---

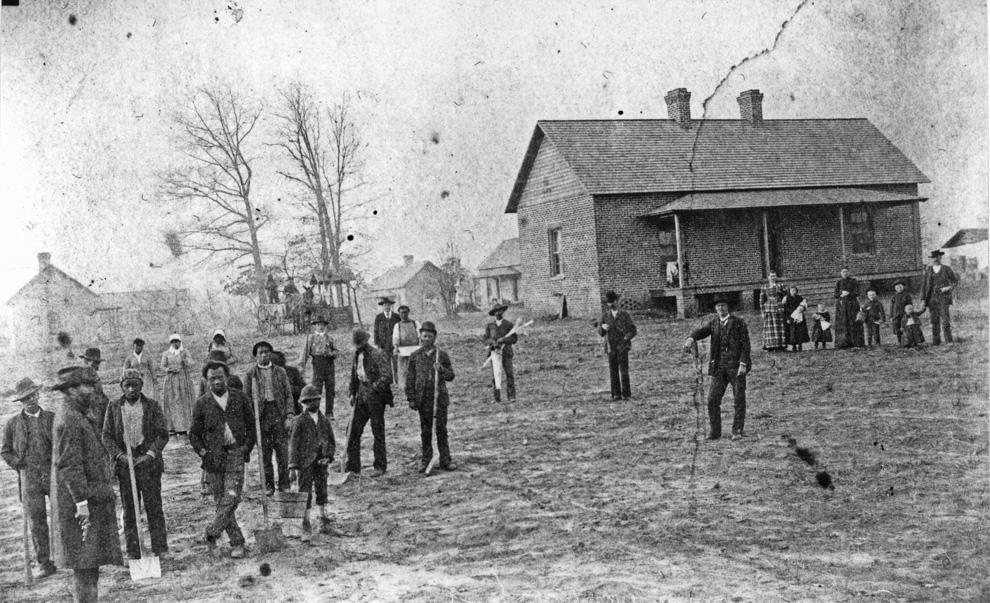

Prison Farm / County Home, 1880s.

(Courtesy Durham County Library / North Carolina Collection)

On November 15th, 1881, the County Commissioners purchased a tract of 138 acres of land on Roxboro Road, then about three miles north of Durham, from WA Wilkerson for $1393.75 and erected a frame house for "the care of the aged, indigent and infirm." Brodie Duke, who owned a furniture store at that time, sold the county furniture for the facility. They appointed John W. Evans as superintendent of the facility. In March 1882, the county commissioners also decided to build a prison/work house "for the confinement of criminals undergoing sentences of not over ten years" was constructed "separate and apart, however, from the cottages of the unfortunates of the first named class."

Prison labor, and labor provided by able-bodied, impoverished residents, was used to maintain the facility, including cleaning, cooking, and tending the farm on-site to provide food for the inmates and residents of the poorhouse. The prisoners also did off-site labor such as road work and "such other manual labor as comes least in conflict with free labor."

County Home, 1881.

(Courtesy Duke Rare Book and Manuscript Collection - Wyatt Dixon Collection)

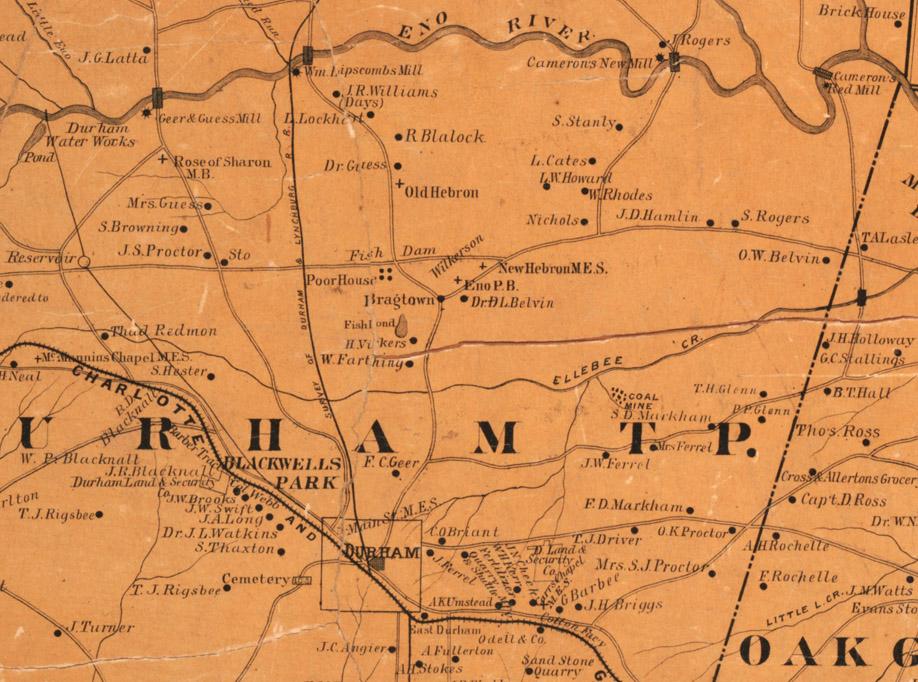

1887 Map of Durham showing the location of the 'Poor House'.

Mangum's 1887 Directory of Durham gives a description of the facility:

"Within the last few years the lands have been brought into a high state of cultivation, whilst neat and well ventilated cottages (some of brick), have taken the place of the poor cabins that formerly served as shelter for the unfortunates whose only crime was being poor and mentally or physically infirm. The poor inmates are now well-housed, clothed and fed, and are surrounded by Christian influences and accorded humane consideration in striking contrast with the neglect, squalor and savagery that prevails at some similar institutions in some counties of the State. Here God's poor unfortunates find a home indeed, instead of a 'poor house' and an inferno. Here they are not surrounded by humiliating reminders of their helpless dependency. A neat Chapel has recently been erected, where lay services are held every Sunday afternoon. To the untiring efforts of the present Superintendent, aided by his subordinates, and supplemented by the Board of Commissioners and County Physician, much praise is due for the truly satisfactory condition of this institution."

By state law, each county appointed a warden of the poor (later re-branded superintendent of public welfare) who maintained a roll of those considered the 'outside poor' - what we would refer to as homeless - these rolls were not regularly monitored, and forms of assistance could range from financial to work to housing at the county home. Despite the impetus to establish some form of facility to provide some accommodation for people who were certainly considered society's 'undesirables,' (n.b., three miles out of town) conditions in the county home were less than optimal, as you might imagine. The below is from a Master's thesis on Durham County's impoverished, by Rebecca Thaler:

In 1890, the county commissioners requested that a grand jury investigate John W. Evans, the superintendent of the poorhouse and workhouse since their creation almost a decade earlier. In the ensuing case, the county charged Evans with mistreatment of paupers and prisoners, misappropriation of county funds, and general mismanagement. One witness, J.L. Massey, who had served as prison guard for fourteen months, testified that Evans designated certain prisoners as “trustees” and let those men have the run of the grounds. Evans allowed one trustee, a Mr. Hicks, to leave the grounds altogether, “being at liberty to spend his nights and Sundays at his home” five miles away. Massey also testified that Evans “lets them [the trustees] eat at his own table” along with the superintendent’s family. The county commissioners appear to have been justified in their concern that Evans allowed at least some prisoners to have the run of the poorhouse grounds. The Grand Jury also investigated two cases in which Evans was accused of cruelty and neglect of a poorhouse inmate. When William Cameron, a black pauper, had been admitted to the county home the summer before, he had been suffering from gangrene in his foot. A local doctor who attended to poorhouse inmates amputated Cameron’s foot; then, a few days later, the doctor found that “the disease had advanced up his leg” and performed a second operation to amputate more of the man’s leg. Cameron’s leg, exposed in the summer heat, “became infected with maggots,” and he died shortly thereafter. Several paupers testified that Evans had been left unattended. Another black man living in the poorhouse, Jesse Mosely, had an “unexpected hemorrhage of the lungs” and died unattended, “suffocating in a pool of his own

blood.”

Although the Grand Jury concluded that “the management of the Poor House is by no means what it should be, being in many respects worse than can be imagined,” the testimonies of guards, doctors, and paupers offered a mixed assessment. The county commissioners ultimately ruled that Evans had not committed “any criminal act or neglect” and retained him as superintendent until Evans quit.

By the 1890s, the county home had been enlarged to 9 frame buildings; on a state level, housing of criminals with the impoverished had come under some fire. In one particularly colorful quote, which gives you a sense that not a few of the convicted were prostitutes, Rev. G. William Welker chairman of the State Board of Charities opined that “the respectable, aged, and infirm pauper is shut up with the wornout strumpet, whose very presence is pollution.” Particularly of concern was the rise in children living at the county home - both those that had come with their families, as well as those born at the home. Much of the rise of private charities in the 1890s and early 1900s arose from the failure of the county home to provide adequate care and housing - in particular to those considered 'worthy'. White children epitomized that 'worthiness'.

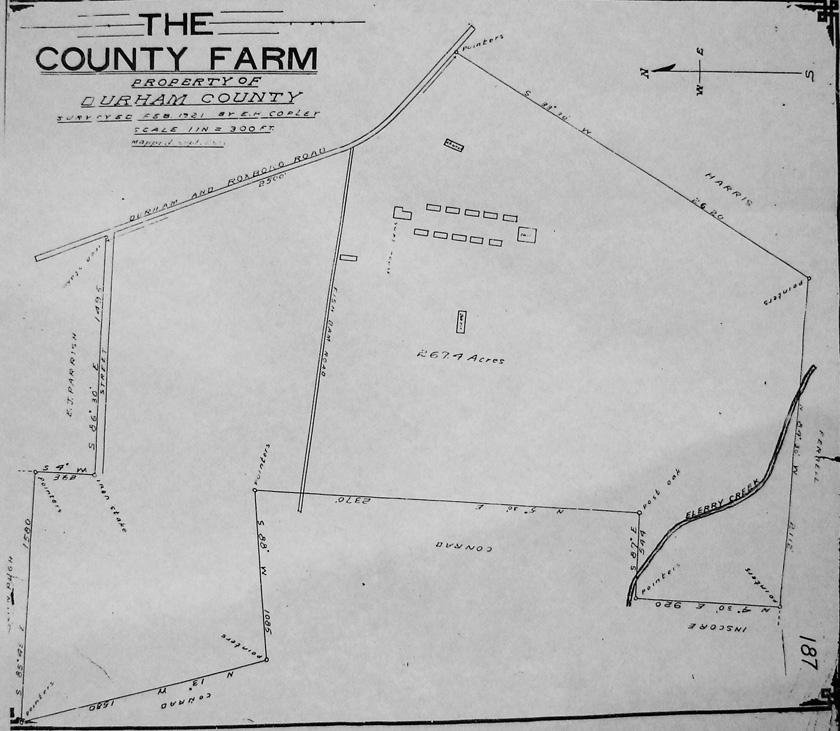

1921 Survey Map, retrieved from the Durham County Register of Deeds.

(Provided courtesy of David Southern and Steve Rankin)

By 1925, a new Durham County jail had been built approximately 3/4 mi. west of the county home on Broad Street. At least some of the prisoners formerly housed at the county home were moved to that facility, alleviating some of the discomfort arising from the co-housing of the impoverished with misdemeanants. A new County Home main building was built that same year at a cost of $175,000, and the facility became primarily used to house the impoverished and disabled.

This use began to wane during the 1930s; Anderson notes that, by 1937, county homes / 'poor houses' were being downsized, their functions supplanted by the rise of Federal and state programs to provide social security and welfare benefits. Durham's persisted, however, providing primarily housing to disabled people.

County Home from N. Roxboro Road, 11.06.58.

(Courtesy The Herald-Sun Newspaper)

In 1960, Durham County Memorial Stadium was built on a a portion of the county home land, closer to North Duke Street. It primarily provided a football facility for local high school teams.

Aerial of the county home site, around 1960, looking north. N. Roxboro Road runs into the background on the right, North Duke St. on the left. The then-new county stadium is visible, and the county home and farm outbuildings are to the right.

(Courtesy The Herald-Sun Newspaper)

View of the County Home and outbuildings looking east towards Roxboro, 1960

By 1967, the facility was managed by Andrew S. Holt, a former director of the YMCA. Wyatt Dixon wrote about the facility in 1967 - you'll have to read between the treacly lines of text to get some sense of the place.

"The inmates of today live in comfort and are well-cared for. Good wholesome food is served to them in a large dining room, and their leisure time activities include entertainment several nights each week in the auditorium. Prisoners are permitted to attend these functions also.

The County Home is divided into four departments and the residents are admitted by the welfare department whose caseworkers determine whether they are entitled to be admitted. They also determine the amount of money each shall pay. Holt says there usually a waiting list of person desirous of entering the home.

The residents are all ambulatory, but when they need infirmary treatment they are admitted where a staff of nine nurses provide care for the sick. Dr. AH Powell is the home physician and prisoners also are assigned to care for the patients. Usually two beds in the infirmary are kept unoccupied for use of emergency cases.

A total of 122 people at this writing are Holt's charges. Seventy-four of them are residents of the home, the remaining 48 being prisoners. Forty of the residents are women. All but eight of the prisoners are males.

Mrs. Holt also plays an active and important role in the home's operations. Pretty artificial flower arrangements made by her add to the attractiveness of the building, and many favorable comments have been paid them by people who have visited the institution. She also directs the work of growing flowers which are used in making the home more attractive."

County Home, looking northwest from near N. Roxboro Road, 1969.

(Courtesy The Herald-Sun Newspaper)

Durham's County Home continued operating until 1969. At closing, disabled and elderly residents were placed in rest homes and nursing facilities - there is no notation in the sources I consulted of what became of the prisoners.

Jean Anderson notes that, by the 1960s, both Lincoln and Watts Hospitals were providing outmoded hospital facilities to Durham. An initial plan to build a new, integrated Watts Hospital was soundly defeated by both Durham whites and African-Americans - by whites due to integration, and by African-Americans due to the loss of Lincoln Hospital.

A multi-racial Hospital Study Committee was set up, which recommended the construction of a new hospital, and the conversion of Lincoln and Watts into extended-care facilities. This initially also met with opposition, but eventually all parties agreed to the need for a new facility, and the measure passed. The site of the County Home was chosen, as it sat at approximately the geographic center of Durham County.

Construction of the new, then-487-bed hospital began in 1973.

Under construction, 06.08.73

(Courtesy The Herald-Sun Newspaper)

The hospital opened for business on October 3, 1976. In what is described as "an enormous undertaking" all patients were transferred from Lincoln and Watts hospitals on opening day. Those two institutions were closed as hospital facilities - Lincoln to become a community health center, and Watts to become the North Carolina School of Science and Math.

Open for business, 12.22.76.

(Courtesy The Herald-Sun Newspaper)

This facility was renamed Durham Regional Hospital in the 1990s, and, operated in partnership with Duke, continues to be the primary tertiary care center for the area.

Durham Regional Hospital / former site of the Durham County Home, 01.24.09.

The shift of the primary medical center to this location mirrored the suburbanization of health care that occurred throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Major metropolitan areas continue have downtown, urban locations, but less populous cities - and particularly those where the hospital was not tied to a university campus - saw their hospitals disappear out to the fringes of town.

As a result, the medical practices and other spillover economic benefits of the hospital went along for the ride. The medical practices that used to line Broad Street between Markham and West Club moved northward, as did practices from Fayetteville Street (although their buildings were being torn down.) New suburban-style medical 'office parks' were constructed to house these practices.

A high-ranking official at UNC Hospitals, where I did my training, once described UNC's land use aspirations as "follow[ing] the Wal-Mart model": High-volumes of cars carried by high-volume roadways to high-volume parking. UNC is certainly not unique in that regard, as it describes most major medical centers in the region.

I used to practice in one of these medical-office parks out by Durham Regional; it was fine for what it was, but an awfully depressing landscape - although not quite as surreal as the pseudo-traditional buildings housing medical practices in the Independence Park area behind Lowe's.

This environment helped shape my decision to leave medicine and become, broadly, an urbanist. How could I/we, as medical professionals, support an environment that was so damned hostile to pedestrians? I will never forget the images I have of disabled patients driving their Rascals (a type of scooter) down North Duke Street, because there were no sidewalks. As the kids say, OMG.

There is enough evidence out there at this point supporting highly connected, reasonably dense, pedestrian supportive environments that the medical community should be shouting for land use improvements, sidewalks, bike paths, street trees, etc. from their squat, single-story rooftops. And believe me, I understand that there is enough to do just chasing an ever-expanding list of ailments in a structurally-unsound/fundamentally-flawed healthcare system. And we are talking about crossing over the walls around not two, but three disciplines: between private healthcare and public health, and between public health and urban planning.

But just because medical practice folks may leave traditional environmental health (drinking water and the like) to the county public health authorities doesn't mean they can't leap over those walls to urban design and land use - because unlike water treatment, each and every medical professional makes at least one transportation decision every day, and land use decisions at least every time they buy a house, rent office space, or go to work with a practice that rents office space.

At the end of the 19th century, these were not separate disciplines - physicians forcefully advocated for environmental changes in their communities - Dr. John M. Manning was one such physician in Durham. But the professionalization of urban planning and public health relegated physicians to a primary role of writing prescriptions and cutting things out of people - although there have always been activists and advocates among our ranks. In urban planning, economics became the disciplinary firmament upon which planning decisions would rest, and public health would fail to evolve within urban planning for 90 years - resting upon notions of urban spaces breathing miasmas that could be dispersed with enough distance between uses that were not 'complimentary'. What allows you the greatest distance between uses? Cars and trucks, which demand ever-bigger roads and parking space that could support a small house.

And while planners have begun to compensate for the flaws in use-based zoning, the stated justifications are unconfident and uncertain, often crippled by resting on the notion of design superiority - which is too subjective to ever persuade anyone, and may have been permanently sullied by Le Corbusier and other silly adherents to the notion that modern architecture would save the world.

The time, therefore, is ripe for a return of medical professionals to the fray. We have begun to see the effects of what we have wrought - a car-only world that disenfranchises the elderly, children, the disabled, and, more broadly - the non-iron-clad human from participation in our public space, trapping them in segregated private spaces from which they can only escape in a 2 ton vehicle. Notwithstanding broader impacts on the environment, this sedentary isolation does not make for healthy people.

In not-so-short, I would ask medical professionals, the next time they are at work, to think about how many places they could reasonably walk to during their lunch hour 'break'. I remember being moved by the number of patients who told me that they would get out and walk during their lunch hour, but they found walking in circles around the company parking lot too depressing. Advocating for better land use and transportation is, in short, patient advocacy.

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.