From Nash's NC Architects entry:

Arthur Cleveland Nash (October 21, 1871-September 26, 1969), a Beaux-Arts trained New York architect, designed many buildings in North Carolina and is best known as campus architect for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill during the school's major expansion in the 1920s. There he worked in association with the consulting firm of McKim, Mead and White and engineer Thomas C. Atwood, with whom he formed Atwood and Nash, Architects and Engineers (see Atwood and Nash). Among Nash's major works were the Beaux-Arts Louis Round Wilson Library, with William Kendall of McKim, Mead and White, and the Georgian Revival Carolina Inn. He did much to establish the "colonial" mode as the predominant style for the campus and for Chapel Hill, setting a precedent that was followed well into the 1950s and readapted after a lapse.

Arthur Nash was born in Geneva, New York, the son of Francis Philip Nash, Professor of Romance Languages at Hobart College and Katharine Cleveland Coxe Nash, daughter of the Right Reverend Arthur Cleveland Coxe, Episcopal Bishop of Western New York. After attending Philips Exeter Academy, Nash graduated from Harvard, class of 1894. He spent a year at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and then left for Paris and the Beaux Arts Institute. Here for five years he studied in the atelier of Jean Louis Pascal. He received medals in architecture, archaeology, and modeling and was awarded a diploma in 1900. Returning to the United States he taught briefly at Cornell University in the School of Architecture and then moved to New York City to practice architecture. There he designed houses in New York and New Jersey and a clubhouse in Greenwich, Connecticut, and began his collegiate work with a gymnasium and science building for Hobart College and a dormitory for Smith College.

In 1922 his work began for North Carolina. He later told the story that one day when he was walking down Fifth Avenue he encountered William M. Kendall, a principal of the New York firm of McKim, Mead and White, which had recently taken a large commission to expand the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. Kendall said that the firm needed to send an architect to serve on site and asked Nash if he was interested. Nash promptly accepted. He and his family moved to Chapel Hill, where he spent the rest of the decade as building architect for the university in association with engineer Atwood, with Kendall representing the consulting firm of McKim, Mead and White and visiting the campus at intervals.

Nash found in Chapel Hill a small but rapidly growing university with classically detailed and Italianate style buildings dominating the original campus, which focused on the old quadrangle now known as McCorkle Place, stretching from Franklin Street and the village of Chapel Hill on the north to Cameron Avenue on the south.

Planning and construction for the expansion of the campus had already begun. Urban planner John Nolen had been hired in 1913 to help develop a master plan for the university. Between l917 and 1919 he analyzed the campus and suggested development of land to the south with a plan centered on a second, southern quad. Execution of his ideas was delayed by World War I and by the death of university president Edward Kidder Graham in the influenza epidemic of 1918. After the war with a jump in enrollment, a successful state bond issue, and the leadership of the new president, Harry Chase, work got underway. A "Trustees' Building Committee" of powerful alumni and state leaders played an important role throughout the long and complex project, with banker and university benefactor John Sprunt Hill of Durham as chair from 1924 to 1931. Another important contributor to the building program was the Faculty Committee on Grounds and Buildings, chaired by Professer William C. Coker. An initial building in the new quadrangle, Steele Hall, a Federal Revival dormitory, was completed in 1920 from designs by Raleigh architect James A. Salter..

As noted by Charlotte V. Brown in Architects and Builders in North Carolina, university leaders considered several nationally prominent architectural firms before choosing McKim, Mead and White in 1920. The university had also obtained recommendations from Aberthaw, an Atlanta engineering and campus planning firm, which suggested the placement of classroom buildings near the center of the campus expansion and dormitories at the periphery, types of plans for dorms, and the general red brick "colonial" style as well suited to North Carolina. McKim, Mead and White and the committee developed Nolen's plan and Aberthaw's suggestions still further.

To handle the large and complex project the university established in 1921 a professional engineering and architectural team in residence, headed by Thomas C. Atwood, an experienced New England engineer known for his ability to carry through large projects. Atwood, recognized nationally for the immense stadium known as the Yale Bowl, was in North Carolina as engineer for an expansion of the Durham Hosiery Mills before being employed by the university as "executive agent" of the building committee who was to "develop his own organization and . . . administer the whole work." The "T. C. Atwood Organization" included additional engineers, draftsmen, and an architect--initially H. P. Allen Montgomery who was succeeded by Nash in April, 1922. Atwood's organization worked under the guidance of the university committee and McKim, Mead and White. The general contract for the immense project went to T. C. Thompson of Charlotte.

By the time Nash arrived in 1922, several buildings were already underway. The South Quad (known today as Polk Place) had been begun as the focal point of the South Campus, and the red brick Georgian Revival style was well established. H.P. Allen Montgomery, Nash's predecessor as building architect, had designed several Georgian Revival buildings including classroom buildings (Manning, Saunders, and Murphey) defining the eastern side and cross-axis of Polk Place. (The western cross-axis has a similar ensemble designed by Nash's successor Weeks in the 1950s.)

Among the first campus buildings for which Nash served as architect were Bingham Hall at the southeast corner of the South quadrangle and Venable Hall. Beyond the main South Quad, as suggested by Aberthaw's study, were dormitory quadrangles known as the upper and lower quads, which continued the established style. Montgomery had previously designed Ruffin, Mangum, Manly, and Grimes Halls (1921) in the Upper Quad, and Nash planned Aycock, Graham, Lewis, and Everett Halls (1924-1933) in the Lower Quad (see Lower Quad Dormitories). All have a sense of open space between them and a well-proportioned layout. Nash also designed Spencer Hall (1924), the first women's dormitory, in the form of a large and imposing Georgian Revival house, on a large lot facing Franklin Street.

In the late 1920s, Nash focused special attention on the two edifices that defined the ends of Polk Place. South Building at the southern end of McCorkle Place, was an austere brick building built between 1798 and 1814 at the ridgeline that divides the north and south campuses. President Edwin Alderman had enriched it on the north front with a doorway copied from Westover in Virginia, as well as adding a temple cover to the Old Well in front of it. Beginning in 1926, Nash rebuilt the interior from the ground through the roof and changed the roofline, but his major contribution to South Building was a portico of four Ionic columns added to the south face of the building in 1927, creating an imposing façade that dominates the north end of Polk Place.

At the other end is the Louis Round Wilson Library, the "crowning glory" of the building campaign, with its six-columned Corinthian portico and great round dome. Reports of the time stated that the library was designed by Atwood and Nash, with the McKim firm consulting, and it was indeed a collaborative work. The idea of the dome and the detailing on this building are generally credited to Kendall of McKim, Mead and White: the firm had designed the much-acclaimed Low Library at Columbia University with its great dome, and at Carolina the dome was repeated. The overall design, especially the layout, was the work of Nash. Nash gave credit for the building to Kendall, especially for the detailing, but drawings by Nash (see John V. Allcott, The Campus at Chapel Hill: Two Hundred Years of Architecture (1986), p. 70) indicate his role as well. The limestone exterior contrasts effectively with the surrounding red brick buildings. On the interior is a series of elegant spaces with beautiful detailing--reading and reference rooms, an ornamental stairway, all well lit and beautifully furnished. When completed in 1929 the library was acclaimed the most beautiful building on campus and perhaps in North Carolina.

Beyond the south quadrangle, Nash designed the Kenan Stadium and Kenan Stadium Field House to the east of it in 1927. The stadium designed in Greek style had seats on the hillsides on either side of a creek (which flows beneath the field) in a park like setting, while the field house at the end of the field was in a contrasting Spanish Colonial style with a colorful red tile roof. (In recent years the stadium has been much enlarged and changed and the field house has been razed.) Nash also added buildings to the older part of the campus. Facing McCorkle Place Nash designed Graham Memorial Building (1929-1931) as a student center erected in memory of president Edward Kidder Graham. In 1930 he developed a proposal (see Allcott, Campus, p. 73) to provide a formal approach to the northern end of the campus. The envisioned Georgian Revival structures would have faced Franklin Street with a new Memorial Hall in the center; the Graham building on the left (east), and another similarly designed building to replace Frank Pierce Milburn's Battle-Vance-Pettigrew Hall on the right. The stock market crash and the Great Depression halted these plans, and only the Graham Building came to fruition: it lacked Nash's projected wings. Nash's Memorial Hall, a Beaux-Arts classical composition with front colonnade, was erected west of South Building on the Cameron Street site of its predecessor, the massive and eccentric Victorian edifice designed by Samuel Sloan.

Nash also extensively renovated several of the older buildings on and near McCorkle Place, including the two oldest buildings on campus, Old East (1793-1795, James Patterson, Alexander Jackson Davis) and Person Hall (1795-1798), as well as William Nichols's Gerrard Hall (1822). He also worked on Old West, New East and New West and planned the 1930 conversion of Frank Pierce Milburn's Carnegie Library into Hill Hall as the Music Building with auditorium added. One of the most interesting buildings on campus is the Playmakers Theater, originally known as Smith Hall. Designed by Alexander Jackson Davis, the temple-form structure was built in 1850 as a ballroom, which the students wanted, with shelves added to make it a library, which pleased the faculty. Under Nash the neoclassical structure became in 1924-1925 a theater for the university's emerging Playmakers group. (See Powell, First State University, p.177, for the interior remade into a theater.) As a result of these "renovations," all that is original of the pre-1860 campus buildings (except Smith Hall) is the brick walls.

Nash's commissions in North Carolina extended beyond the university. By 1924 he and Atwood had formed a partnership called Atwood and Nash, Inc., Architects and Engineers, with offices in Durham and Chapel Hill. (Atwood later partnered with H. Raymond Weeks as Atwood and Weeks, and in some cases there is ambiguity over which firm was responsible for specific projects, especially those that continued over several years.)

Nash had an especially strong influence on the growing community of Chapel Hill. A community landmark, the Carolina Inn, built in 1923-1924 adjoining the campus, has been extensively renovated and enlarged over the years but the fundamental design remains Nash's. It was conceived and sponsored by John Sprunt Hill, an alumnus and major benefactor of the university. After financing the structure, in 1935 Hill donated it to the university. The dedicatory plaque reads "This generous gift affords a cheerful inn for visitors, a town hall for the state, and a home for returning sons and daughters of alma mater." Nash's design brought to fruition Hill's dream of an inn that resembled Mount Vernon with its long portico, cupola, and roof balustrade. The inn continues to serve as a meeting place and hostelry for friends of the university and was dubbed by former university president William Friday "the University's Living Room."

Also in Chapel Hill, Nash is credited with the design of some of the fraternity houses built immediately west of campus, something of a new building type in the 1920s, which he planned as oversized Georgian Revival residences in red brick with large or small porticoes. Subsequent fraternity houses in the area followed Nash's precedent. Nash also advocated the red brick "colonial" style for Chapel Hill's commercial district along Franklin Street, as having the "dignity, repose and cultivation" appropriate to a scholarly town, and many merchants incorporated the style as translated into a "Williamsburg" mode into their store fronts. He also designed several private residences in town including his own home, the Nash-Wallach-Kalo House at 124 S. Boundary Street. When Chapel Hill resident Cornelia Spencer Love developed her own plans for her residence on Laurel Hill Road, she wanted to have her plan approved by Atwood and Nash; she later recalled that a draftsman for the firm made the blueprints for her and "Mr. Nash himself added curving tips to the roof and a small porch which greatly improved the appearance."

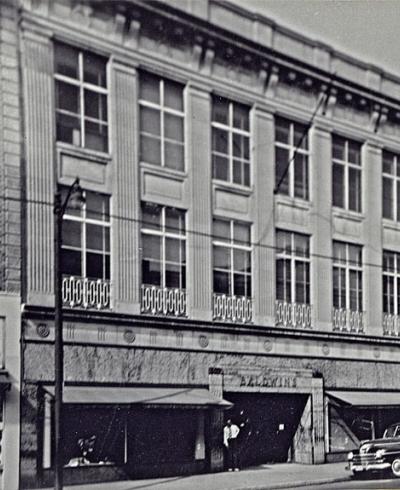

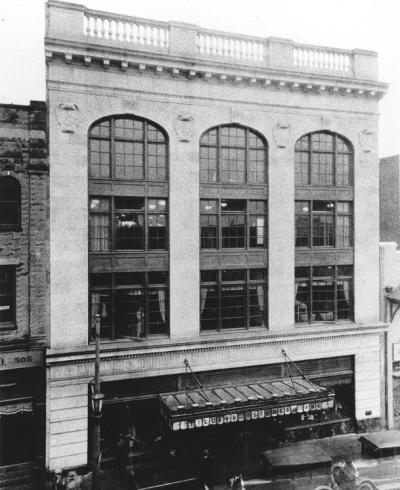

In Durham, just a few miles from Chapel Hill, Nash planned several public and private edifices in a variety of revival styles. For the Durham Fire Training Tower, where firemen practiced their firefighting techniques, he created a carefully proportioned structure akin to Giotto's tower in Florence: though without the sculptural decoration or varied colored marble, it features the paired openings of Giotto's tower, and the circular windows copy those of the Florentine cathedral next to the tower. At Watts Hospital ( begun in 1908 by Kendall and Taylor of Boston), the Valinda Beale Watts Pavilion added by Atwood and Nash in 1926 followed the facility's established Spanish Mission style with Renaissance detailing. For Durham's Old Hill Building (1925), Atwood and Nash employed a restrained Renaissance mode, with arched windows rising through the upper three stories and cartouches with John Sprunt Hill's monogram.

In their largest project in Durham, Atwood and Nash employed their traditional red brick Georgian Revival style when they were commissioned to design a new campus ensemble for present North Carolina Central University, which was growing rapidly under the leadership of President James E. Shepard. In 1925 the private school established in 1909 became the state-supported North Carolina College, the nation's first state-supported liberal arts college for black students. Funds from the state and from Durham philanthropist Benjamin N. Duke supported a major building campaign. Completed by 1930 were the formal, classically detailed Clyde R. Hoey Administration Building, the Alexander Dunn Hall, and Annie Day Shepard Hall. Subsequent buildings erected with New Deal funding continued the vocabulary established by Atwood and Nash. The firm also planned a number of public schools in and near Durham.

In Raleigh, the firm gained several prominent commissions, and here too they followed Beaux-Arts principles, employing a variety of revival styles to suit different situations and to harmonize with the setting. For the Revenue Building facing the State Capitol, they continued the capitol square's established vocabulary of restrained Beaux-Arts classicism rendered in pale gray stone to complement the 1840 Greek Revival capitol. In new buildings at Peace College, the firm used the red brick Georgian Revival mode to harmonize with the antebellum main building by Thomas J. Holt and Jacob W. Holt. Atwood and Nash also planned renovations and restoration work at such Raleigh landmarks as the North Carolina State Capitol and the Executive Mansion. Nash designed a number of houses in Raleigh, primarily in Georgian Revival style. Notable among these is the stately red brick Jolly-Broughton House (1928) built for Mrs. Frank Jolly in the Hayes Barton suburb and later the home of Governor J. Melville Broughton. For Episcopal bishop Joseph B. Cheshire he designed the white frame Cheshire House with a tall portico, located in the Cameron Park neighborhood.

A departure from sober classicism came with the festive and eclectic design for the State Fair, an institution newly relocated on a site west of Raleigh. In the State Fairgrounds Exhibition Buildings Atwood and Nash presented a lively combination of Spanish and Moorish motifs, so that when the new fairgrounds opened in 1928, fairgoers entered through paired gates flanked by towers, piers, and twisted columns. Red tile roofs and stuccoed walls completed the ensemble.

Beyond the Piedmont, as noted in the Asheville Citizen of October 22, 1929, Atwood and Nash opened an office in the booming mountain town of Asheville, with architect Lindsey M. Gudger as local manager; Asheville was soon hit hard by the Crash, however, and the office closed. A key work in the city was the lavish Tudor Revival style John Sprunt Hill House in the Biltmore Forest suburban village developed near Asheville on a portion of the Biltmore estate. At the other end of the state, Nash employed the Georgian Revival mode for the Alexander Sprunt House (1929-1930), built in Wilmington for a relative of John Sprunt Hill.

In 1930 Nash retired and moved to Washington, D. C., but he continued until 1953 as consulting architect to H. Raymond Weeks, who became the university architect at Chapel Hill, and in that role contributed design ideas for a such later university buildings as the public health and medical building, Woolen Gymnasium, Bowman Gray Swimming Pool, and Lenoir Hall. He also helped plan several new dormitories--Alderman, Stacy, McIver and Whitehead--as well as working on Wilson Hall and the women's gymnasium. With local architect Archie Davis he served as consultant for the naval armory and Navy Hall (later the Monogram Club). He also served as consultant for portions of the North Carolina Memorial Hospital complex and additions to the Carolina Inn, Wilson Library and Venable Hall. Meanwhile, Thomas C. Atwood had formed a partnership with architect Weeks, known as Atwood and Weeks, which moved to Durham in 1931 and planned many major buildings in the state.

The North Carolina Chapter of the American Institute of Architects wanted to nominate Nash for consideration as a Fellow, especially for his work on Wilson Library, but Nash turned down the honor. He felt that others also deserved credit for his work, citing as an example William Kendall, chief representative of McKim, Mead and White, who Nash said had done much of the detailing of the library. At the June 1954 commencement in Chapel Hill, Nash was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws degree.

At Grace Episcopal Church in New York on August 12, 1914, Nash married Mary Screven Arnold, a distinguished portrait painter. They were parents of a daughter Katharine Cleveland who married Edward E. Caldwell. Nash died at the Caldwell home in Baltimore and was buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Note: The building list includes Nash's best-known works but not all of the many residences and other structures he designed. Further research will identify more of these. Renovations and restorations and consulting projects are cited in the text but do not have separate building entries unless they are included in building lists for the architects of record such as H. Raymond Weeks. For a more extensive listing of projects by Atwood and Nash and Atwood and Weeks, see Atwood's "Cubic Foot Costs Book," Special Collections Research Center, NCSU Libraries, Raleigh, North Carolina.

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.