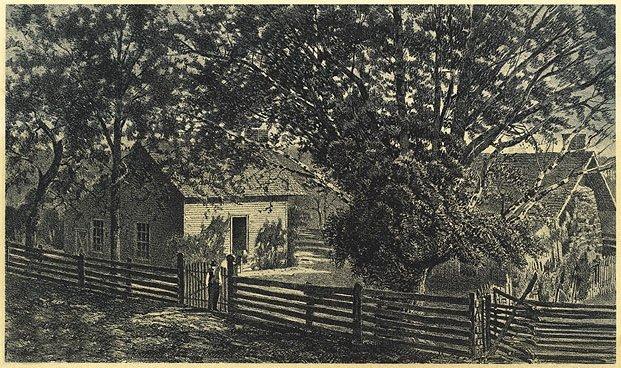

The farm the would become Bennett Place consisted of 325 acres when James and Nancy Bennitt settled on the farm in 1840. The Bennitts grew corn, wheat, oats, and potatoes, and raised hogs. Bennitt was also a tailor, cobbler, and sold horse feed, tobacco plugs, and distilled liquor.

In April, 1865, at the close of the Civil War, General Joseph E. Johnston (Confederacy) and General William Tecumseh Sherman (Union) met at the farmhouse of James and Nancy Bennitt to negotiate the surrender of Confederate forces in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. The surrender, formalized on April 18, 1865, was the largest of the four troop surrenders to end the Civil War (the others occurred at New Orleans, LA, ; Citronelle, AL ; and Appomattox, VA)

In the weeks leading up to the surrender, Sherman had completed his 'total war' March to the Sea. From Savannah, he turned north and began his 'Carolinas Campaign.'

General William T. Sherman advanced into North Carolina in early March, 1865, destroying the Confederate arsenal at Fayetteville, and, while keeping the Confederate army off-guard with several feints, moved toward Goldsboro, where supplies and additional troops awaited him, as well as control of the railroad at Goldsboro. He planned to then advance into Virginia to unite with General Grant. Johnston attempted to stop him at Bentonville, about 18 miles southwest of Goldsboro. This failed, and Johnston retreated to Smithfield, and then towards Greensboro.

When the news of Confederate defeats in Richmond and Petersburg reached Sherman on April 6, he prepared his 60,000 troops to march northward on April 10th. While still in Smithfield, news of General Robert E. Lee's surrender at Appomattox, VA reached the army, which allowed Sherman to abandon plans to advance to Virginia, and instead focus on the retreating army of Confederates under Johnston. Sherman asked the President for his direction on terms of surrender and the treatment of Confederate troops. Lincoln stressed "malice toward none, with charity for all."

Governor Zebulon B. Vance of North Carolina, seeking to avoid the destruction visited upon previous states Sherman had marched through, sent a peace delegation to Sherman offering to surrender the State upon his promise to help terminate hostilities and to recognize the State government. This proposal was evidently never addressed amidst the larger movement towards surrender and the end of the war.

Johnston also realized the situation was hopeless for the Confederacy and went to Greensboro to confer with Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his cabinet for two days. Davis wished to pursue a renewed Confederate offensive; however, when informed by Confederate Secretary of War John C. Breckenridge that Lee had surrendered at Appomattox, Davis empowered Johnston to offer terms of surrender to Sherman.

Sherman had entered Raleigh on April 13 without encountering resistance. Governor Vance had fled the city that morning. There, Sherman established his headquarters and made plans to advance to Asheboro and Salisbury or Charlotte. In the midst of his preparations, however, the letter came from Johnston asking for "a temporary suspension of active operations . . . the object being to permit the civil authorities to enter into the needful arrangement to terminate the existing war." Johnston proposed a meeting for April 17 and Sherman accepted. Sherman took a locomotive and train car to Durham's Station.

Johnston travelled east to Confederate Lieutenant General Wade Hampton's headquarters in Hillsborough with a detachment of the 5th South Carolina cavalry, where he set up headquarters at the Alex Dickson homeplace. Sherman had a train convey him and his party to Durham's Station, where he was greeted by Brigadier General Kilpatrick and a cavalry honor guard.

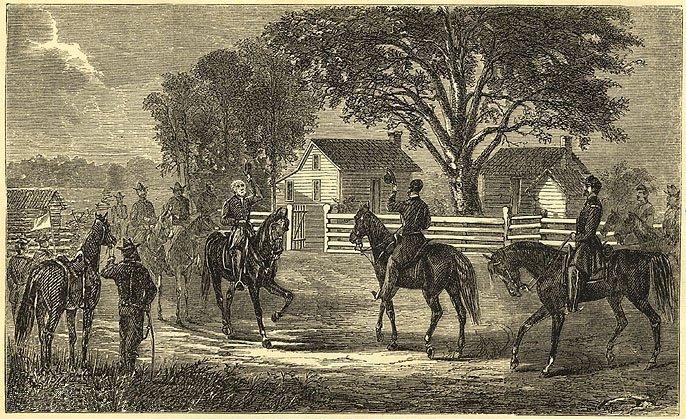

It is unclear how the Bennitt farm was chosen - some sources state that it was chosen ahead of time, as the midpoint between the two armies. This seems unlikely, unless someone with local knowledge specifically proposed it. What seems more likely is the history that suggests that, as they traveled east on the Hillsboro Road, General Johnston with Lieutenant General Wade Hampton met Sherman and the 9th and 13th Pennsylvania Calvary, riding west from Durham Station, on the Hillsboro Road, both bearing white flags. They shook hands while still mounted, and Johnston suggested to Hampton that they meet at a farmhouse that Johnston had just passed, and Sherman agreed. There is little record of how the Bennitts felt about their farmhouse being used for the surrender proceedings; having lost three sons in the war, one would have to believe that they had strong feelings about it one way or another.

Drawing of the Bennitt farmhouse and James Bennitt from Harper's Weekly, 1865.

Drawing of the meeting of Sherman and Johnston from Harper's Weekly, 1865.

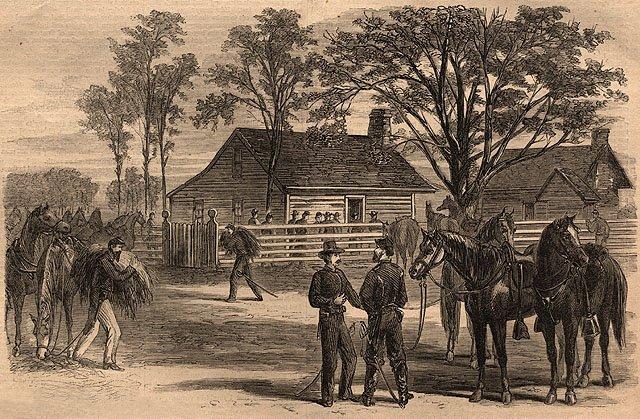

Drawing of the soldiers waiting during the conference from Harper's Weekly, 1865.

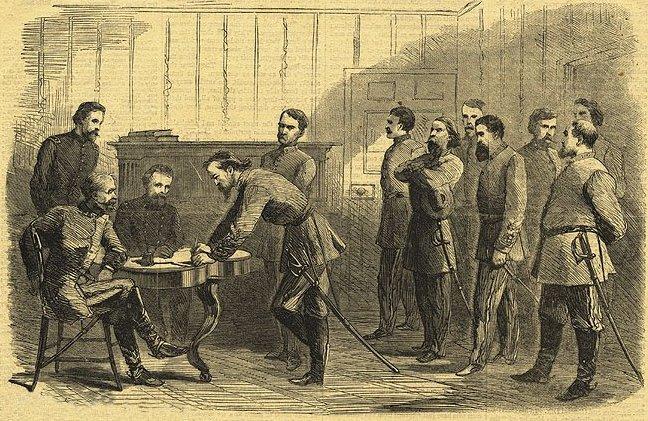

Drawing of the meeting of Sherman and Johnston in the Bennitt farmhouse from Harper's Weekly, 1865.

At their first meeting, Sherman handed Johnston the telegram he had received from Morehead CIty conveying the news of Lincoln's assassination. Sherman initially offered surrender terms consistent with the military surrender at Appomattox; Johnston desired broader terms of surrender that would encompass terms of governance. Sherman was agreeable to these terms, and when they met the following day, April 18, Sherman proposed "a basis of agreement" which Johnston accepted. The surrender provided for an armistice that could be cancelled at 48 hours notice which would disband the armies following the deposit of weapons in state arsenals, recognition of state government, establishment of federal courts, restoration of political and civil rights, and a general amnesty. The generals signed the agreement.

These terms were rejected by Union Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and the cabinet, feeling a great deal less leniency in the wake of Lincoln's assassination. Orders were issued to resume hostilities immediately. General Grant was dispatched to Raleigh to take charge and he arrived on April 24 without advance notice to Sherman, which evidently infuriated Sherman. Grant instructed Sherman to negotiate terms similar to those given Lee at Appomattox. Confederate President Jefferson Davis had agreed to the broader terms, but, upon hearing of the Union's rejection, ordered Johnston to disband the infantry and escape with mounted troops. Johnston disobeyed orders; the two generals met again on April 26, 1865, and signed the final papers of a purely military surrender, which disbanded Confederate forces in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida - a total of 89,270 soldiers.

Most people are probably familiar with stories of Union and Confederate troops amusing themselves at Durham Station during the surrender proceedings, and how the troops availed themselves of John Green's brightleaf tobacco at his factory next to the train station. Union troops were also encamped at West Point. It is unclear as to whether the fraternizing at Durham's Station was truly a mixture of troops; the Union troops were encamped in a line stretching from West Point to Chapel Hill, though Durham's Station. The Confederate troops has been encamped further west, near Hillsborough. Perhaps the Confederate troops came east during the surrender proceedings and later parole proceedings from their encampments to the west. However, it is generally accepted lore that the dissemination of the brightleaf tobacco by these troops played a part in the popularization of what soon became Blackwell's Bull Durham tobacco.

Following the war, James Bennitt found it necessary to enter a sharecropping arrangement with his in-laws, and he continued to farm until 1875, and died in 1878. Sources differ as to whether his remaining family moved to Durham after his death, but his wife died in 1884. The farm and family name were frequently mis-spelled "Bennett" - which became the de facto spelling of the farm.

The farm property remained in the Bennitt family, inhabited by a granddaughter in the 1880s, until they sold it to Brodie Duke in 1890. Duke, ever the ambitious dreamer, offered the farmhouse for sale at the 1893 Chicago Exposition as a historic relic. He built a shell around the original house in an attempt to protect it from deterioration.

Picture of Bennett Place, looking northwest, 1880s.

(Courtesy Durham County Library / North Carolina Collection)

Buyers must have been skeptical of buying the unseen farmhouse from afar, as he had no takers. Duke sold the property to Samuel Morgan, founder of the Durham Fertilizer Company sometime after 1908. Morgan tried to rally interest in making the farm a historic site, but could not generate enough interest to make it happen prior to his death. The house, no longer occupied, fell into further disrepair. Locals and visitors began to cart off pieces of the farmhouse as souvenirs.

Bennett Place, looking northwest from the Hillsboro Road, 1910.

(Courtesy Durham County Library / North Carolina Collection)

Bennett Place in serious disrepair, early 20th century.

(Courtesy Durham County Library / North Carolina Collection)

Confederate Veterans at Bennett Place, ~1920. You can see the farmhouse inside the shell structure in this north-facing picture.

(Courtesy Duke Rare Book and Manuscript Collection - Wyatt Dixon Collection)

Morgan died in April, 1920. The remaining structures burned on October 12, 1921 (thought to be ignited by sparks from a passing train,) leaving only the chimney of the farmhouse intact.

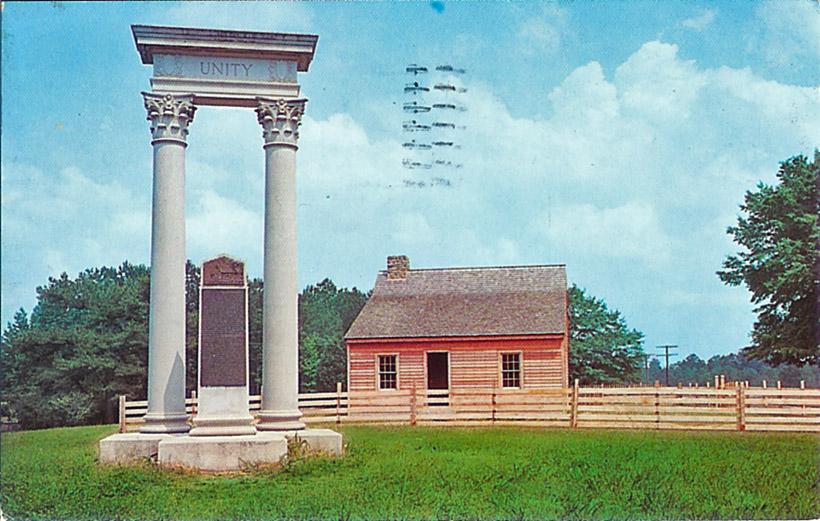

The idea to create a historic site stuck, and under the leadership of state legislators Reuben O. Everett and Frank Fuller, the state committed money to maintain the site and memorial should the Morgan family donate the site and the memorial to the state. All parties agreed. The State Legislature formed the Bennett Place Memorial Commission in 1923 with the intent of building a monument to national unity at the site. Sources differ as to who designed the monument - one, more credible source states that W.H. Dacy designed the memorial; another states that architects Milburn and Heister, who designed a multitude of other structures in Durham designed the monument. The monument consisted of two corinthian columns, representing the north and the south, with "Unity" in large letters on the architrave above the two columns. Over the objections of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, who felt the endeavor constituted a monument to defeat, the Unity Monument was erected on the site and dedicated in 1923.

Julian Carr and Bennehan Cameron officiated at the ceremony, and despite the protests of the United Daughters of the Confederacy to 'General' Carr, he struck a tone of unanimity, saying "There is no North; there is no South... one section responds as the other when the national safety is threatened."

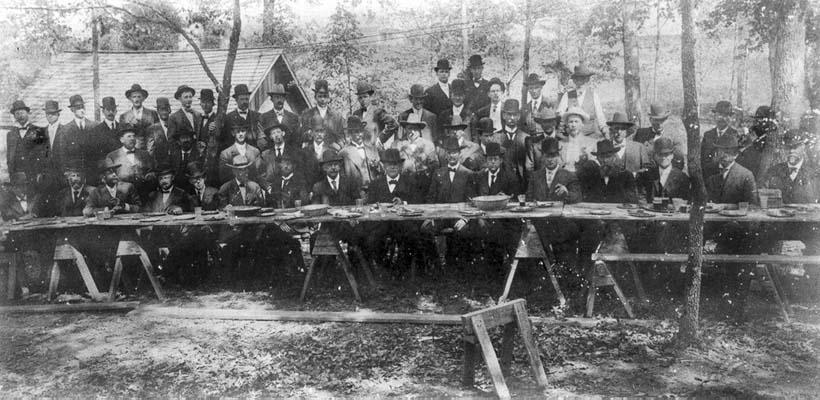

Carr, visible near the center of the crowd, speaking at the dedication of the Unity Monument at Bennett Place, 1923.

(Courtesy Duke Rare Book and Manuscript Collection - Wyatt Dixon Collection)

Dedication of the Unity Monument at Bennett Place, 1923.

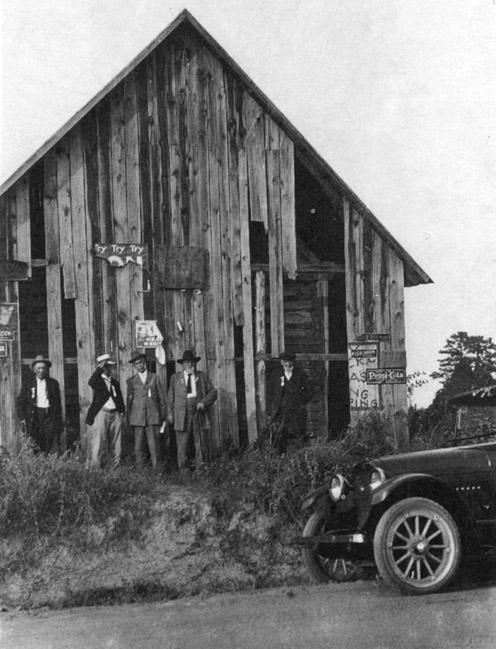

This picture is labelled as "Confederate veterans at Bennett Place, 1923" - but I'm not sure what the structure behind them would be, and I can't imagine a group of Confederate veterans at the dedication without Julian Carr in their midst.

(Courtesy Durham County Library / North Carolina Collection)

The dedication of the monument received almost no national attention. Carr would die one year later, in 1924. The Rotary Club bandstand was moved from the original Rotary Park in downtown Durham, where it had been placed in 1916, to Bennett Place that same year in order to make way for the Washington Duke Hotel. In 1925, the site was transferred to Durham County. The site became little-known and little-visited over the next 30 years.

Unity Monument and the remaining chimney from the Bennitt House, looking east in 1926.

I'm not sure if the Hillsboro Road was rerouted around the site in the 1920s or later; regardless, in the 1950s, Hillsborough road was re-routed to the north for the US70 bypass - the old Hillsboro Road became Neal Road.

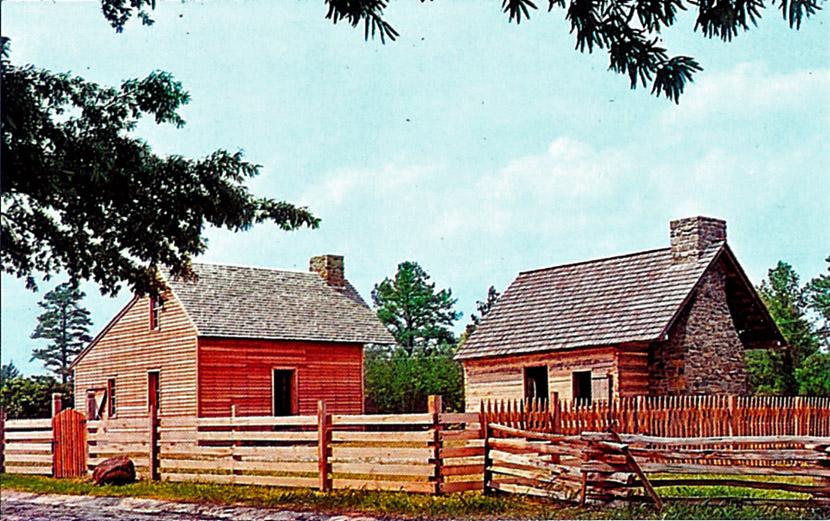

In 1958, a daughter of Frederick L. Bailey, former agent for Erwin Mills, donated money for the reconstruction of the Bennitt house. In 1960, Charles Pattishall, a Durham businessman with an interest in Civil War history who had been appointed to a committee headed by Dr. Lenox Baker to plan a Bennitt house reconstruction noted that the former William Haynes Proctor house at 1917 Chapel Hill Road, which was in the process of being torn down, consisted, under a Victorian exterior, of log structures of similar size and vintage as the Bennitt structures. Per Jean Anderson, the main structure was found to fit the old house foundation very closely. It appears that one wing of the house was separated and transformed into the kitchen structure. The reconstructed smokehouse may have come from this structure as well.

The reconstructed buildings, looking northwest, 1962.

(Courtesy Chris Graham)

The Unity monument and reconstructed buildings, looking east, 1962.

(Courtesy Chris Graham)

In the 1970s, Bennett Place became a State Historic Site. A modern visitor center was built on the site; it is free and open to the public. The site is periodically used to for various civil war re-enactments.

Looking northwest from the original Hillsboro Road, 02.12.09.

Kitchen (foreground) and smokehouse (background).

Smokehouse, 02.12.09.

The Rotary Club bandstand, formerly located downtown at Market and East Chapel Hill Sts., 02.12.09.

Reproduction of the Bennitt Farmhouse, formerly the Billy Proctor house (with the original Bennitt chimney,) 02.12.09

Unity Monument, placed at the site in 1923, 02.12.09.

Find this spot on a Google Map.

36.028924,-78.974592

Comments

Submitted by Suzy Barile (not verified) on Thu, 6/16/2011 - 2:00am

Must take issue with the comment: "Governor Zebulon B. Vance of North Carolina, seeking to avoid the destruction visited upon previous states Sherman had marched through, sent a peace delegation to Sherman offering to surrender the State upon his promise to help terminate hostilities and to recognize the State government. This proposal was evidently never addressed amidst the larger movement towards surrender and the end of the war." Vance sent former governors Swain and Graham and they negotiated the surrender of Raleigh and obtained Sherman's assurance of protection for both it and the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.