Over Halloween weekend of 2009, Preservation Durham offered its second annual Ghost [building] Tour. That tour, in part inspired by the description in Endangered Durham of lost structures throughout downtown, invited participants to experience -- in situ -- historic streetscapes of downtown Durham.

While standing in the location of the original photographer, tour participants viewed semi-transparent photographs of homes and businesses, churches and civic institutions, and saw contemporary life peeking through. None of these buildings remain (hence, their "ghost" status); parking lots cover most of the parcels formerly occupied by these structures.

Excerpts from the tour booklet are listed below, along with the individually profiled Endangered Durham features.

BEFORE BRIGHTLEAF AND WEST VILLAGE

One hundred years ago, the part of downtown Durham between what we currently call Brightleaf Square and West Village was firmly held in Duke hands. Not Duke University, which had only recently been relocated from Randolph County fewer than twenty years prior and which was still known by its erstwhile name of Trinity College, but rather by the Duke Family.

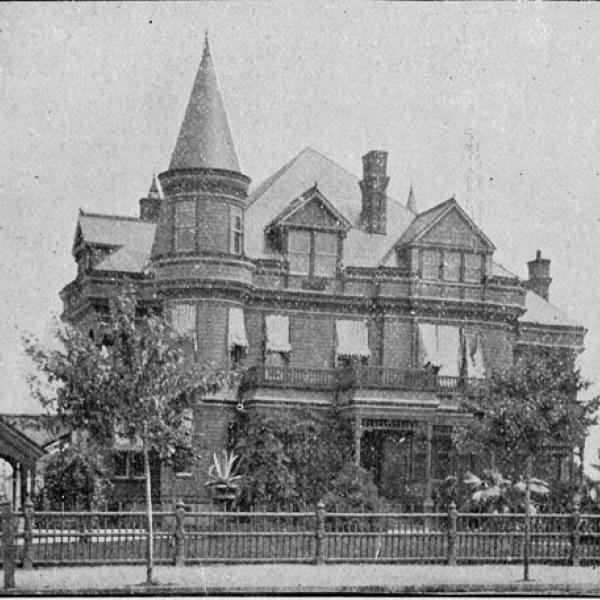

In 1909 Fairview, the Victorian mansion of recently deceased patriarch Washington Duke, stood at the southeast corner of Duke and Main Streets. Two of Wash’s three adult sons built their own homes nearby: Brodie lived a large house (where the Durham School of the Arts is now located), complete with a four-story tower on its front façade; Benjamin had recently erected Four Acres, a spacious, Chateauesque mansion on the southeast corner of Duke and Chapel Hill Streets. The Terrace, his earlier Victorian mansion, had been moved to the north directly across Chapel Hill Street.

Buildings of the Duke’s American Tobacco Company empire book-ended this area, with the Old Cigarette Factory on the east (although it was, in 1909, four stories tall) to the new Watts and Yuille warehouses to the west. The Main Street Methodist Church, built for the religious care and education of the factory workers, stood at the southeast corner of Gregson and Main Streets.

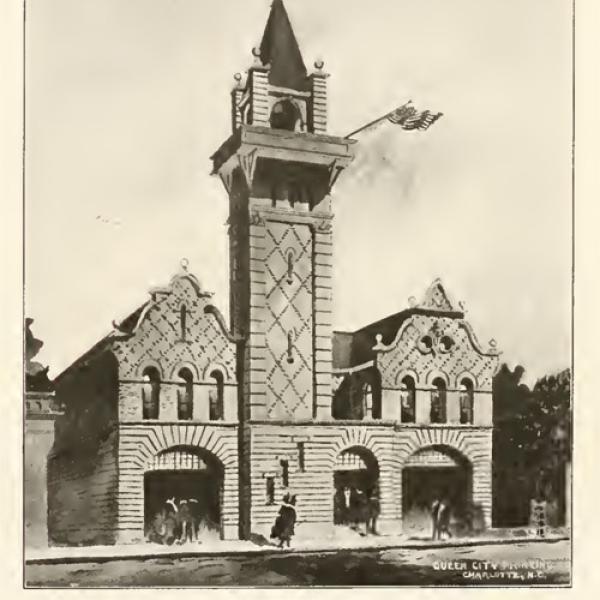

Other cultural amenities and civic services provided by the Dukes dotted the landscape: Brodie gave land at the northwest corner of Duke and Main Streets for a picnic and playground area, while Ben and Wash financed the beautiful Italianate Southern Conservatory of Music. Additionally, the family company built the City’s second fire station, one block east on Main Street. Even the street names reflect the influence of the family: Duke, Fuller (their legal counselor), Memorial (honoring both Wash and daughter Mary), and Gregson (the family’s pastor at Main Street Methodist).

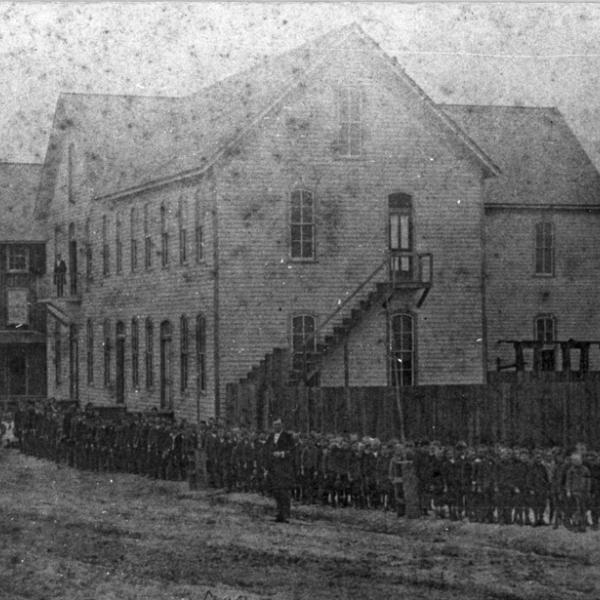

Yet the seemingly unbreakable bond between Duke and Durham was not assured from the outset. Washington Duke, who moved his family to the very western edge of town in 1874, was just one of many tobacco growers and peddlers in the area. Longtime nemesis William T. Blackwell, owner of the “Old Bull” smoking tobacco brand, built his own house in 1875 at the northeast corner of Duke and Chapel Hill Streets, a stone’s throw from Wash. A few years later, Blackwell was a driving force in sustaining Durham’s first public Graded School, which opened across the street from the Old Duke Cigarette Factory.

Two other buildings on this tour were constructed in the 1920s: the Durham Dairy Products building and the YWCA. These structures went up as the Duke family interests were shifting toward hydroelectric power and in endowing Trinity College.

The ghosts of the past are within reach, as you will see on today’s tour. The area between Brightleaf Square and West Village was once populated with the homes and civic establishments of the Duke family, as well as others. Learn their stories; gaze at their photographs. And consider what life was like, here, at a different age.

Comments

Submitted by scott mitchell (not verified) on Thu, 11/8/2012 - 2:36pm

Back in 2009 I took the Durham Preservation Society walking tour called 'Ghost Buildings of Durham'. Our tour guide had some laminated photos on a clipboard. One of them was of the Hotel Carrolina. It was not the one featured on this website. In the photo he had, the entire staff of the hotel was lined up on the steps and veranda in uniform. I'm trying to get a copy of that photo. Any ideas how I might go about it?

Submitted by gary on Thu, 11/8/2012 - 3:13pm

http://www.opendurham.org/buildings/hotel-carrolina?full

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.