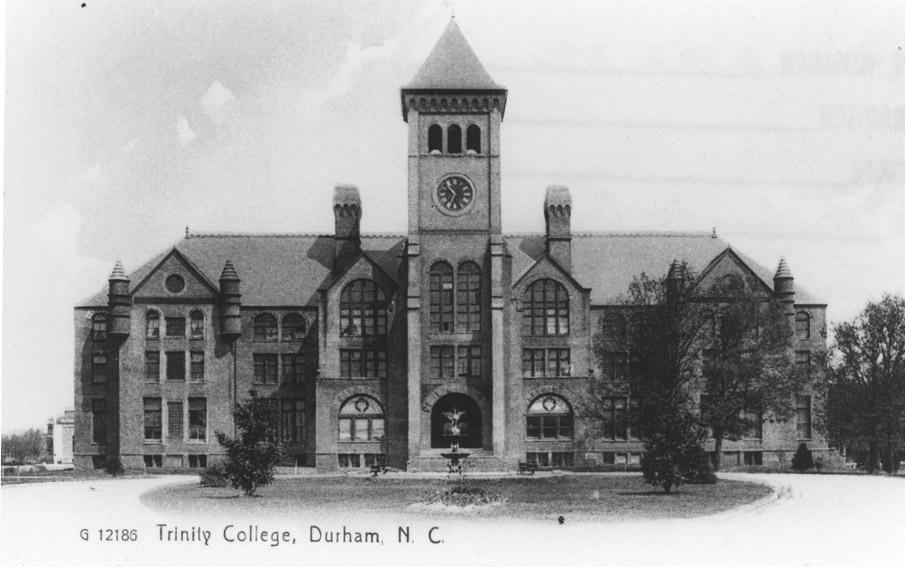

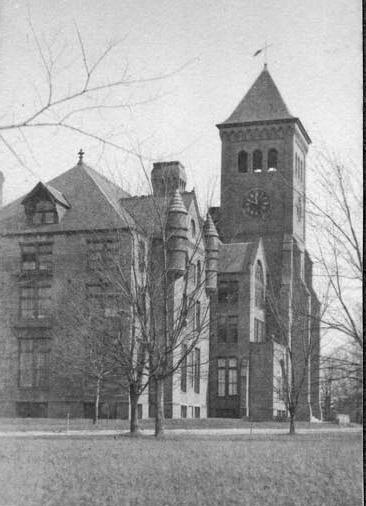

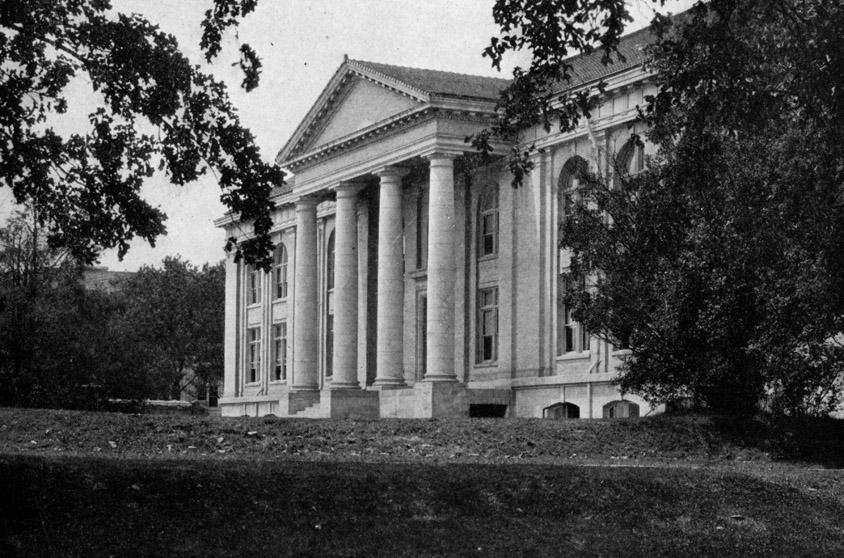

The College / Main Building / Washington Duke Building / 'Old Main'

Built: 1890-1892

Architect: Samuel L. Leary

Status: Destroyed by fire, January 1911

Samuel L. Leary was chosen to design the Main Building of the Trinity College Campus, later known as 'Old Main' or the Washington Duke Building. Leary, originally from Philadelphia, was one of Durham's early prominent architects, responsible for the design of St. Joseph's AME, the original Fire Station #1, the First (white) Graded School (later Morehead School), and the Foushee House (now Camelot Academy on Proctor St,) and his own house, the Leary-Coletta House on Cleveland St. Leary is also rumored to have designed the classic Durham form of the tobacco warehouse, first demonstrated by the Walker warehouse, but this is unsubstantiated.

CH Norton, who had built the Durham County Courthouse and the Fuller School was chosen as the contractor. The design was a 50 foot by 208 foot building with 12 lecture rooms, offices and labs on the 1st floor and in the basement and 60 dormitory rooms on the 2nd and 3rd floors. A clock tower was to extend an additional story over the front facade. The cornerstone was placed on November 3, 1890.

The building was to be completed for the beginning of the Fall Term, 1891. Concern mounted about the rapid schedule, and Crowell issued a statement to allay fears that the clock tower was unsafe. Exactly one week later, the clock tower of the nearly completed building collapsed, destroying 2/3 of the facade, the roof of the building, and the tower itself. The design was evaluated by WJ Hicks, a Richmond architect who had designed the Gothic Central Prison in Raleigh. He found defective masonry, and that the sides of the base of the archway below the tower were insufficiently buttressed to support the weight of the tower. Hicks replaced Leary as architect and Norton stayed on as contractor.

Although the historic inventory points out that Leary designed the Foushee house and St. Joseph's AME after this incident, there seems little doubt that this harmed his reputation, as - those commissions aside - Leary seems to fall off the face of the planet by the turn of the century.

The building was completed for the Fall semester of 1892, and the college moved to Durham.

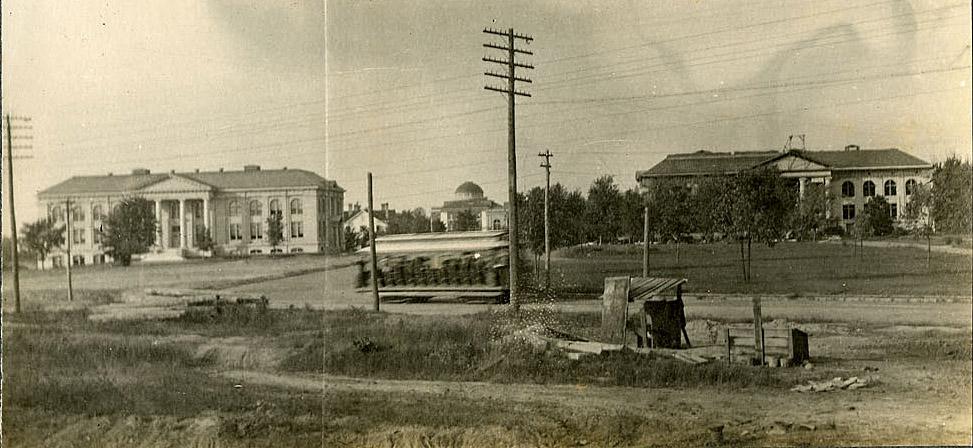

Looking east, 1890s.

Rear of the building, looking south, 1909

The Main Building was renamed the Washington Duke building after his death. It was the center of academic life for the college, as recollected by Gilbert Rowe in 1915:

"The old Washington Duke Building stood for 19 years and came to a spectacular end by fire. It had, however, served its generation and was about to be removed to make way for the larger building which now occupies a part of the site. This building began to affect the life of the college even before it was occupied, for it was the falling of the uncompleted tower that delayed the removal of the college for a year.

As I remember my college days, I am spared the conflicting emotions of many other students, because my life as a Trinity man began with the history of the college in Durham, In 1892 late in the afternoon of the day before the new college was to open, a crowd of students landed upon the campus. Although my roommate and I had acted upon the advice of the authorities and reserved a room early in the summer, we were unable to find out where that room was and were quartered for the night in the old Inn. As I lay upon the bed that night and looked first upon the bare walls and then out upon the campus, dotted with scrubby oaks and lettered with scantlings and piles of plaster. Little did I think that this campus finally would begin to feel more like a home than any other place, or that it would ever assume the beautiful aspect that it presents today.

The next day we learned that we had been assigned number eleven in the Duke Building, All the dormitories in this building were built upon one of two plans. Some of them were small, while others were more commodious and had a sleeping apartment cut off by a low partition. During my entire course I remained upon the second floor, although I changed rooms several times. All of the rooms were comfortable and substantially furnished; but although bowls and pitchers were provided, most of us preferred to repair early in the morning to the common bathroom where we could splash at will. The heating arrangement was the source of greatest annoyance. In extremely cold weather all the heat went to the south side of the building, and when the south wind blew, those on the south side roasted.

The Duke building was a long rectangular structure built of red brick. On the top and toward the front was the tower with its large, sweet-toned bell, which not only struck the hours, but served as a bell by which the janitor announced the engagements of the day. The day began with the rising bell.

The Duke Building was at the time the most important upon the campus, the only important public events taking place elsewhere being meals and chapel exercises in the Inn. It contained the president's office, the library, the society halls, a parlor. and practically all the recitation rooms, as well as dormitories lor about half the student body.

Life in this building was made up of some study, some amusement. and a great deal of social conversation. Practically all of the students gave some attention to books and recitations, though doubtless when they learned that the records had perished in the burning building, many found it difficult to lament over the loss."

By the latter part of the first decade of the 20th century, the college had already outgrown the building, and plans were developed to replace the building. Before that could happen, the building burned on January 4, 1911.

Looking north, with the Anne Roney Fountain in the foreground.

Ruins of the Washington Duke Building, from a postcard, looking northeast.

Looking southeast, 1911.

The building was torn down soon thereafter, and the East Duke Building was built close to its original footprint.

Location of Washington Duke Building / Old Main

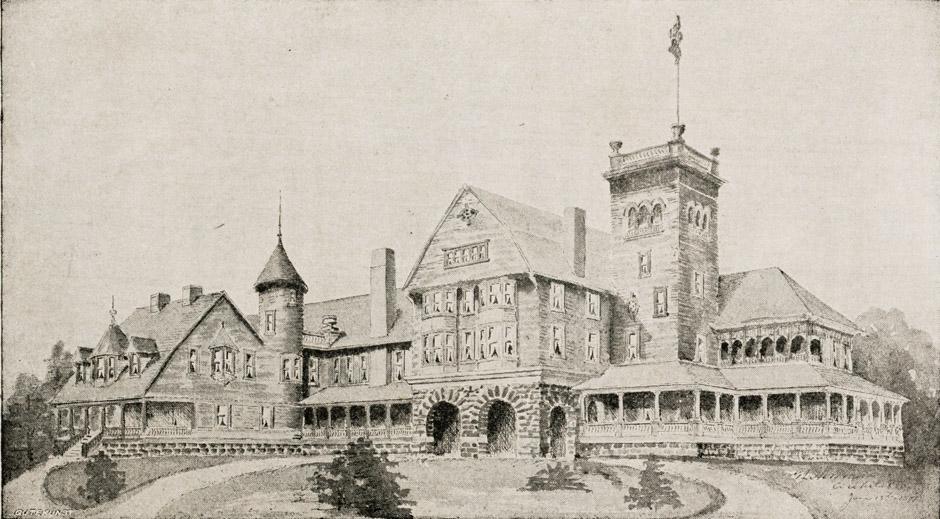

College Inn / Epworth Inn

Built: 1890-1892

Architect: Unknown Architect from Washington, DC

Status: Partially torn down during 1914; western portion remains standing.

The College Inn was built between 1890 and 1892 with a $30,000 gift from Washington Duke. A large, rambling Shingle Style structure, the building was a center for social activity at the college, a dormitory, and hotel. The first floor contained a dining hall, parlor, chapel, and guest rooms. The second and third floors contained 75 dormitory rooms. Board was $10 a month at the dining hall. An on-site dynamo provided electricity sufficient to provide a light bulb in every dormitory room - more than the vast majority of the city of Durham could claim at the time.

Epworth rendering (labelled "Trinity Inn") 1895

Wyatt Dixon wrote a recollection of Epworth in the 1930s which gives a sense of life in the all-purpose building.

The Inn, as it is known today, is only one wing of the structure which once covered nearly half an acre [...]. In its original state, the Inn's gables, dormers, towers, arcades, and porches projected in all directions. It was built in the style of an old English tavern. The building has been the subject of admiration from visiting architects. Even though a large part of the building was destroyed by fire, it continues to attract attention.

One wing of the destroyed portion of the building was known as Cat’s Head and housed many generations of Trinity alumni. It is said that a group of students known as the "Dirty Dozen" occupied the wing. They so terrorized the freshmen and scandalized the dean that they were dubbed "the cats." For two years the building was not used as a dormitory. In the summer of 1914 it was remodeled when the eastern portion of the building, three stories high, was torn down, including the tower.

Epworth Inn was constructed at a cost of $31.679 and was the gift of Washington Duke, who gave many thousands of dollars to the college. The dining room had a seating capacity of 250 persons in its original state, but in 1914 the 75 bedrooms were reduced to 45 rooms. An old alumnus wrote in his memories of the inn that "at the very mention (of its name) there leaps out of the past the sound of a thousand hearty voices . . . and a thousand hands reach to me across the span of a seeming age,"

Dr. H. E. Spence, in his book "I Remember," gives an excellent description of the building as it was in its original state. "Closely rivaling the main building in importance was the Epworth Building, commonly known as the Inn," he writes. "Here was located the only public dining room managed under college auspices. The building was four stories high. On the first floor was the YMCA hall, a spacious room accommodating a couple of hundred students. Here public debates, religious exercises of all sorts, class meetings, and other public gatherings were held. Some dormitory room was available on the first floor. The majority of the rooms, however, were on the second and third floors. Fantastic names were given the various sections of the building. Among these were Ragged Row, Wall Street, and an alley whose qualifying adjective is unprintable. The fourth story consisted of one lone room - a fraternity initiation room. Just before its mysterious door was reached, there was a long circuitous stairway opening out of nothing but a four-story drop. The candidates were reminded of this as they entered the hall. A part of the initiation consisted of blindfolding the candidate, bringing him to where he could feel the edges of these open arches and then throwing him downstairs. Of course, he was thrown down these steps instead of out the window, but the thrill of the 10 or 15 foot drop before he hit the blanket, held by waiting students, was a rather graphic experience. "

According to Dr. Spence, the first floor contained a lounging room where many students met after supper to engage in some spirited bull sessions. Here was formed what he described as the most unusual organization he has ever known. One night a group of students were sitting in the room when a student walked in. Without previous arrangement, the men sat silent for a moment, then broke into loud and prolonged laughter. The student looked puzzled. The more puzzled he looked, the louder was the laughter. In this fashion the Damn Fools Laughing Association was formed. The lounge became one of the most popular gathering places on the campus. When a new student came into the group. every man in the the room would laugh as though he was looking at the most ridiculous spectacle they had ever seen. If the student couldn't stand the treatment, he left and didn't come back.

The first floor also contained a large dining hall, parlors, barber shop, shoe and candy shops, cold drink and tobacco concession, and a clothes presser. Chapel exercises and commencement were held in the dining hall until Craven Memorial Hall was erected.

Epworth, looking east-northeast, 1909

Epworth, looking north from Faculty Row, 1909

... and another, equally colorful description from an alumnus

"Memory of the Old Inn" is the topic of a story about Epworth Inn written by C. R. Warren of the class of 1906 of Trinity College which appeared in the first issue of the Trinity Alumni Register. [It reads, in part,] ‘One of the first buildings erected on the new campus in Durham was the Inn, afterwards named Epworth Building. This was a building of great beauty from the standpoint of architecture. Here lived the majority of students for many years, and around this dormitory have centered some of the most cherished memories and traditions of generations of Trinity men.

This was the center of the activities of college life. On the first floor were the large dining hall, YMCA hall, and parlors. Chapel exercises were held here, and until Craven Memorial Hall was built the commencement exercises were conducted in the large dining hall. On the verandas of the Inn students were accustomed to gather, sing their college songs, and discuss questions in which they were interested.

The time came when extensive repairs must be made to the building, and for two years it was not used as a dormitory. It was decided last summer to overhaul the building and thoroughly remodel it. The eastern portion of the building, which was three stories high, was torn down together with the large tower. The portion preserved was covered with slate. plasticoed on the outside, replastered, repainted and refloored. The building bas been divided into two sections and has been furnished with all modern conveniences. Shower baths have been provided for each section and running water for each room.

I shall never forget the impression made upon my mind when I first had the pleasure of looking the old inn over. I mean a part of it. I do not think there was ever a man who really knew every turn and corner of it. It covered nearly an acre of ground and faced to all points of the compass except north. It had a roof which from above looked like most anything you might think of that had no special shape or outline. I cannot describe it, for I am not sure that I ever saw it all. The halls, alleys, winding stairs. and various passages formed such a labyrinth of intricate turnings and twistings that truly one, on entering, must leave a skein of thread in order to get out.

The old inn had some rooms. It was like the widow's meal barrel and oil can. It never was full to my knowledge. It was the home of the freshmen. Almost every freshman that came to Trinity landed at the old inn for at least half of his first year.

The old inn was an entire institution within itself. There was a chapel, dormitory rooms galore, a library room, offices, recitation rooms, kitchen with basement and storage and a large dining room.

When I was there, the college had been making wonderful strides, and the recitation rooms had been converted into dormitory rooms. It was in one of them that I spent two of the happiest years of my life. A large porch ran about half way around the entire structure and there were two entrances.

It was in the old inn that Zack Beachboard had his boarding house and starved us all while he got rich. It was here that Warren had his barbershop and chopped the hair and faces of his trusting victims. It was here that Joe Pitts had his Regal Shoe Agency and took our money while he made us wait for the shoes. Here Aiken bad his candy. pop, chewing gum. and tobacco joint, and would not sell us his poison on credit. Here Zalph Rochelle had his pressing club and burned up our clothes, but didn't care: it was college and we were there.’

Epworth, ~1910.

In 1896, the name of the building was changed to the Epworth Inn, using the name of the parish where John Wesley'sfather was minister in England.

By the 1910s, the Inn had fallen into disrepair, and fire had damaged a portion of the building, In 1914, the eastern 2/3 of the building was demolished. The remainder was remodeled; the shingles were removed and the exterior stuccoed.

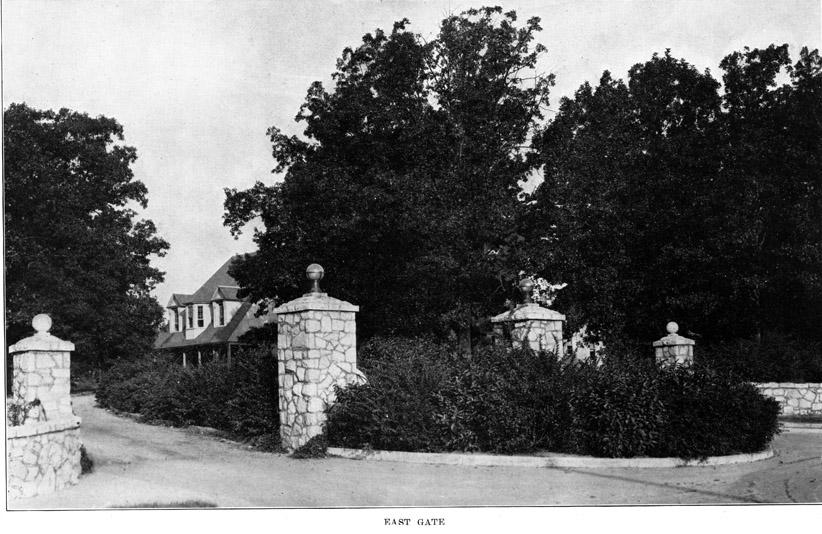

Epworth from the "East Gate" - 1920s

While the structure has been remodeled multiple times in the interim, it remains a dormitory.

Looking northwest, 10.21.09

Looking northeast, 08.25.10

Location of the College / Trinity / Epworth Inn

Technological Building / Crowell Science Building / Crowell Hall

Built: 1890-1892

Architect: Unknown, but construction supervised by Richard Baxter Bassett

Status: Standing as of August 2010

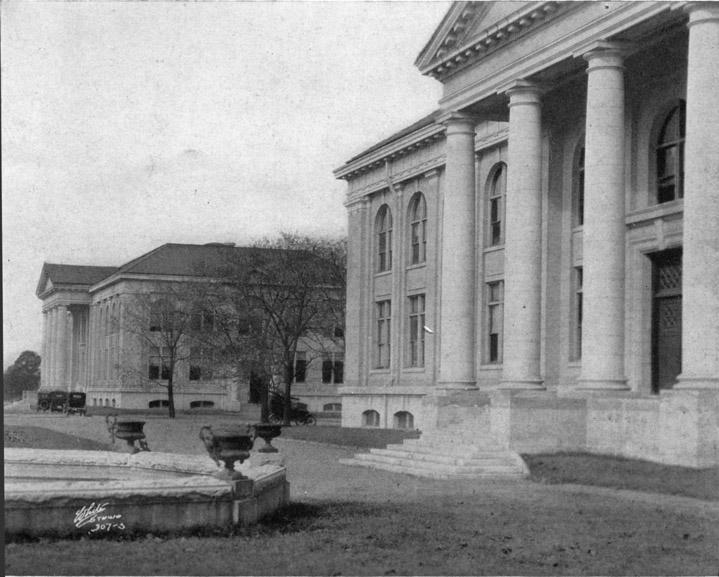

Crowell Building in the foreground, 1904.

One of two buildings built during the initial construction of the Trinity College campus that remains standing in its original location, the Crowell Building was initially called the "Technological Building" because it housed the School of Technology. The building housed drafting rooms, and laboratories for chemistry, physics, and biology. The main generator for the campus was housed in the basement. (This supplied power to the campus until the construction of the the East Campus Steam Plant in 1926.) The building was renamed the Crowell Building in 1896 in honor of President Crowell's wife (he contributed $8000 towards its construction.)

Crowell later housed a variety of campus uses, including the original "dope shop." It later included a post office. It continues to house a variety of campus life and administrative uses, including the Duke Coffeehouse.

Crowell Hall, looking east, 07.22.10, with the stack from the old campus power plant visible to the left.

Crowell Hall, looking northeast, 08.25.10

Location of the Crowell Building

* * *

Multiple buildings were added to the campus between 1897 and 1905, as the college grew and outstripped the capabilities of its two academic buildings. These included a gymnasium, a library, a chapel/hall, new dormitories for women and men, and new housing for faculty. The college added a preparatory school to the northwest corner of the campus - the Trinity Park School. CC Hook, prominent Charlotte architect (and one partner of Hook and Sawyer - 1902 portfolio available here) who designed many of Durham's prominent buildings, including the Southern Conservatory of Music, the Trust Building, the Academy of Music, and Fire Station #2 would become the de facto campus architect for Trinity College during this period.

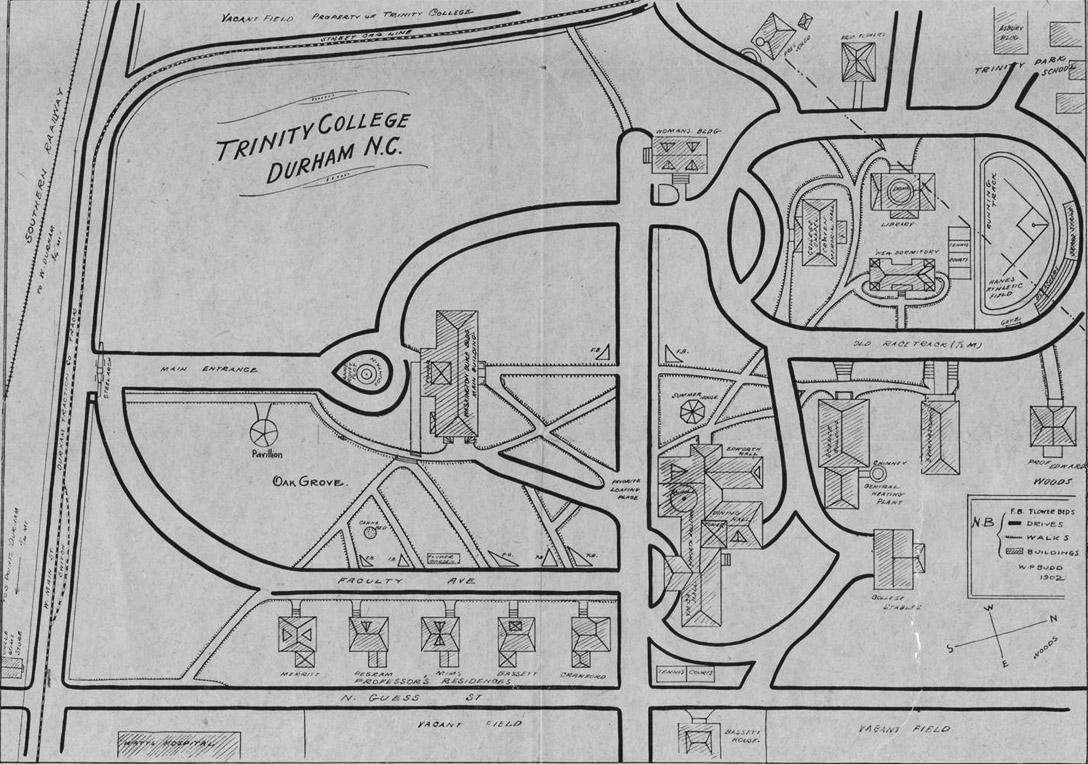

Campus Map, 1902, showing the Washington Duke Building, Faculty Row, the Flowers House, the President's House, Craven Hall, Alspaugh, the library, the Ark, and the Crowell Building.

(Courtesy Duke RBMC - digitized by Digital Durham)

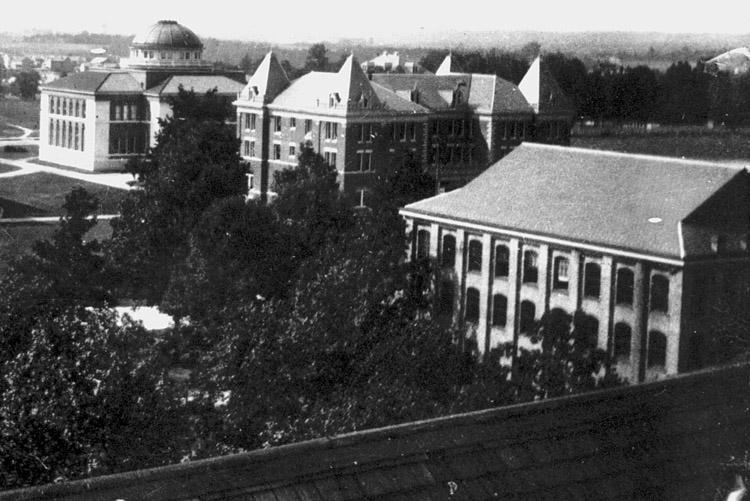

Northwest from the Washington Duke Building, showing the Mary Biddle Duke Women's Building, Craven Memorial Hall, Alspaugh, the library, the President's House, the Flowers house, and Trinity Park School.

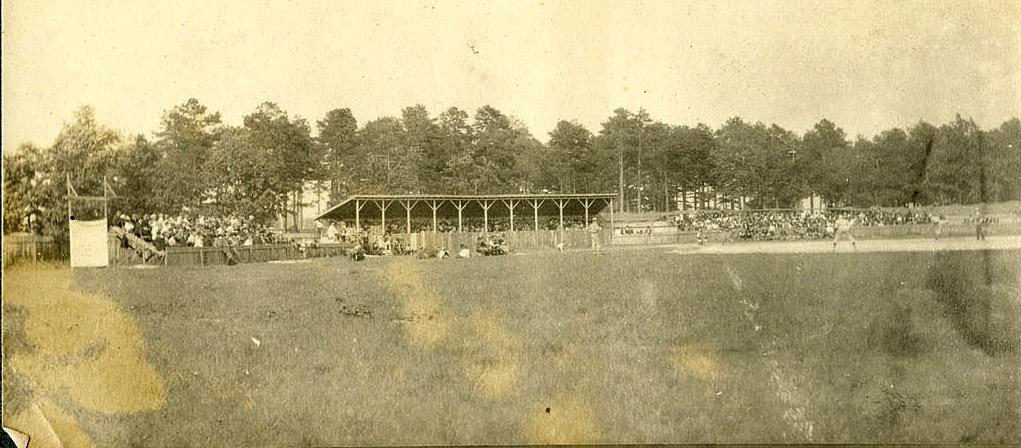

North from the Washington Duke Building, showing the Mary Biddle Duke Women's Building, Craven Memorial Hall, Alspaugh, the library, the Flowers House, and Trinity Park School. The form of the old racetrack is clear, and part of the grandstand remains visible at the northeast turn.

A similar view slightly to the east, showing the Ark and Crowell, as well as the grandstand in the distance.

* * *

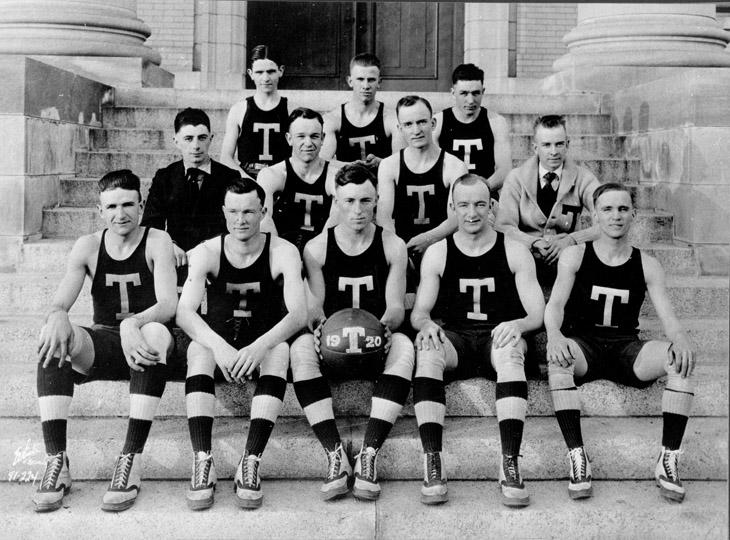

Angier B. Duke Gymnasium / 'The Ark'

Built: 1898

Architect: Unknown

Status: Standing as of August 2010

Built and furnished in 1898 with a donation from Benjamin N. Duke, the building was officially named the Angier B. Duke Gymnasium in honor of his son who was then fourteen years old.

The building is probably the first college gymnasium in the state. The director of the gymnasium from 1899 to 1902, Albert Whitehouse, was the first paid physical education director in North Carolina. Whitehouse proudly boasted of a large and well arranged building equipped with the latest gymnastic equipment, a running track, baseball batting cage, bowling alley, swimming pool, trophy room and shower baths. Formal instruction in physical education took place between Thanksgiving and Easter with outdoor activities scheduled in the fall and spring.

For years campus literature has proclaimed that the Ark was the site of the first intercollegiate basketball game in the state. On March 2, 1906, Trinity played host to Wake Forest in a game which Wake won 24 to 10. When Trinity made plans for the game it may have been the first scheduled. However, the gym had to converted for basketball, a team had to be recruited and trained, and exams had to be completed. By the time the game took place Wake Forest already had played Guilford College. It remains the first so-called "Big Four" basketball game as nearby schools -- Duke, Carolina, State and Wake Forest -- developed intense athletic rivalries."

The court in the Angier gym measured 32 by 50 feet, as compared with a modern collegiate basketball court of 94 by 50 feet.

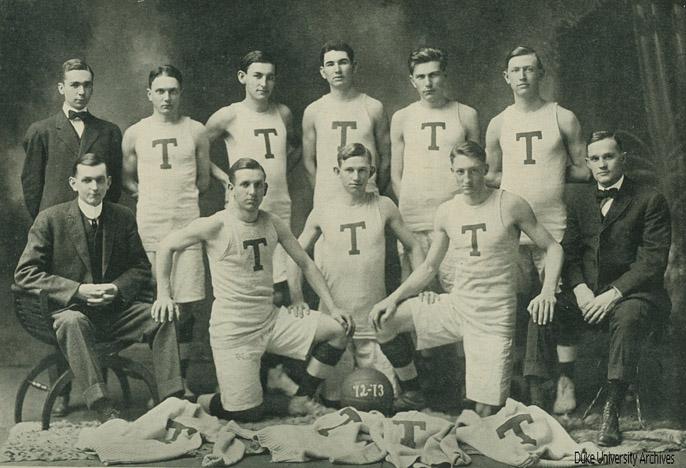

Trinity Basketball team, 1912-1913

"When the more modern Alumni Memorial Gymnasium opened across campus in 1923, the original gym assumed a new identity. Over the next decade as the building was put to a variety of uses, its long narrow bridge-like walkway forced people to enter "two by two;" hence, it became commonly referred to as "The Ark." The long walkway had been a gateway to a race track which was on the site when it was [Blackwell Park]. The Ark, itself, is built from lumber salvaged from the grandstand which was demolished when the fairgrounds was donated for the site for Trinity College.

No longer needed as a gym, the Ark became the cafeteria for men in 1923. The women had their own cafeteria in their new Southgate dormitory. When the new Union opened in 1930, the Ark became the campus laundry.

When West Campus opened and the original campus became exclusively for women, the students felt the need for a social center for relaxation and dancing. Though convenient to downtown, many students had to remain on campus due to financial constraints caused by the Great Depression. The Social Standards Committee of the Woman's Student Government and individual classes set about to renovate the Ark. They purchased curtains for thirty-six windows, wicker furniture, a piano, and Ping-pong and bridge tables. One class spent $175 for a combination radio and victrola and all four of the classes in residence contributed toward refinishing the floor so one could dance in socks without worrying about splinters. The student bands so popular in the West Campus Union Ballroom performed in the Ark every Saturday night and one Wednesday evening per month. Les Brown, Class of 1936, whose Band of Renown is still popular today, began his career in entertainment with one of the student bands that played regularly in the Ark. The Ark became a popular campus meeting place. As The Chronicle reported "Its past was noble; its present is enduring. Who can predict its future?"

Today the building continues in its eclectic tradition. It is primarily used by the Duke Dance Program and the American Dance Festival. On occasion in the summer it has had a snack bar--called the Barre--for dance festival participants. The undergraduate Duke Photo Group has its darkroom in the building. Few buildings on campus have had such a varied and student-centered history.

The Ark, 07.22.10

Angier Duke Gymnasium / 'The Ark'

* * *

Interestingly - for a one-time rural tobacco farmer in the late 19th century - Washington Duke was a strong believer that Trinity should provide women equal educational opportunities to men. In a December 5, 1896 letter to the Eastern Methodist Conference, Washington Duke offered the College $100,000 to become a co-educational institution, stipulating that Trinity "will open its doors to women placing them on an equal footing with men.". Trinity had matriculated and graduated women prior to its move to Durham, as early as 1878 - and women attended the school during its early years in Durham; four women were close to graduation when Duke made his gift. However, they were not allowed to hold residence on campus.

Duke's gift and language attracted national attention - 24 years before women were finally given voting rights nationally; he was even offered a vice-presidential position in a national suffrage organization. (He declined.)

Duke's gift and conditions were accepted by the Board of Trustees in spring of 1897, and the Mary Duke Building was constructed on campus to house the female students, who arrived "in numbers" for the fall semester, 1897.

After the death of Washington Duke, James B and Ben N. Duke continued to seek the expansion of women's access to education at Trinity. By 1904, women still comprised only 10% of the student population of Trinity. That year, the Duke brothers offered land valued at $50,000 "west of Trinity Campus" and $50,000 cash if the Methodists could raise another $50,000 to create a true Women's College on campus. (This piece of land is also described as "the site known as the Tom Lyon place between the NC Railroad and the macadam road just west of Trinity College.") A group of citizens attempted to raise $20,000 of the $50,000 for the Methodists; the effort failed. The Durham Chamber of Commerce took up the cause in the name of economic development from growth of the student body, also stating "It is proposed to have a college that will be the greatest of the kind ever inaugurated in the south in behalf of higher education for the woman. Sometime within the near future it is expected that the announcement will be made that this is a certainty."

Their effort failed as well, and there would not be a true 'Women's Campus' until 1926.

* * *

Mary Duke / Women's Building

Built: 1897

Architect: Unknown

Status: destroyed 1910s.

Mary Duke Building, 1909.

Built in 1896 after Washington Duke's gift of $100,000 to establish equal education for women at Trinity, the Mary Duke Building (named after Duke's daughter) was the first dormitory to house women. However, per the university archives, it soon lost its exclusivity:

"Having a dorm dramatically increased the attractiveness of Trinity for women. However, the first year was controversial but not for the expected reasons. The dorm was finished so quickly it provided more beds than there were female students. President John C. Kilgo quietly picked suitable senior men to share the facility. A professor's wife wrote her daughter, 'Dr. Kilgo has put boys in the Woman's Building so you see it has come down to a mixed boarding house already. If my girl was there I would take her away.' Later records indicate this ironically co-ed dorm may have had nine male boarders, mostly single faculty. The Mary Duke dormitory, sparked by Duke's gift, helped increase the enrollment of women to fifty-four by 1904."

Mary Duke Building, ~1900

I haven't come across any recollection from female students who lived in the building during its ~12 years. One male student wrote that the building was "a very popular place for the male students, [with] one parlor, but a dozen or more cubby holes, staircases, window ledges, and other points of vantage for courting."

One can surmise then, that Trinity as a co-educational institution likely boosted interest from both female and male applicants.

The Mary Duke Building appears to have stood until the 1909 construction of Jarvis Dormitory.

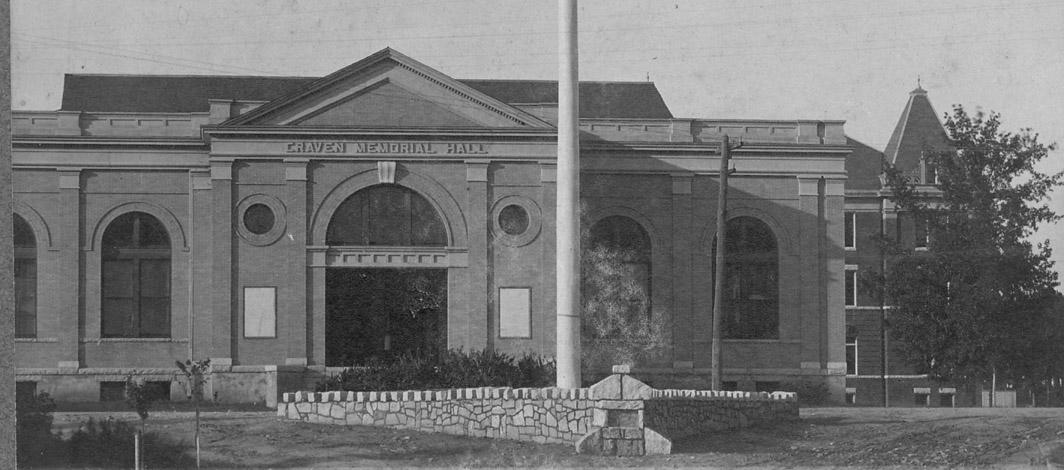

Craven Memorial Hall

Built: 1898-1899

Architect: CC Hook

Moved: 1926

Destroyed: 1972

Craven Memorial Hall was part of the significant expansion of Trinity College that took place around the turn of the century. Prior to its construction, chapel services had been held in the College Inn. Although the rationale behind the construction of Craven isn't specifically known, it isn't hard to imagine that the size of the student body was beginning to outstrip the capacity of the old Inn. Craven was used for performances and commencement as well - thus its more generic name, but it is labelled in a 1910s Trinity Annual as simply "Chapel."

Craven soon after it was built - before the construction of the Library.

After the entry to the college was shifted westward with the construction of the East and West Duke Buildings, Craven became the focal point terminating the entry vista to the college.

It's an interesting perspective to read about how frequently performances were patronized by local citizens, but particularly to read about commencement as a city-wide celebration - with West Main St. festooned in blue and white and Durham citizens coming in force to cheer the graduates.

Craven would stand at this entry point until 1926, when it was removed, evidently along with Alspaugh and the library, to Kitrell College in Kitrell, NC. The three buildings were destroyed by fire in 1972.

Interestingly, John Morrill Bryan, in his architectural tour book of Duke notes that the lamppost just to the west of the East Duke building originally stood in front of Craven, was removed with Craven but eventually retrieved from an antiques dealer and re-installed on campus in 1990.

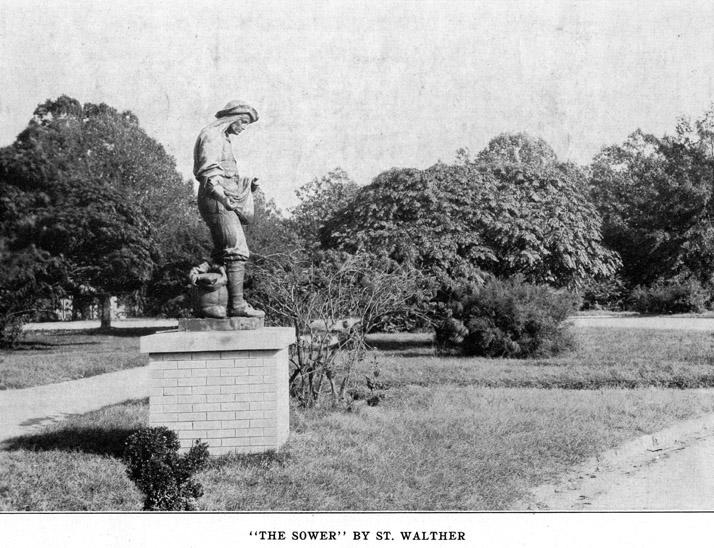

1920 picture of Craven, showing the lamppost and 'The Sower' statue.

Site of Craven in Durham, August 2010

Craven lamppost, 08.25.10

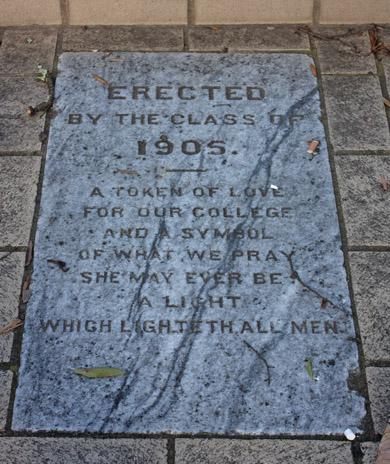

Dedication stone beneath it, 08.16.10

Location of Craven

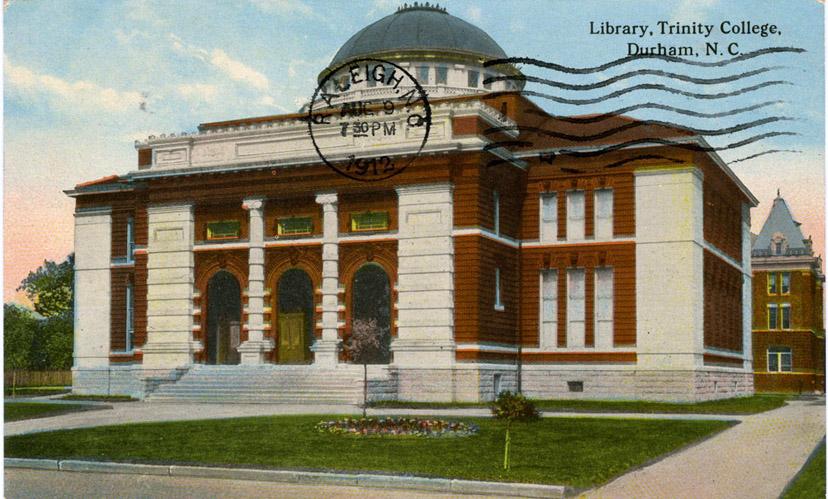

Trinity College Library

Built: 1898-1899

Architect: Hayden, Wheeler, and Schwend

Moved: 1926

Status: Destroyed 1972

For its first 10 years in Durham, the Trinity College library was housed in the Washington Duke Building. One student from each of the two literary societies served as librarians; there was no full-time librarian until 1898, when Joseph Penn Breedlove was appointed the Librarian of Trinity College.

In 1900, James B. Duke donated funds for a library building. Hayden, Wheeler, and Schwend were chosen as the architects - a departure from CC Hook. The building was constructed between 1901 and December 1902, and designed to hold 100,000 volumes. The formal opening took place in February 1903. The college's library holdings numbered 15,000 volumes; Duke donated an additional $10,000 to purchase books for the library.

Breedlove coordinated the move of 15,000 volumes to the newly completed library over the 1902 Christmas break.

In 1927, 100,000 volumes were moved from the library to the new East Campus (now Lilly) library. The original library building was moved to Kittrell College in Kittrell, NC, where it was renamed the BN Duke Library.

Former Trinity College Library / BN Duke Library, at Kittrell College, Kittrell, NC

The library, Craven, and Alspaugh all burned at Kittrell in 1972.

Site of the library in Durham, August 2010

Trinity College Library on Google

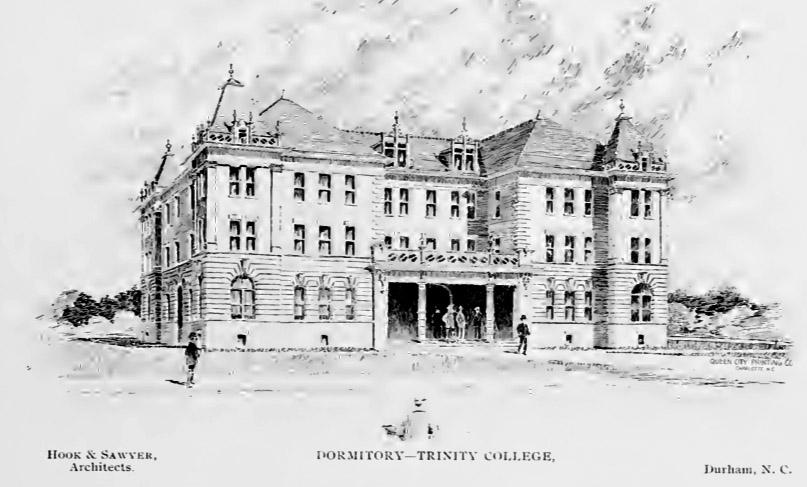

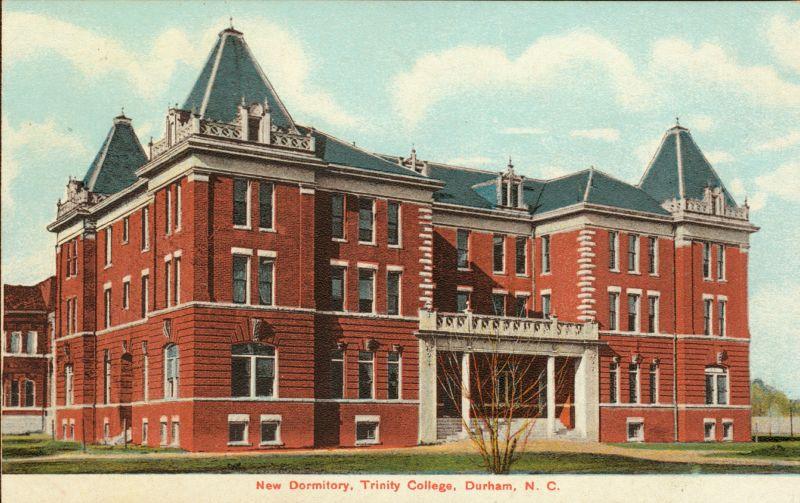

North Dormitory / Alspaugh

Built: 1902

Architect: CC Hook

Moved: 1926

Destroyed: 1972

Rendering, 1902

Alspaugh, looking north, 1907.

North Dormitory was built in 1902 to expand housing for male undergraduates. It was called North Dormitory until 1912, when it was renamed Alspaugh in honor of Colonel Alspaugh, at the time the oldest living alumnus of Trinity College (1855) and evidently a large financial contributor to the college.

Alspaugh remained a dormitory until 1927, when it was deconstructed and moved to Kittrell College, Kittrell, NC. It was destroyed by fire in 1972.

A dormitory on the post-1927 campus, originally named Dormitory #2, was named for Alspaugh in 1930.

Site of North Dormitory / 'Original Alspaugh' in Durham, August, 2010.

Location of 'Original Alspaugh' on Google

Flowers House

Built: 1900-1910

Architect: CC Hook

Destroyed: 2006?

Robert Flowers was one of a handful of faculty who moved with Trinity College from Trinity to Durham, teaching electrical engineering and mathematics. Demonstrating the all-hands-on-deck mentality of a Naval Academy graduate, Flowers wired the new Durham campus for electricity himself. In the first decade of the 20th century, he built a house on campus, designed by CC Hook. He moved out of the house by 1930, And in 1932, it became the home of Alice Baldwin, the first Dean of the Women's College, and later, the subsequent two deans of the Women's College - until 1965. Flowers served as President of Duke from 1941-48, and subsequently became chancellor.

By the 1970s, the house was used by the "Institute for Learning in Retirement."

Unfortunately, it was torn down in 1994 for the construction of Blackwell dormitory.

August 2010.

Site of the Flowers House on Google

President's House

Built: 1901

Architect: CC Hook?

Status: Destroyed 1957

Little information is available regarding the President's House, or what function it served after the construction of the President's house at the entry to Duke's West Campus in the 1920s. It was likely designed by CC Hook and built contemporaneously with the Flowers House.

The house appears to have been torn down in 1957 for the construction of Gilbert-Addoms dormitory.

August, 2010

Location of the President's House

Edwards / Robertson House

Built: prior to 1902

Status: Demolished ~1960s

There is little to no information available about the Edwards/Robertson house. It is labelled as "Prof Edwards" house on the 1902 map above, and as "Robertson House" on the 1937 and 1950 Sanborn maps.

Edwards/Robertson House, looking east, 1925. Brown dormitory is under construction in the foreground.

Anne Roney Fountain

Built: 1901

Status: Damaged/non-functional, but basin is still present as of August 2010

Looking south, ~1900.

The Anne Roney Fountain originally was situated in a prominent position directly in front of the Old Main / Washington Duke Building. Roney was the sister of Artelia Roney, Washington Duke's second wife. Anne helped Duke raise his children after Artelia died, and was housekeeper at Fairview, his house on the southeast corner of South Duke St. and West Main St..

After the demolition of the Washington Duke Building in 1911, the construction of the East Duke Building, and the movement of the entrance to Trinity westward, the fountain became a bit of a relic.

August, 2010

In January 2011, after the original publication of this piece, Duke dug up the fountain and moved the entire structure to Duke Gardens.

While it's nice that the fountain will be operational again, it's regrettable that this tie to the original Trinity College campus entry and the Washington Duke building has been erased.

Location of the Anne Roney Fountain

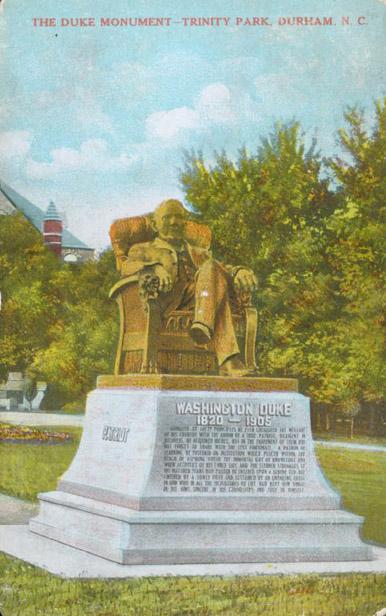

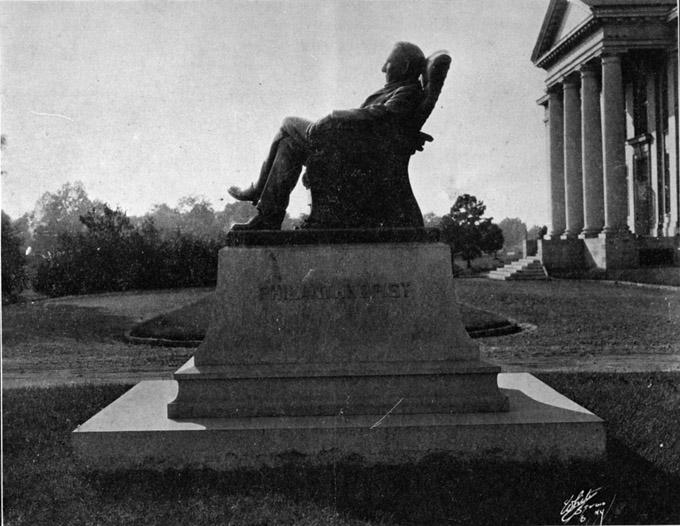

Washington Duke Statue

~1908

Commissioned after the death of Washington Duke in 1905, and created by Edward V. Valentine, who has design a well-known seated statue of Robert E. Lee, and a statue of Thomas Jefferson at UVA, the Washington Duke statue is well-travelled. As can be seen in the undated photo above, it was originally placed in front of the Washington Duke Building on , 1908. It remained in the same place immediately after the construction of the East and West Duke Buildings.

However, shortly after the shift in the entryway to Trinity College in ~1912, the statue was place atop a small hill just to the south of the East and West Duke buildings, centered in the roadway.

With West Duke in the background, 1915

In 1921, it was moved again, to a position between the two buildings, with the monument placed on grade.

8.16.10

Bishop (Kilgo)'s House / Faculty Club / Infirmary

Built: 1910

Architect: Unknown

Status: Standing as of August 2010.

Built as a residence for Methodist Bishop and former Trinity College President John Kilgo, the Bishop's House later became a Faculty Club, and during the mid-20th century served as the infirmary. It currently serves as the center for Continuing Education at Duke.

Bishop's House, 07.22.10

Location of Bishop Kilgo's House

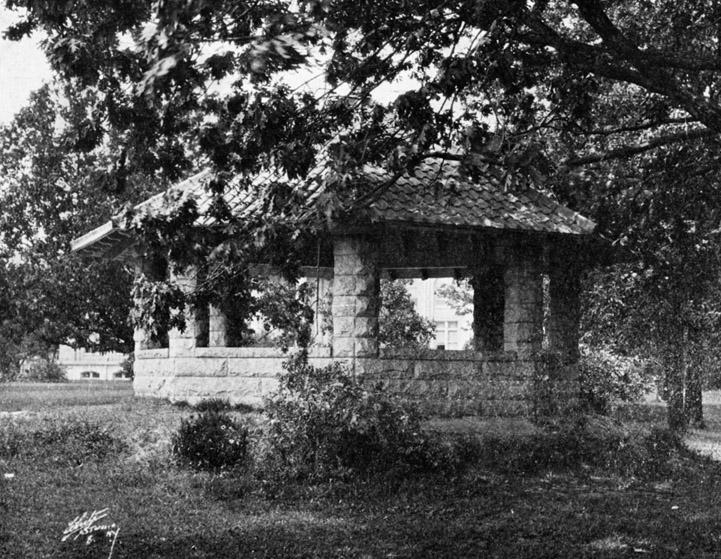

Stagg Pavillion

Built: 1902

Status: Standing as of August 2010

Built in 1902 with a donation of funds from Mrs. Mary Lyon Stagg, a daughter of Mary Elizabeth Duke Lyon, who was a sister of James and Benjamin Duke, the Stagg Pavilion bears a resemblance to the Rotary Park pavilion, built in 1916, and now located at Bennett Place

August, 2010

Location of the Stagg Pavilion

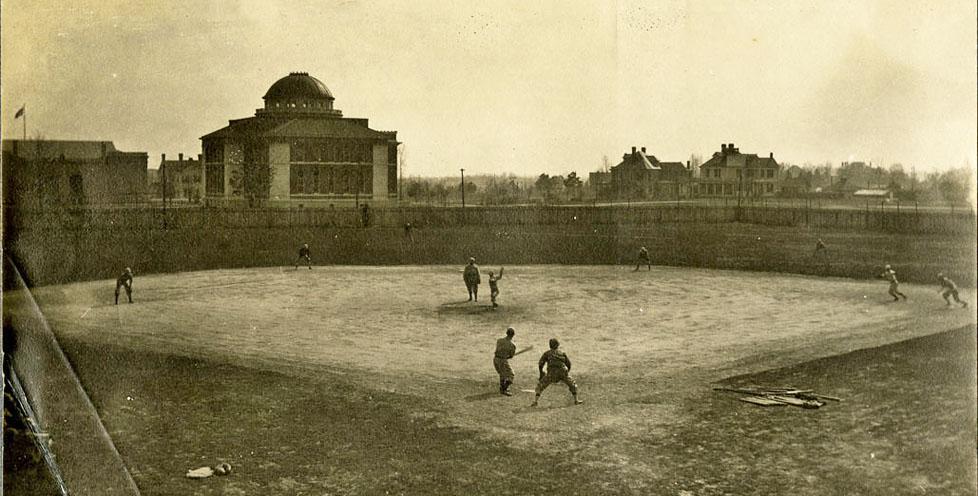

Hanes Field

Built: 1899, remodeled 1914.

Status: Currently Williams Field / Jack Katz Stadium, used for Field Hockey.

The original athletic field at Trinity College was established at the north end of the former racetrack oval:

Trinity Athletic Field, looking southwest with the library in the background, 1909.

Grandstands, looking north, 1909. These may have been the original grandstands from the racetrack.

Baseball games seemed to be well accepted as the principal intercollegiate sport of the day, and the field was a well-regarded facility - so much so that it was used for spring training by Boston in 1899, and by the Durham Bulls upon the re-establishment of their club in 1913.

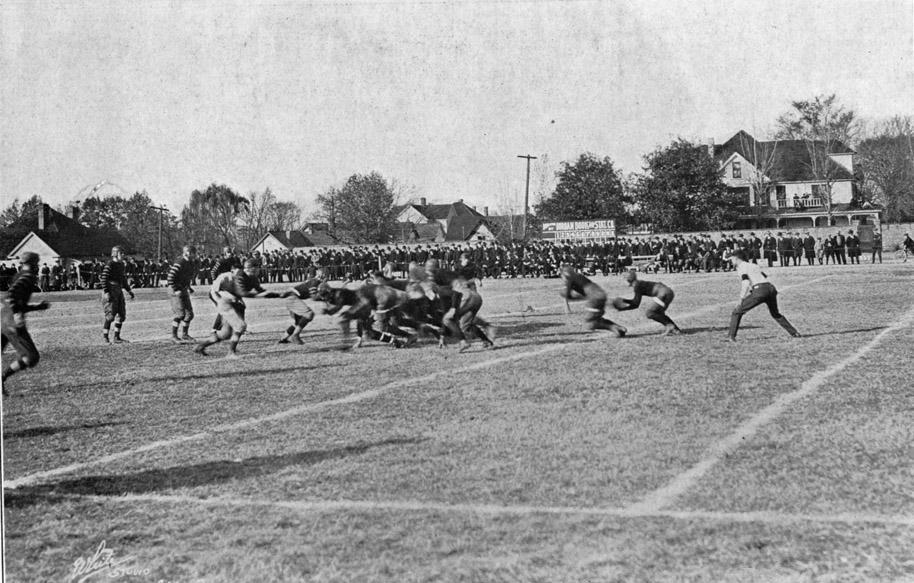

University President Crowell was instrumental in establishing intercollegiate football at Trinity, believing strongly that the sport was an essential part of the development of the students. The Trinity College Roosters (yes, Roosters,) wore blue and white and played against familiar faces - State College (NCSU), UNC, Wake Forest.

Wyatt Dixon recount stories told by HE Spence about early football and its abolition for ~21 years at Trinity.

Football was an important part of the athletic program of Trinity College during the early life of the institution in Durham, as it is today with Duke University. For several years, the sport pitted Trinity against their rivals from the University of North Carolina and Wake Forest College, and with other teams also. Dr. Hershey E. Spence. in his book "I Remember” credits Dr. John Franklin Crowell, president of Trinity College when it was moved here from Randolph County with bringing football to the college. The sport was abolished later after Dr. John C. Kilgo, then president of Trinity and Dr. Robert L. Flowers, for many years prominently identified with Trinity and Duke, was "grossly insulted" at a game.

Dr. Crowell played an active role in the football program of Trinity, coaching some of the earliest. Interest in the sport grew steadily, and in a few years "had grown to where enthusiasm was at a white heat," Dr. Spence said. Some of the scores were so small they sounded like baseball scores. One game ended with the score of 6 to 4. The extreme in high scores also was noted. According to the football report in the book, Trinity defeated the University of Tennessee by the score of 70 to 0 and took a game from Furman by the score of 96 to 0.

The Trinity team scored so often and so fast that at one stage of the game the referee noticed that Furman had only ten men on the field. The captain was discovered leaning against his own goal post. When ordered to come on down and get into the game he replied: 'No thanks, they’ll be here again in a couple of minutes. I’ll just wait for them here.

The type of refereeing was a source of complaint and criticism and complaints were made of the unfair play by opposing players. Dr. Spence tells in his book of a game between Trinity and the University of Virginia. Trinity forfeited the game because the referee was ‘cheating’ them. Trinity claimed that the Virginia team was either offside or held the Trinity players, which violations the referee admitted seeing but declined to do anything about. As a result the Trinity team walked off the field.

Opposition to the game gradually developed throughout the state. Complaints were made that the game was too rough. . . . President Crowell wrote a lengthy article defending the game and hailing it as one of the greatest of morale builders. But the opposition mounted. The Western North Carolina Conference of the Methodist Church passed resolutions declaring it would not support Trinity financially if it continued the barbarous sport. It is not quite clear what was the final 'straw that broke the camel's back.' Rumor had It that the final decision to abolish the sport came after a game in which President Kilgo and Dr. Flowers were grossly insulted at a neighboring institution. It is not certain as to whether or not the offenders were students, but a group of persons are said to have shaken their money close under the noses of these two gentlemen and in obscene and profane language dared them to bet on their team.

Football was discontinued intercollegiately but was allowed as a campus sport between classes until the end year of my college life. Then one day a student broke an arm or and President Kilgo forbade any further participation whatever in the sport.

Hanes Field, named after John Wesley Hanes, who started the Hanes Hosiery Company in Winston-Salem in 1901, was the primary athletic field for both baseball and football at Trinity College. - it appears to have been built in the mid-1910s.

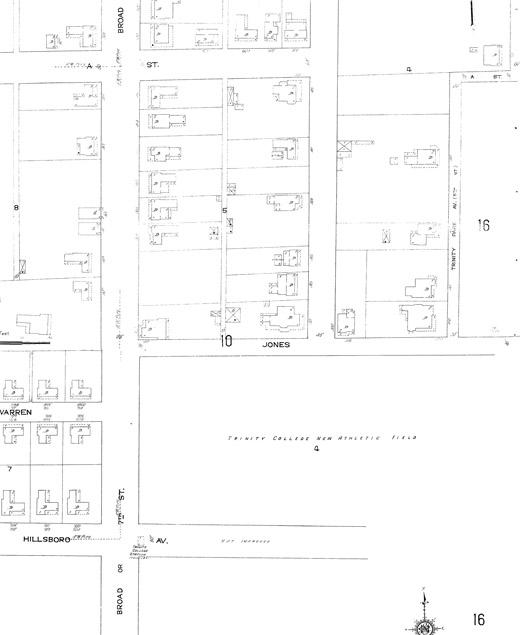

In understanding the background in these two photos, it's helpful to know that the northwest corner of what is now East Campus was part of Old West Durham until the 1920s - note the position of "A St." (i.e. West Markham) and Broad in the map below - with Jones St. and Trinity Park Ave. forming an inside corner that has since been claimed by Duke.

Trinity Football, with Alumni Memorial Gymnasium in the background, mid-1920s.

The use of the field for intercollegiate athletics is unclear during the period of 1927-1996. In 1996, the field was renovated as a Field Hockey field, and renamed Williams Field / Jack Katz Stadium

August, 2010

Location of Hanes Field

* * *

Trinity College matured as an institution during the first decade of the 20th century, becoming a fast-rising star in the academic world. It achieved national prominence / notoriety in 1903 during the Bassett Affair, which would come to be seen as a progressive and brave stance for academic freedom, one which made the academic world take notice, and put Trinity on the national stage.

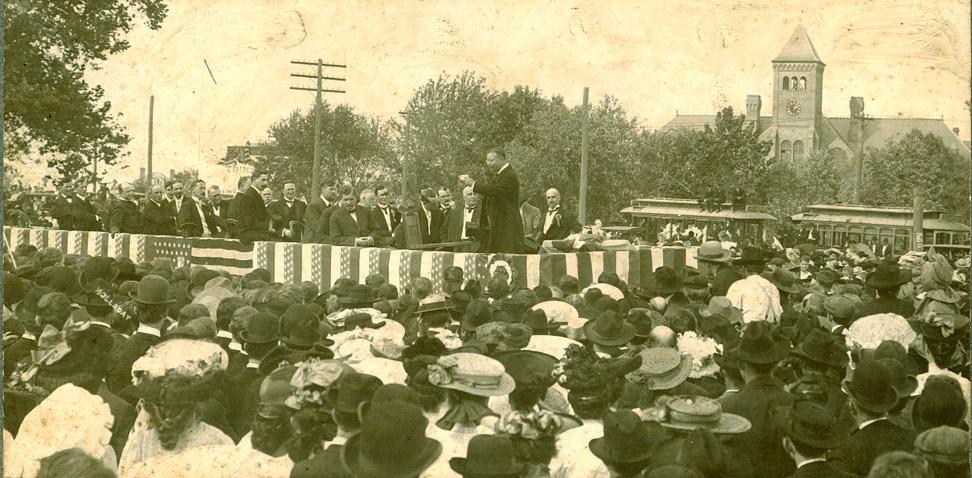

T. Roosevelt speaking on his railroad car with the Washington Duke building behind him, 1905.

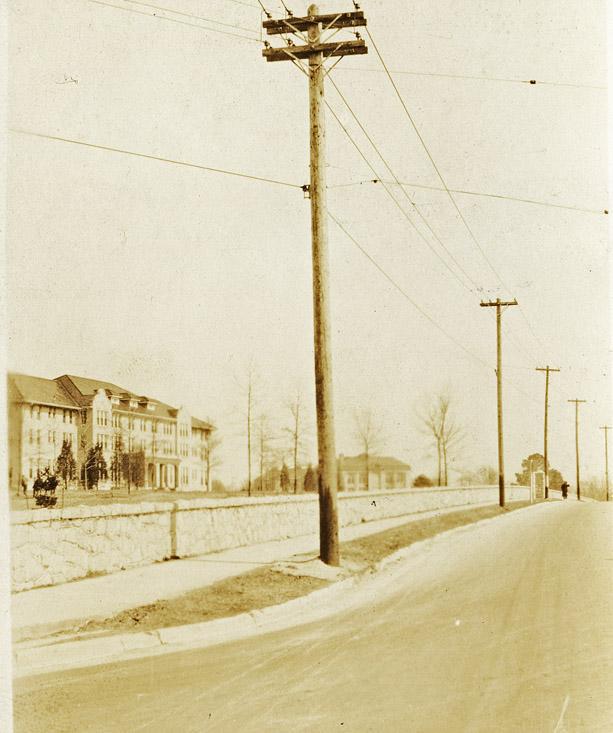

A second period of major construction and expansion occurred on the campus ~1910-1912, directed by architect CC Hook. This would involve moving the entrance of Trinity College westward to intersect with Craven Memorial / the long axis of the racetrack oval. (The previous entrance and its relation to the racetrack oval is best appreciated in the 1902 map of campus above.

Trinity Entrance, ~1911. West Duke is complete and East Duke is near completion. The Mary Duke building is still visible in the background and the wall has not been constructed around the campus.

New entrance to Trinity College, ~1916. Jarvis is visible in the background, and the wall around the campus is completed.

Thematically, the architecture would be a combination of the neoclassical East and West Duke Buildings - framing the entry to the campus and providing new administration/academic space, and the more eclectic (I'd say quasi-Renaissance Revival) Jarvis and Aycock dormitories immediately to the north of the East and West Duke buildings. Green tile roofs, white pressed brick and Indiana limestone were used throughout. These four buildings formed 3 sides of a square, open to the north with Craven in the center of the fourth 'side' as the southern point of the Alspaugh, Library, Craven triangle of buildings. Hook intended the quadrangle formed by these buildings to be used for social space, and termed this the 'Yard' - likely in emulating Harvard Yard

* * *

East and West Duke Buildings

Built: 1911-1912

Architect: CC Hook

Status: Standing as of August 2010

The East and West Duke Buildings were under design before the Washington Duke Building burned in 1911; the plan was already being developed to demolish Old Main and replace it with two new academic and administrative buildings. The East and West Duke Buildings would also shift the main entry of the campus to align with the central axis of the original racetrack, and the three buildings within that oval: Craven, the LIbrary, and Alspaugh.

As is clear from the drawing above, the original plan was to build a connecting colonnade walkway between the buildings with a central tower - it appears that vehicles would pass through arched openings beneath the tower. Why the tower and connecting walkway weren't built isn't clear - practicality and money probably had some influence on the decision.

East Duke served as the administration building for Trinity College and, later, for the Women's College. The West Duke Building contained the college barbershop, bookstore, post office, and held a theater in the basement. The psychology (and parapsychology) departments were located on the 2nd floor after 1935.

East Duke, August, 2010

West Duke, August 2010

Location of West Duke

Location of East Duke

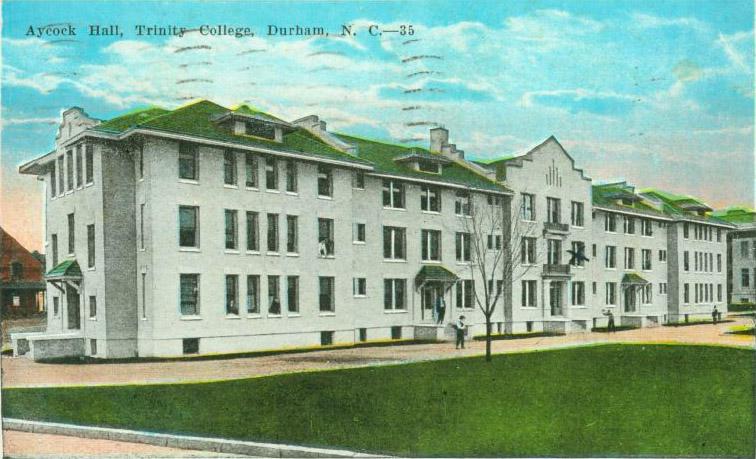

Aycock

Built: 1911

Architect: CC Hook

Destroyed: Standing as of August 2010

Named for North Carolina governor Charles Aycock (1900-1904) Aycock was built as a one of a pair of dormitories (with Jarvis) that framed what architect CC Hook called "The Yard."

August, 2010

Location of Aycock

Jarvis

Built: 1912

Architect: CC Hook

Destroyed: Standing as of August 2010

Named for North Carolina governor Thomas Jarvis (1879-1885), Jarvis was built as a companion dormitory to Aycock, across what architect CC Hook called "The Yard."

A small portion of Jarvis on the left, looking north towards Craven Memorial

August, 2010

Location of Jarvis

The Sower

Built: 1914

Status: Standing as of August 2010

Sculpted by Stephan Anton Friedrich Walter, The Sower is one of several statues James B. Duke bought for his New Jersey estate. The Sower was located at Duke Farm until 1914, when Trinity president John Kilgo mentioned to Duke that he admired the statue; Duke sent the statue to Durham, and Trinity placed the Sower in front of Craven Memorial Hall. When Craven was demolished, the Sower was placed on the former entry path to the campus, near the Stagg Pavilion.

***

In 1916, the Faculty Row houses were removed to points off campus, and a stone wall was constructed around the perimeter of the campus (with the exception of Hanes Field, which retained its brick wall.) The campus had grown significantly, and contained three distinct architectural 'areas' - the remaining original 1890s buidings, along the eastern side of the original racetrack, the three circa-1900 buildings within the oval of the racetrack, and the four circa-1910 buildings framing the Yard.

Northeast view of the Trinity College Campus: East and West Duke, Jarvis, and Aycock form a squared entry to the campus, with the triangle of Craven, Alspaugh, and Library immediately to the north, within the old racetrack. The older Angier Gym, Crowell Building, and Epworth are to the east. The President's house and Flowers' house are in the foreground, to the west, and the Kilgo/Bishop's house in the background to the northeast. Goalposts are visible in the northern part of the oval, attesting to its use for sports.

Similar view of the campus, looking eastward.

At the subsequent decade mark, only two new buildings would be added to the campus, but a major overhaul was impending.

***

Southgate Dormitory

Built: 1920

Architect: CC Hook

Status: Standing as of August 2010

Many pieces of historical record attest to the different relationship once enjoyed between Trinity/Duke and the citizenry of Durham - particularly on the part of Durham-folk, one of pride in 'their' institution.

In that context, it is less surprising that the people of Durham raised funds through a subscription drive to build Southgate dormitory, and name it in honor of James H. Southgate, Chairman of the Trinity Board of Trustees. Then Trinity President William Preston Few issued this statement regarding the fundraising drive to construct the building

"The executive committee of the trustees have directed me to thanks the citizens of Durham for making the James H. Southgate memorial in the form of a building for women at Trinity college and also to thank the people of the whole community for their hearty cooperation in the undertaking which this Friday [March 26, 1920] at noon became a glorious success.

The movement began with $100,000 offered by a friend of Durham and a friend of Trinity College, on condition that at least $100,000 in addition be raised. Durham's answer is to date $110,000 and other contributions will come from friends of Mr. Southgate and of the cause here and elsewhere.

The college gratefully accepts the trust and will undertake to administer it in such a way as to do the most good. The building will be begun at the earliest possible moment.

The value of the college to the town from the business viewpoint has received some emphasis, and that is well. But everybody will of course always expect the college to be influenced not by commercial value and to go forward along solid lines and with high aims rather than take short cuts that lead to mushroom growth and doubtful success. Especially will all our people need patience as administrators of higher education seek to adjust the processes of intellectual training to the new responsibilities that are coming to the women of America.

Mr Southgate saw before most men that women were to have a larger and juster share in the life of the world. Trinity was among the first of the colleges, if the not the very first, of the colleges for men in the old south to offer to women opportunities of higher education. This memorial, in this form, in this place, seems then most appropriate and we are all most grateful for it.

I am particularly grateful that Durham united whole-heartedly in this campaign. It means much for the college and for the town. With this unity made permanent Durham can become the most influential center of population in North Carolina. I am glad that Durham in this great way has honored one of her noblest sons. Durham is blessed perhaps above every other town in the state with public-spirited citizens and generous benefactors. It is well for us to give expression to our gratitude and now we have set an example that is sure to be followed not only here but elsewhere.

...

Southgate would open as a dormitory for female students that year and would remain so for a period after Trinity became the Women's college. For a brief period during the 1930s, though, the building housed male engineering students - in the late 1930s it reverted to a women's dormitory, which it remained until after 1972.

Southgate, looking east from Broad St., 1920s.

Southgate, looking northwest, 08.22.10

Location of Southgate

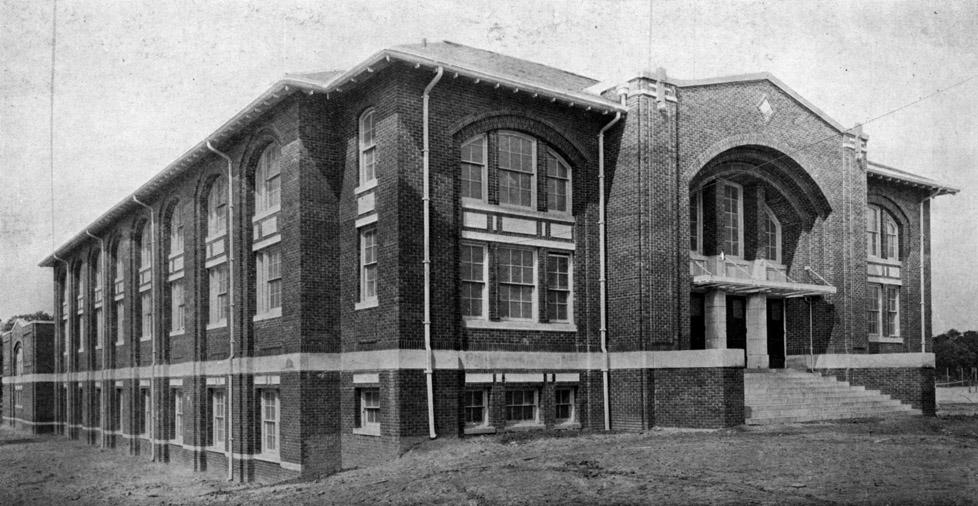

Alumni Memorial Gymnasium / Brodie Recreation Center

Built: 1922-3

Architect: CC Hook

Status: Facades heavily altered 2006

Built in 1922-3, opened in 1924, and named as a memorial to Trinity College students who died in World War I, Memorial Gym cost $150,000 to build. The gym served as a replacement for the Angier B. Duke gymnasium, and $25,000 was provided by Angier (who graduated from Trinity in 1905) and his sister Mary.

Trinity Basketball team, mid-1920s.

The gym was the first home of Duke basketball (as opposed to Trinity basketball) as it served as the primary gym for the College/University until it was supplanted by Card Gym on West Campus in 1930. It then served the Women's college as the East Campus gym, relatively unchanged, over the next 50 years. in 1975 racquetball courts were added to the gym. In 1996, a 31,000 sf addition was built, and the overall facility was renamed the Brodie Recreation Center, after Duke president HKH Brodie (1985-1993.)

08.16.10

Looking northeast, 08.25.10

Location of Memorial Gym

* * *

The story surrounding the massive gift that would transform Trinity into Duke University is often told in such brief form that it seems a philanthropic-minded James B. Duke simply chose a college out of a random assortment in order to rename it with the Duke name. As is clear from the history above, the Duke family had given significant amounts of money to build and sustain Trinity College after its move from Trinity, NC to Durham - over a period of 30+ years prior to JB Duke's gift. I think this brevity also gives rise to the apocryphal stories of Duke being initially turned down by Princeton or fill-in-the-blank college.

So the gift, while massive and transformative, was the culmination of a familial effort that had, to that point, been more the province of Washington and, subsequently, Ben Duke than James "Buck" Duke. JB Duke had left Durham for New York City in the 1884 - he who later owned houses in Charlotte, Newport, and New York City never appears to have owned a house in Durham. Focused with great intensity on building the American Tobacco Company, textile mills, and the Southern Power Company (later Duke Power,) James B. Duke paid only moderate attention to the affairs of Trinity College or of Durham-as-city - and generally only using his brother Ben as a conduit - until the late 1910s.

After Ben became progressively more ill in 1917, he moved to Florida to attempt recuperation. His strong relationship with Trinity president William Preston Few had been one that Few had relied on to provide financial sustenance for the college. With Ben out of Durham and more difficult to interact with, Few began to try to build a more direct relationship with James B. Duke. JB Duke seems to have responded to the illness of his brother, with whom he was as close as JB Duke was to anyone, with a sense of some new responsibility to attend to charitable causes.

This was no easy task, and Few still relied on Ben and tobacco executive Clinton Toms frequently to act as go-betweens. Few seized upon the idea pushed by George Watts to establish North Carolina's first four-year medical school at Trinity, with Watts Hospital as its base. The idea foundered, particularly after the death of Watts in 1921, and the legislature's move to establish a 4 year medical school at UNC in 1922.

The correspondence between Few and Duke concerning the medical school seems to have more significantly captures Duke's attention, as he moved towards the establishment of a larger charitable foundation with support for Trinity at its core. It was Few who suggested that the college be renamed Duke University - in great part, I'm sure, by an ongoing attempt to woo JB Duke, but also, ostensibly, because there were already quite a few Trinity schools around the country and world, and a name change would distinguish a new institution.

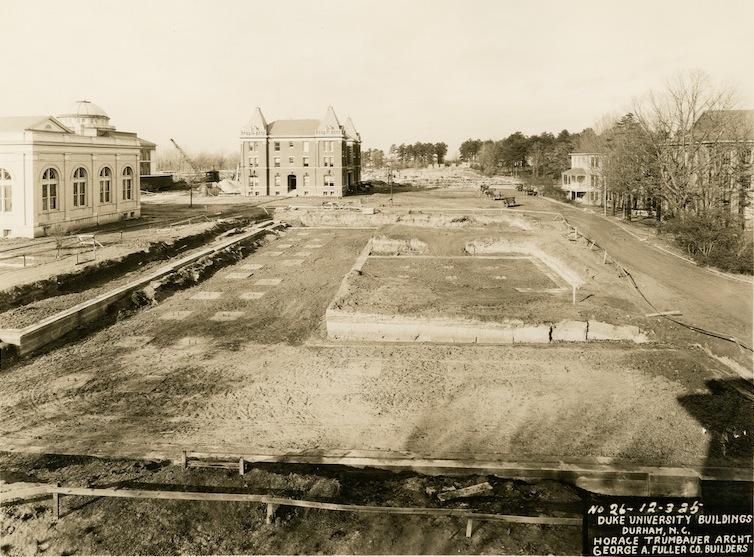

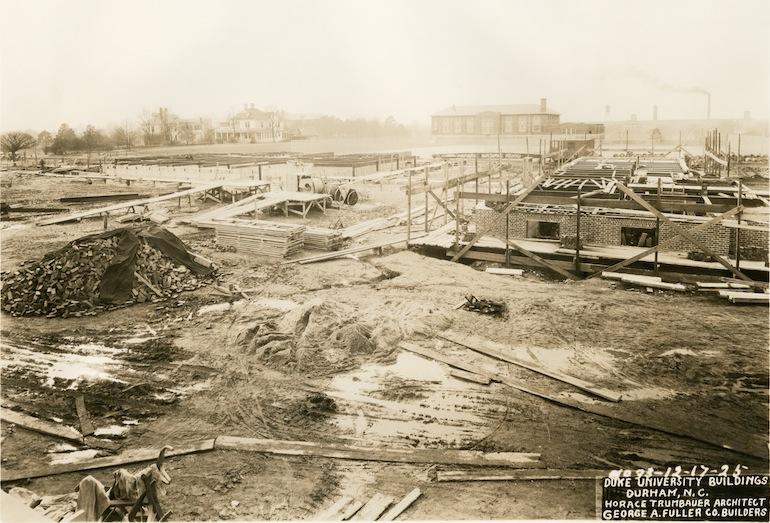

By 1923, Duke had tasked the architect who built his house on Fifth Avenue in New York as well as some greenhouses on Duke's Farm, Horace Trumbauer of Philadelphia, with corresponding with Few to begin planning expansion of the college. Duke showed a particular affinity for the Tudor Gothic style he had seen at Princeton, and Few drew inspiration from the buildings at Bryn Mawr. They took inspiration as well from the Widener Library at Harvard that Trumbauer and his lead architect, Julian Abele had designed, as well as Johns Hopkins and the University of Virginia.

Duke gathered his family, lawyers and associates at his house in Charlotte in December 1924 and announced that he had been working on the form and establishment of a philanthropic foundation for a number of years, and that he wanted to complete it then, by working around the clock. On December 11, 1924, the Duke Endowment was established by transfer of $40,000,000 of Securities from JB Duke to the endowment. 46% was for education, 32% for hospitals (both white and African-American,) 12% to the Methodist church, and 10% to orphanages (both white and African-American.) The educational portion was subdivided with 32% was to go to support Trinity/Duke, 5% to Davidson, 5% to Furman, and 4% to Johnson C. Smith University.

On December 29, 1924, the Trustees of Trinity College accepted Duke's offer, and changed the name of the school to Duke University.

Robert Flowers initially sought land to the north of the College campus; some of the thinking may have remained that establishing a link with Watts Hospital was desirable, and that the University would grow north to West Club Blvd. Some land was acquired (now the location of Duke's Trinity Heights development,) but the price of the remaining land necessary skyrocketed with news of the endowment. Land south of the college, across the railroad tracks was examined as well, but the price was too high there as well.

Durham's landowners seeing too much green when the big entity comes calling nearly cost Durham dearly. Frustrated by his inability to acquire land near Trinity College, JB Duke was receptive to an offer of 1000 acres in Charlotte, the center of his Duke Power empire, and threatened to move the establishment of a university to Charlotte if more land was not acquired soon. Fortunately for Durham (although at a cost we continue to pay in the physical separation of the core of Duke and downtown Durham) the old Rigsbee Farm on Rigsbee Road - totaling 2400 acres - was remembered by Few from horseback riding as a young man. Flowers was able to acquire a much larger quantity of land than originally intended, cheaply - although far outside of the core of town.

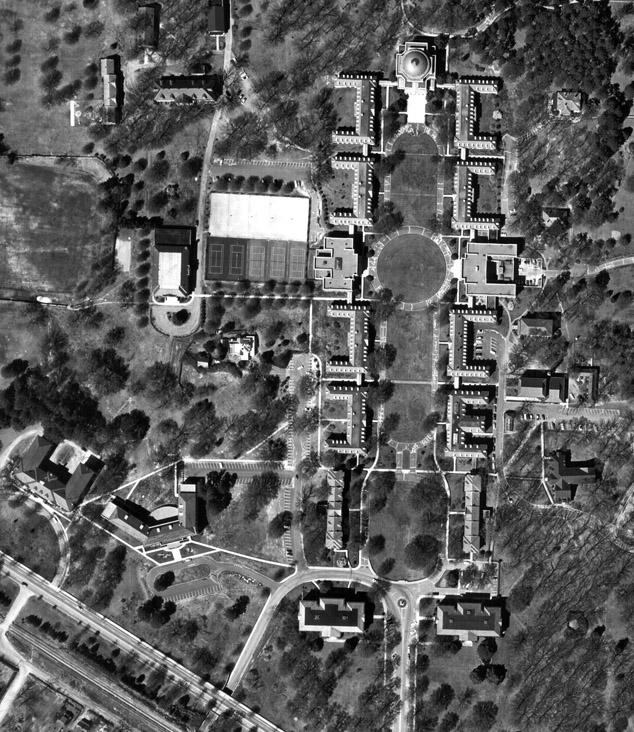

Trumbauer and Abele scouted the sites and devised conceptual plans. While the new men's campus was being designed in a Gothic style from Hillsborough stone, Abele chose a colonial revival style, reminiscent of the University of Virginia, for a major redesign of the Trinity College Campus, which would be re-purposed as the Women's College of Duke University - with men and women at the rechristened university segregated by the length of Campus Drive. The Olmstead Brothers of Boston were hired as landscape architects for both campuses.

Rather soon after commencement of these plans, James B. Duke died at age 68 in New York. With his will, and the previous endowment, he gave $19 million to Duke for construction of a new campus.

Construction began in earnest in 1925. On the former Trinity Campus, the early Crowell Building, remaining College (Epworth) Inn, and the Ark, along with a few faculty houses would be retained - as would the buildings constructed during the ~1910 campus renovation: East Duke, West Duke, Jarvis, and Aycock, and the 1920s buildings: Southgate and Alumni Memorial Gymnasium.

However, the former Alspaugh, the old Library, and Craven Memorial Hall would be removed to create a continuation of the open 'quad' between Jarvis and Aycock, terminating in the Chapel (later known as Baldwin Auditorium.)

Fascinatingly, Alspaugh, Craven, and the Library were moved from the campus to historically African-American Kittrell College, in Kittrell, NC. The Duke family had supported Kittrell, which opened in 1886 and was associated with the AME church, for many years, and Ben Duke, after the movement of the buildings to Kittrell, would give the college a gift of $203,000. (Unfortunately, the buildings burned to the ground in 1972 and Kittrell College ceased to operate in 1975.)

See the former location of Kittrell College on a Google Map

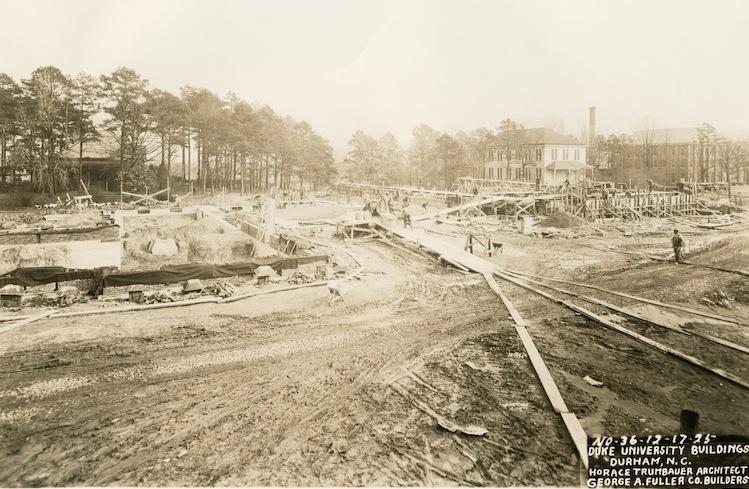

Sitework and initial construction began with Craven, the Library, and Alspaugh still in place. Below, the Science building is laid out just to the east of Craven Memorial Hall, looking north from near Aycock, 12.03.25

Below, the Carr Building is laid out, just to the west of Craven and to the north of Jarvis, 12.03.25

Alspaugh - with the tennis courts and Trinity Park School in the background, 12.3.25

Beginning construction of the Union, looking northeast, 12.16.25

East Campus Library, with the Alumni Memorial Gym, Flowers House, and President's House in the background, 12.17.25

The Union and Faculty Apartments, looking east, with the Robertson House, the Ark, and Crowell in the background, 12.17.25

Construction of the auditorium, looking south, 02.01.26. The original Alspaugh, Trinity College Library, and Craven are still visible in the background.

02.15.26

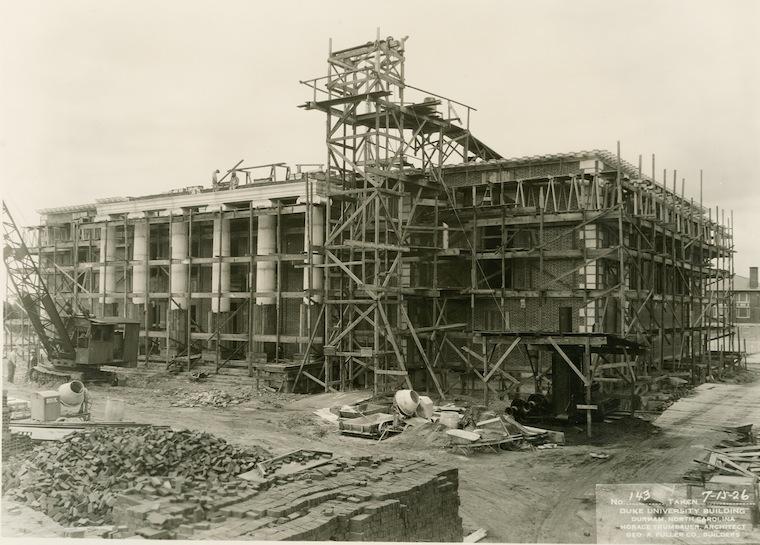

Science Building, looking south towards Aycock04.01.26

Carr Building, looking south towards Jarvis, 04.15.26

Science Building, with Epworth in the background, 03.16.26

Union, 06.01.26

Brown and Bassett, 06.15.26. The railroad line brought onto Campus for construction is apparent.

Alspaugh and Pegram, 06.15.26

Library, Bassett, Pegram, 07.15.26

Union, 07.15.26

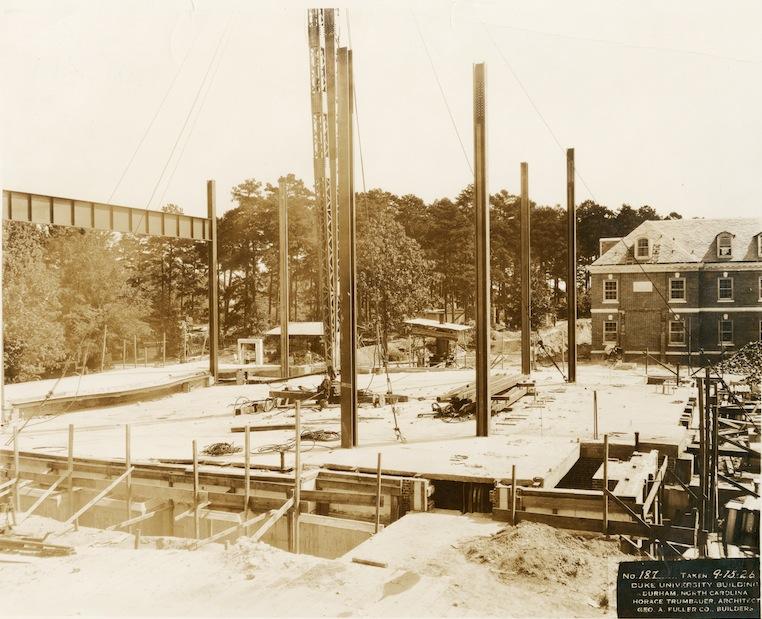

08.01.26

08.01.26

08.16.26

09.01.26

09.01.26

08.01.26

08.01.26

08.16.26

09.01.26

09.01.26

09.15.26

09.15.26

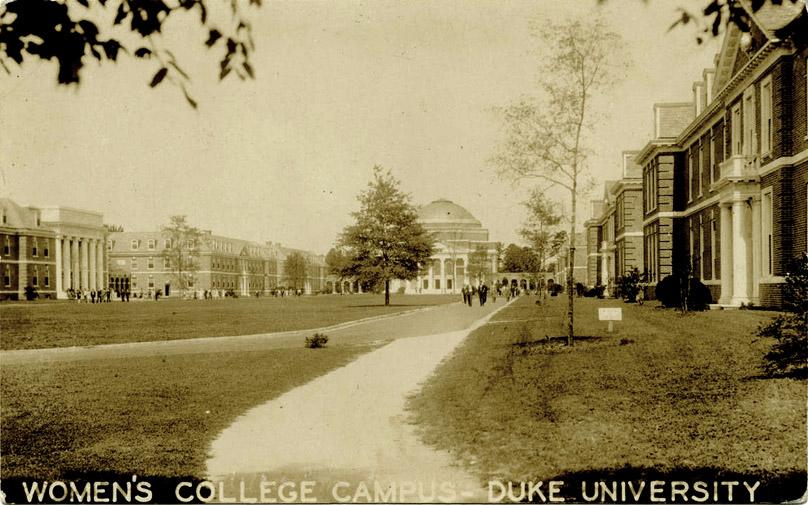

Once completed, the former Trinity College campus officially began its transition to the Women's College of Duke University. The dominant architectural feel of the campus became Georgian, with Hook's former focal point around the 'Yard' serving primarily as a traffic circulation point, and the focus shifted northward towards the Auditorium, later renamed for the woman who would become the first Dean of the Women's College, Alice Baldwin.

The transition was completed in 1930, with the installation of 'Trinity College' (the men's college) on West Campus and the Women's College on East. The Engineering School was also located on East Campus, in the former Trinity Park High School

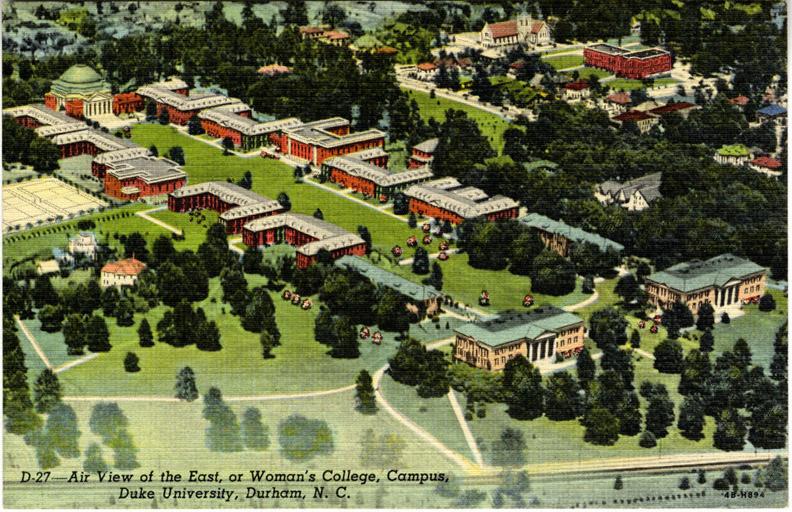

Campus Aerial, 1940s.

Looking northwest, 1950s

1950s

1950s

Aerial of the campus, with north to the left, 1959.

Carr

Built: 1926

Architect: Trumbauer / Abele

Status: Standing as of August 2010

Named after Julian Carr, the Carr building was constructed as, and remains, an academic building.

August, 2010

Location of Carr

Science Building/Art Museum/Friedl Building

Built: 1926

Architect: Trumbauer / Abele

Status: Standing as of August 2010

Built as the Science Building for the Women's College, the building was renovated in 1969 to become the home for the Duke University Museum of Art. In 2004, the collection was moved to the Nasher Museum, and the building was again renovated to house "Cultural Anthropology, Literature, African and African-American Studies, Latino/a Studies, Critical US Studies, and the Duke Human Rights Center."

Friedl Building, 08.25.10

Location of Friedl

Giles

Built: 1926

Architect: Trumbauer / Abele

Status: Standing as of August 2010

Named for three sisters (Theresa, Mary, Persis) who were the first women graduates of Trinity College (in 1878.) It serves as a dormitory.

August, 2010

Location of Giles

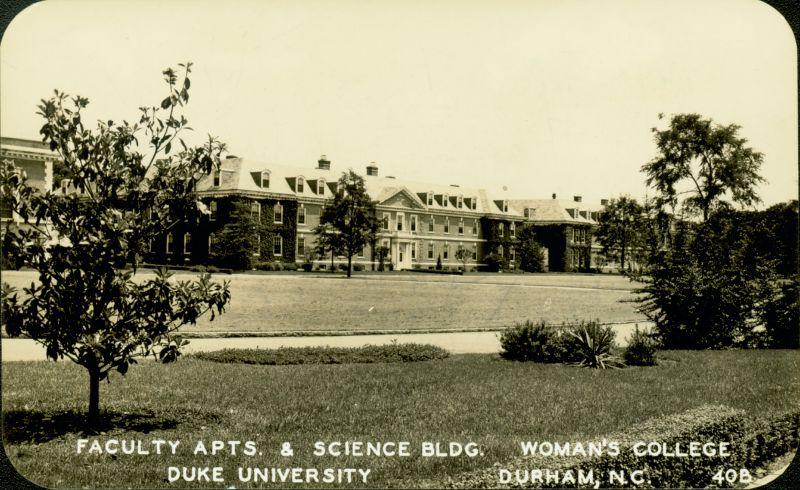

Faculty Apartments / Wilson

Built: 1926

Architect: Trumbauer / Abele

Status: Standing as of August 2010

The original faculty apartments on the Women's College campus, the building later became a student dormitory, and was reamed for Dean Mary Wilson in 1970

08.25.10

Location of Wilson

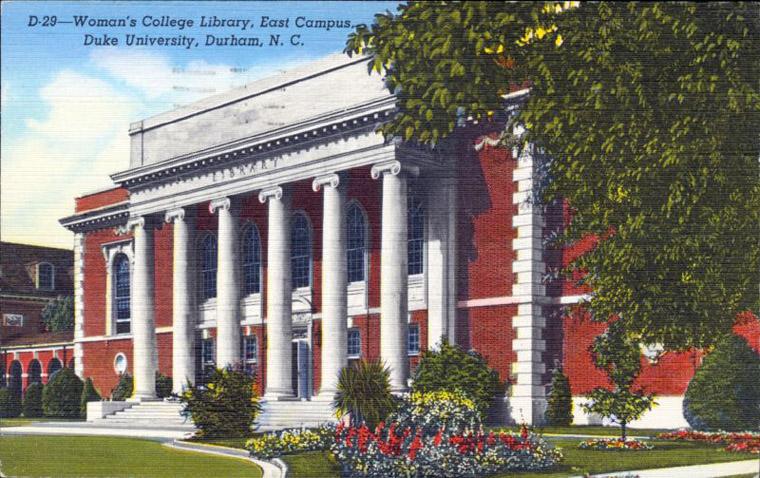

East Campus Library / Lilly Library

Built: 1926

Architect: Trumbauer / Abele

Status: Standing as of August 2010

Replacing the Trinity College Library, the East Campus Library also served as Duke's first Art Museum until the Science Building was renovated in 1969 for that purpose. It was renamed the Lilly Library in 1990 for donor Ruth Lilly, and underwent extensive interior renovation in 1993.

August, 2010

Location of East Campus Library

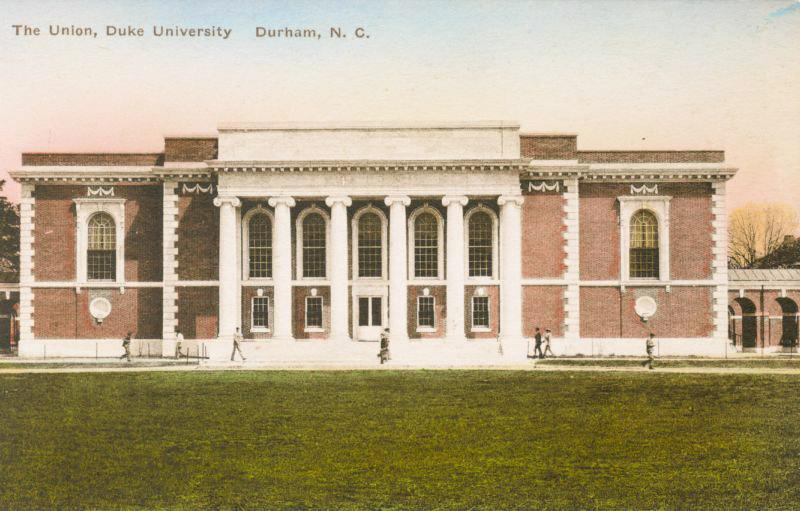

Union

Built: 1926

Architect: Trumbauer / Abele

Status: Standing as of August 2010

The original Union / dining hall for the Women's College, the the building contained multiple meeting areas and lounges, as well as faculty dining areas. As a small note that seems lost to the annals of time, when I was an undergrad in the late 1980s, there was a fine dining restaurant that accepted 'points' (on the Duke card) in the Union called the "Magnolia Room." The building is now called 'The Marketplace' since an major interior renovation in 1995.

08.25.10

Location of East Campus Union

Alspaugh (Second)

Built: 1926

Architect: Trumbauer / Abele

Status: Standing as of August 2010

One of the original numbered dormitories, the dormitory was renamed for Colonel Alspaugh (class of 1855,) as the North Dormitory on Trinity's campus had been earlier.

August, 2010

Location of Alspaugh

Brown

Built: 1926

Architect: Trumbauer / Abele

Status: Standing as of August 2010

One of the original numbered dormitories, the building was re-named for trustee Joseph Brown, class of 1875, sometime between 1927 and the mid 1960s.

08.25.10

Location of Brown

Pegram

Built: 1926

Architect: Trumbauer / Abele

Status: Standing as of August 2010

A dormitory, the building was named for Professor William Pegram

August, 2010

Location of Pegram

Bassett

Built: 1926

Architect: Trumbauer / Abele

Status: Standing as of August 2010

A dormitory named for Professor John Spencer Bassett, most well-known for the 'Bassett Affair"

Location of Bassett

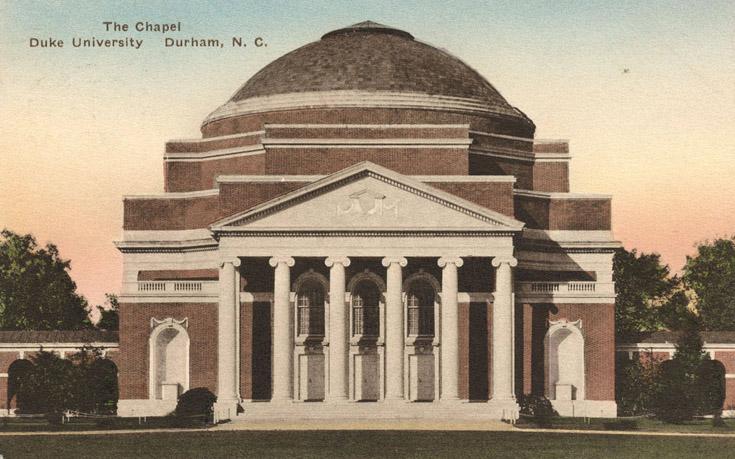

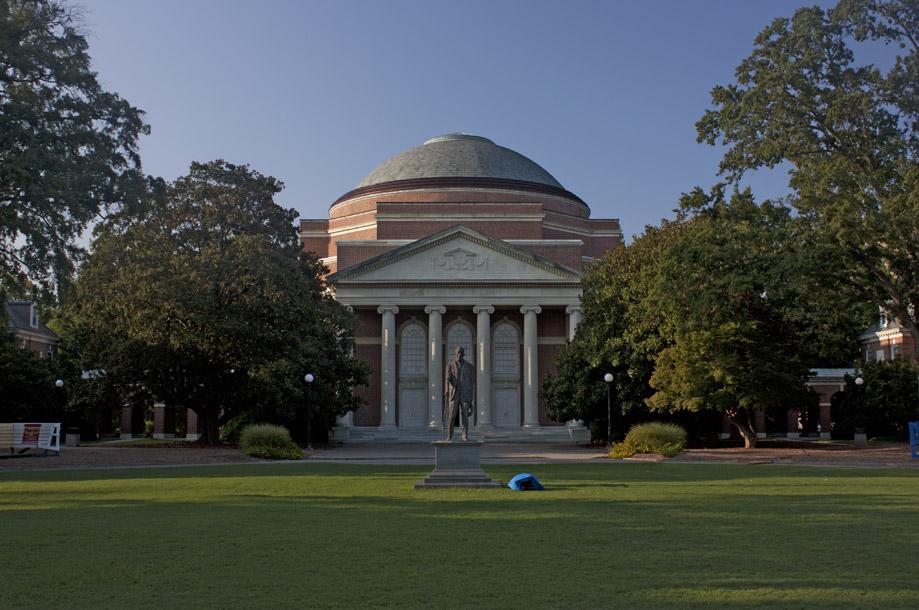

(Baldwin) Auditorium

Built: 1926-7

Architect: Trumbauer / Abele

Built as the focal point of the Women's College, the Auditorium was designed to sit 1400 people and was used primarily as a chapel for the college when it opened in 1927. The building is named for Alice Baldwin, who was a professor of history at Trinity, the first female faculty member at Duke, and first dean of the Women's college.

08.25.10

August, 2010

Location of Baldwin

Gilbert-Addoms

Built: 1957