Labor Temple, 1950s (Courtesy Herald-Sun)

In April 1941, the heirs of Mary A. Green - longtime resident of a home at this address who had bought the land from A. M. Rigsbee in the 1880s - sold this parcel to trustees of the Plumbers & Steamfitters Union, Local 585. By the next year, along with more than two dozen other 'locals' affiliated through the Durham Central Labor Union, they had finished this deep two-story building with dual storefronts facing Mangum. For more than three decades, the building - with its large second-floor meeting hall - provided offices and regular gathering space for thousands of unionized workers and their representatives.

Meanwhile, at the street level, the storefronts were home to a succession of businesses, part of a commercial cluster around Little Five Points. The D. W. Brown Dry Cleaners pictured at 705 (the left bay) above was a branch of a business that had begun on Driver Street in East Durham in the 1930s. Next door at 707, "Atlas 5c to $1.00" department store sold its variety of wares through the mid-1950s. A change in management - and apparently some price inflation - saw the space rebranded as "Marion's 5c to $5.00 Store" from around 1955. By the end of the 1950s, however, commercial tenants seem to have left. A pool hall followed a short-lived watchmaking school at 707 from 1962 - appropriately named Union Billiards.

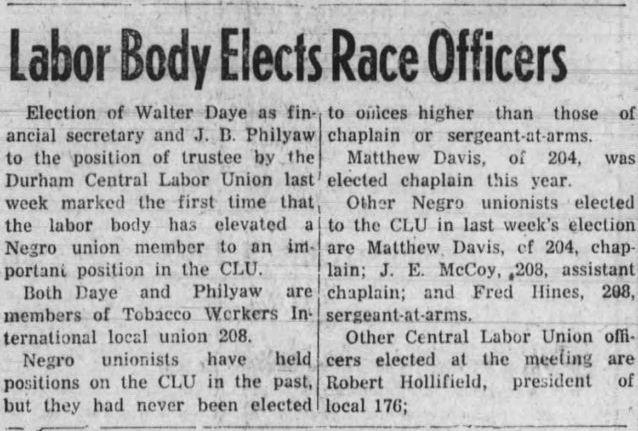

The segregation of the labor movement in Durham is a subject for more detailed study, but it appears that many of the 'locals' based here represented white workers. African American union groups appear to have met in a separate Labor Temple on Pine Street (which later became South Roxboro). Ostensibly representing members of both races, the Durham Central Labor Union - operating out of headquarters in this building - began to elect African American workers to leadership roles in the late 1950s.

Clipping from a July 1959 issue of The Carolina Times marks the election of tobacco workers Walter Daye and J. B. Philyaw among the first African American officers of the umbrella Central Labor Union. (Available online via DigitalNC)

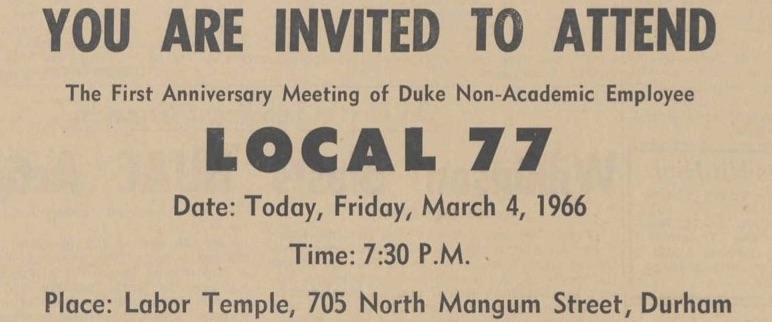

In the years that followed, the Labor Temple on Mangum remained a hub for organizing as the integration of the union movement accelerated. From the mid-1960s, it appears to have hosted gatherings of the nascent union for Duke's non-academic employees: a largely African American workforce.

Advertisement in The Duke Chronicle from March 1966 encouraging attendance of a Local 77 meeting at 705 N Mangum. (Full collection of the Chronicle available digitally via Duke Libriaries.)

A bit more about the group that gathered here to celebrate their first year is worth quoting from the same Chronicle ad:

Oliver Harvey, President of Local 77, has seen many changes in working conditions at Duke University since coming here in 1951. A janitor, Mr. Harvey started at 55c per hour. When Mr. Harvey came on the job, some employees were earning only 48c per hour. "I knew they were asleep," Harvey says. "I wondered why, and how they could be. I knew they were asleep and had to be awakened. I wondered how these people survived."

Duke non-academic employees are no longer asleep. Mr. Harvey's early efforts, with much help from faculty and students, have brought about many changes. Changes have come faster in the past year since the formation of the Benevolent Society in February, 1965, and its affiliation with a national Union in September. Much has been done; much remains to be done.

If you're wondering, "Who Was Oliver Harvey?" - you should read the February 2020 article about him from Scalawag. Long overlooked despite his crucial role in activism on campus and beyond, Harvey has gained overdue attention in several recent projects - including Durham County Library's Durham Civil Rights Heritage Project and Duke's Activating History for Justice.

Union successors sold the building in 1977, and information about its use over the next decade remains to be gathered. Interestingly, a large cache of Durham Central Labor Union documents seems to have been left for years in storage on the upper floor of the building. Fortunately, the new owners from the 1990s - St. Luke Apostolic Church of Jesus Christ - passed the collection on to archivists at Duke.

With this part of Durham rapidly transforming, the next chapter in the life of the former Labor Temple remains to be written. This building - entering its ninth decade - could be a key anchor in the revival of a community and commercial node at Little Five Points.

This building was the subject of a What's It Wednesday?! post on Open Durham's social media accounts (Facebook and Instagram), the week of March 17, 2021. Follow us and stay tuned for more finds!

UPDATE: Hundreds of people engaged, shared, and commented on the post about the former Labor Temple, expanding the story of this gathering space with personal memories and pieces of their family history. A few reached out to discuss in more detail, and we'd be thrilled to hear from more by email or in the comments below. A summary of these contributions (as of midday on March 18, 2021) is included below.

Marshall Clements worked for Owens-Illinois Glass Company in the 1960s, and was a member of the American Flint Glass Workers Union that met here.

Bonnie Meeks mentioned her father attending steamfitters union meetings here.

Jerry Phillips and his uncle – Bennie W. “Buck” Phillips, who ran Durham Window Cleaners – came here daily to keep it clean. Said Jerry of his uncle’s arrangement with the owners, “that was one of his accounts for over 25 years. We emptied the trash, ran a dust mop over the floors, cleaned the bathroom, and cleaned the windows on the outside.”

Rik Rasmussen’s mother worked at Liggett & Myers Tobacco in the 1950s and 1960s. Her union meetings were here.

Amelia Poppell also had a mother who worked for L&M. In addition to the Tobacco Workers Local meeting at the Labor Temple, she recalled the union owning a retreat outside of town – known as Lake Unity – that she enjoyed visiting from around 1965. “There was a concrete building there which housed a locker room and a snack area. You could shower and change clothes. It was a popular place to go during my teenage years. Lots of people there on the weekends.”

Bobby Page headed the United Food and Chemical Workers, Local 298 – representing coworkers with several regional offices of the Public Service Gas Company for 18 years in the 1970s-1980s. He recalled monthly meetings here on Thursday evenings, with members often coming in from as far as Roxboro and Henderson. As few as a dozen or as many as thirty would attend depending on the situation, in the upstairs meeting space he described as functional but far from fancy. Mr. Page was elected to replace a well-liked predecessor he felt had become too much of a “company man,” but on the whole remembers a decent dynamic between workers and management. For advocacy on the individual level, it was his role to help coworkers push for advancement up established levels of pay and responsibility. When it came to larger-scale, collective contract negotiations, UFCW sent in more experienced representatives to take the lead – not always with productive results. During his tenure, the Local simply used the space on N Mangum to gather, not for offices as other groups appear to have done (at least in earlier years according to city directories). Possibly when the Labor Temple was sold in the late 1970s, Local 298 began renting a room for the monthly meetings at the Gorman Ruritan Club on East Geer outside of town. Reconfiguration in the larger labor organization changed their affiliation at least once.

Doug Council described his father-in-law, journeyman electrician and member of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local that assembled here. From the late 1940s until retirement around 1983, “worked on power plants, factories, paper mills & the Fayetteville tire plant.”

Dana Davis shared that his father – Charlie Davis – worked as an instructor at the Carolina School of Watchmaking, which used occupied one of the first-floor storefront bays in the early 1960s.

Larry Sexton was a kid when his father, a brick mason, would come home after evening meetings for his union at this location.

Bobby Jones followed in family footsteps to meetings at the Labor Temple. In his words, “I was a member of ITU [International Typographical Union] local #125, as was my Daddy, W. O. (Wimpy) Jones, and all the other Composing Room (printers) employees of The Durham Morning Herald and The Durham Sun newspapers….I was active from 1973 to 1978. My Dad was active for over 40 years.” Mr. Jones grew up a short walk northeast on Edward Street, where his family lived next to the Fowlers, operators of the service station nearby at 701 N Mangum.

Candace Glass recalled that Retail Clerks Local 204 met here in the late 1950s and 1960s. This group was also part of union reconfiguration, she said, merging with a “Meatcutters union” under the same umbrella UFCW that incorporated gas company workers like Mr. Page above.

Jack Woodlief remembered the pool room that opened here from the early 1960s, and suggested this might have been the meeting location for City workers who unionized around that time.

Diana Ligets Bello added: “My dad and the original Greek men who immigrated and ended up in Durham held some kind of meetings there. I have a photo somewhere I’ll try to find.”

Comments

Submitted by Misspent Youth on Sun, 3/21/2021 - 9:59pm

Played many a game of pool in that pool hall when I was a teenager (Not really old enough) but I looked very mature for my age. Matter of fact I played in several pool halls in Durham (I remember the Brass Rail) and only got tossed out of one uptown. Owner asked for my ID and I told him I left it in my other pants. He didn't buy it and told me to get out...

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.