The Lustron house is a quirky branch on the evolutionary path of mass housing production in the United States during the mid-20th century. I'm not an expert on this topic, and there are entire websites devoted to Lustron fandom out there to peruse.

Various attempts to mass produce housing in the US date back to at least the first decade of the 20th century, with the advent of 'kit' houses - which, as the name implies, were ordered from a company and shipped disassembled, but with all parts pre-cut and in sufficient quantity for a local builder to erect a complete house.

Sears houses are the most well known of these, but a quick Wikipedia glance lists 11 major companies.

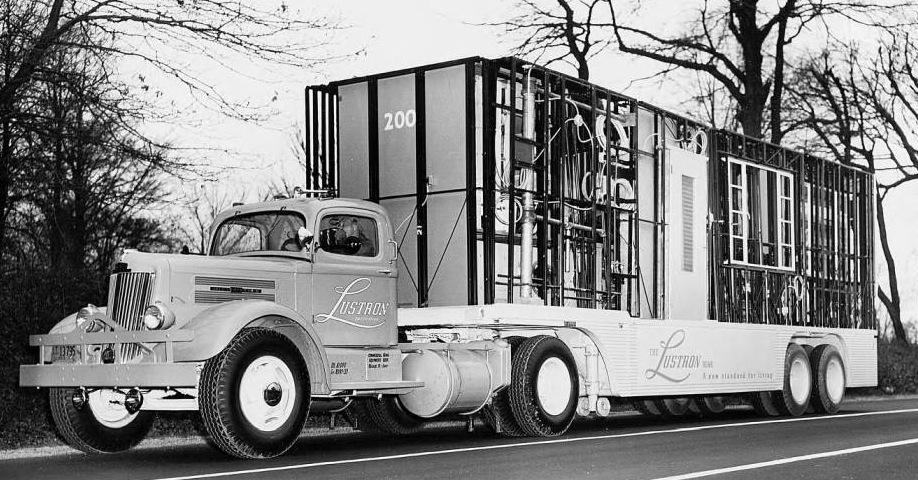

Kit houses waned in popularity after World War II, and the great infatuation with industrial mass production along with widening highways, etc. gave rise to several efforts to more fully assemble houses at a central location and ship them in assembled or partially assembled form. The evolution of these efforts exist today as mobile homes, modular houses, and pre-fab(ricated) houses.

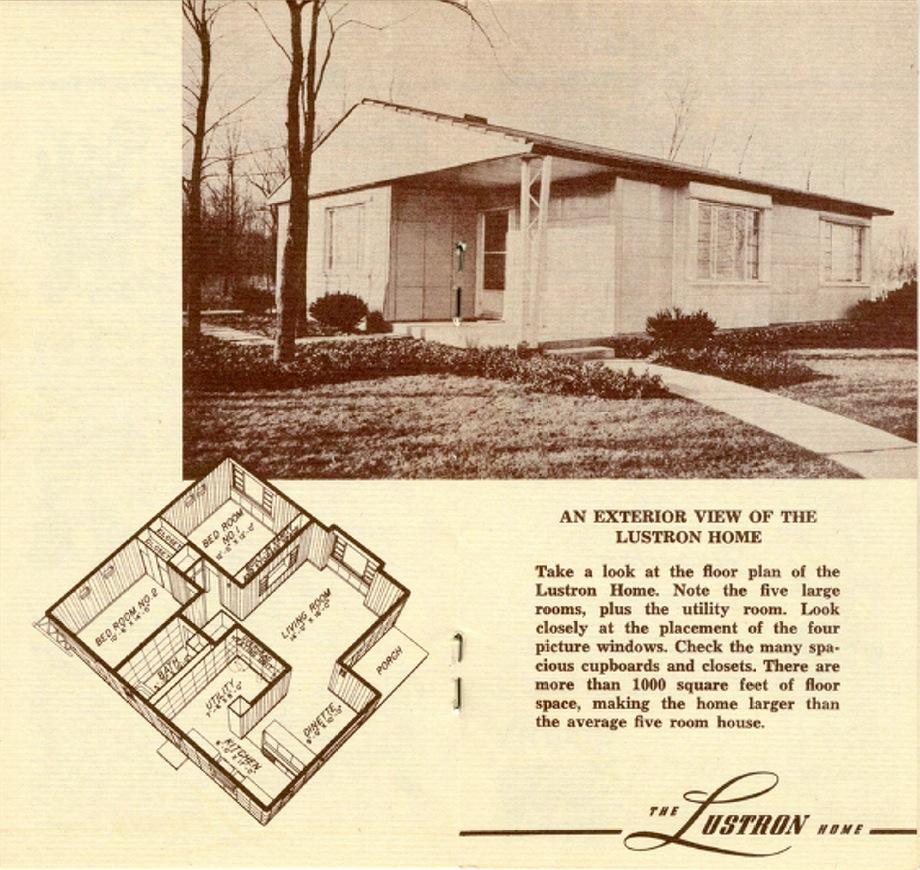

Lustrons were an unusual product, taking cues from the appliance and automobile industries in material selection - the houses are steel framed, and interior/exterior finishes make heavy use of enameled metal panels - of the kind typical on mid-century appliances. There were several models to choose from, and a selection of colors.

Even the roof 'shingles' were enameled steel, and the interior came with built-in cabinets, pass-throughs, etc. - all in the same enameled metal.

The pre-fabricated sections of house would be shipped to the building site and assembled - typically on a concrete slab, but occasionally over a foundation that provided a basement.

The general idea behind prefabricated housing was the same idea that had dramatically shifted industry from craft / local to centralization. The advantages of scale production / and the plummeting cost of shipping would provide a cheap and predictable product. The combination of the predictable assemblage and 'low-maintenance' materials would provide a product that minimized future operating costs (both direct and indirect.)

No worries about painting, scraping, etc. Just hose it off.

In theory, this should have been a great idea.

Carl Strandlund was a Swedish-born engineer who had worked for the Chicago Vitreous Enamel Products Company, and helped to retool the company's factory to produce products for World War II. Near the end of the war, Strandlund devised and patented an architectural porcelain enamel panel : “The present invention relates generally to architectural porcelain enamel panels, but more particularly to a novel and improved construction and an arrangement of interlocking and sealing adjacent porcelain enamel panels, units, or adjoining connecting parts of the exterior or interior walls of a building or structure of any type or design.”

After the war, Strandlund applied to the Reconstruction Finance Corporation for financing to deploy his architectural panels in the construction of gas stations_ but was denied. Seeing an opportunity in the government's concern over housing shortages for returning GIs, Strandlund persuaded the Federal government that the same techniques could be used to mass produce quality housing cheaply and efficiently. They were persuaded, and would eventually loan Strandlund $37.5 million.

In 1947, Strandlund formed the Lustron Corporation. He stated - “We believe that our technology has advanced to the point where a basic commodity as necessary as a home no longer should be handmade,” Strandlund said. “We think it has advanced to the rank of the automobile-that it can be mass-produced, handled by local dealers, transported to a new locality if desired, even traded in on a larger model.” He added: “The Lustron home isn’t a cheap house by any means. It isn’t a substitute for a house similar to those we are used to now. What Lustron offers is a new way of life.”

The Lustron Corporation utilized a 1 million square foot plant that had been used for manufacturing warplanes in Columbus, OH, and started with heady claims of volume production. The plant started with four house models in eight colors: "Surf Blue," "Blue-green," "Dove Gray," "Maize Yellow," "Desert Tan," Green, Pink, and White. The houses were designed by Morris Beckman of Chicago architectural firm Beckman and Blass

The plant fell behind the ambitious schedule almost immediately, and hopes that some 'parts' could be sold to other companies did not materialize. There are a multitude of theories as to why the Lustrons failed as a business model, but the internet consensus seems to be some combination of overly ambitious goals in devising an entirely new way of building and commoditizing a product that had antecedents, but was new and different looking, along with a new distribution network. Perhaps most importantly, people seem to see houses differently than other consumer products. Even if a house is the blandest pseudo-traditional, repetitive plasticness in a subdivision, people will still pay top dollar while turning up their noses at modular or mobile homes as inferior.

Houses were also something with a well-established local production industry in almost every city and town. Whether that industry could meet volume or not, it was competition - unlike refrigerator production or similar. Various levels of credence are given to the role that resistance from local contractors and government played in hampering acceptance of Lustrons.

By 1950, the company was bankrupt, having produced ~2680 Lustron houses. The houses were mostly deployed on the east coast. Lombard, IL had 120 houses. The US Government installed 60 at the US Marine Corps base at Quantico, VA.

Durham still has 5 Lustrons - various online directories list one more - at the Broad Street address of Marie Austin Realty, where it clearly isn't. So there may be another out there somewhere.

Comments

Submitted by H.T.Buchanan (not verified) on Mon, 12/5/2011 - 5:55am

I, Googled Lustron homes and found an image of 1204 Broad St. the home is the 2120 Sprunt St. home.

Submitted by Toby (not verified) on Fri, 12/30/2011 - 3:10pm

I wonder how well wifi and other air-based communications work with all that steel in the walls.

Submitted by John (not verified) on Sat, 10/13/2012 - 8:22am

In reply to I wonder how well wifi and by Toby (not verified)

In my experience, I lived in a Lustron for years and had no issues with cell or WIFI.

Submitted by Kevin Hartzog (not verified) on Mon, 1/2/2012 - 11:17am

Thanks for the post. Kit homes remind me of the movie "One Week" with Buster Keaton. Modern styled premanufactured homes won't catch on until someone like Ikea or Apple (iHome?) sells one. I bet kids could have a lot of fun with refrigerator magnets in a Lustron home. I know some offices with metal demountable partitions where people are using the whole wall has a bulletin board. Wifi probably works okay since the Lustron home is small, however it is a little similar in construction to radio frequency (RF) shielding for an MRI room. RF travels well through horizontal panel seams. They usually have to stuff panel seams with bronze wool to stop RF in MRI rooms.

Submitted by Deborah (not verified) on Fri, 5/18/2012 - 5:01pm

Just came across the comments on this section. Wireless works fine overall but 2120 does have some quirks that service providers are quick to blame on the house. Overall it's pretty terrific. Re 'Lustrons are interesting because they sought to address two areas little addressed by green building, the Movement - durability and portability. It's poor at addressing another weakness of most 'green' designs - user serviceability/inexpensive replacement/repair costs', I'd agree on durability and also expense of replacement/repair, but it must be said that over time they require far less in the way of 'replacement/repair' than most houses (see: 'built like a tank'). My 1949 roof as impenetrable as it was when soddered and sealed in the factory and porcelain enamel means never having to repaint, inside or out. So while the 'dealer' the serial plate advises owners to 'see for service' no longer exists to provide new rollers for sliding cabinet and pocket doors for example (a recurring issue for most lustron owners, I now know), it's hard to begrudge a bit of bother to get them reset once every half century or so, on balance. Personal note re prefab/context: I had started my search with prefab in mind and also worked through initial design phase for an architect designed house before stumbling across and ultimately deciding upon my lustron.

Submitted by AudeKhatru (not verified) on Fri, 10/26/2012 - 1:43pm

I would love to know what Frank Lloyd Wright would have thought of these. I doubt he would have liked them, but the concept of the Lustron could have been used to build houses along the lines of his Usonian houses.

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.