---

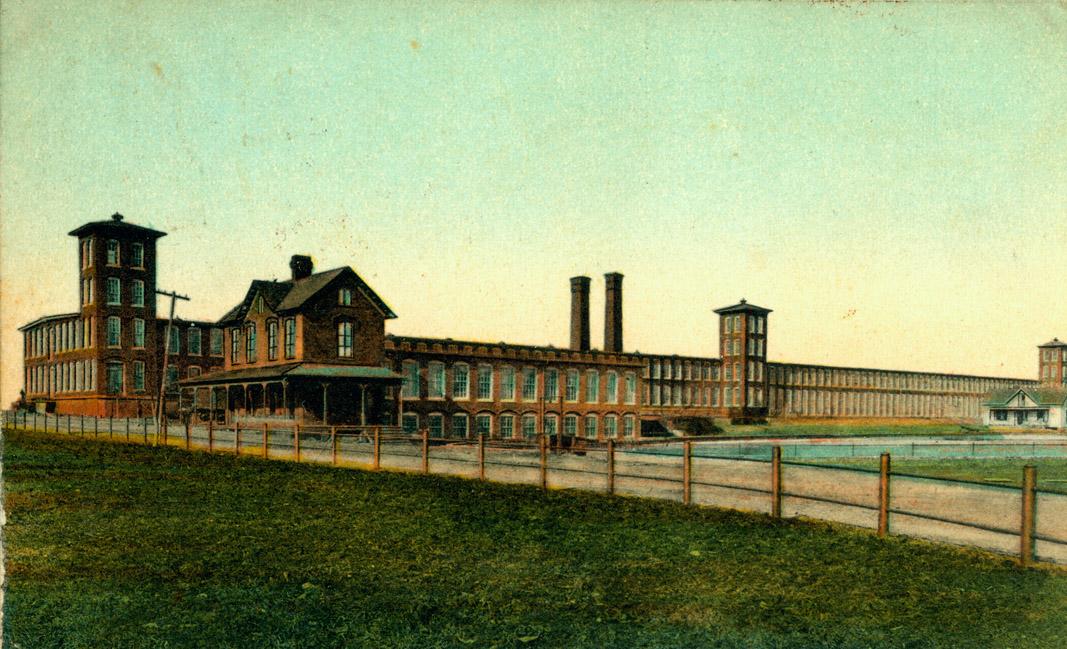

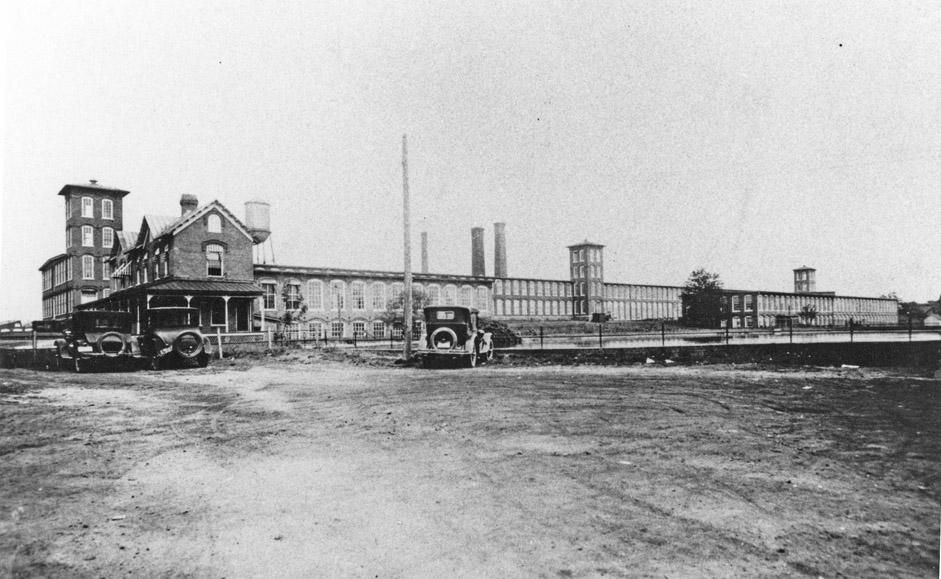

Erwin Mill No. 1 and office building, early 20th century

(Courtesy John Schelp)

Julian Carr's success with Durham's first textile manufacturing plant, the Durham Cotton Manufacturing Company, which returned 20-30% net profit in its first 6 years, showed the viability of the industry in Durham and, more broadly, the south.

The Dukes, who had followed Carr's lead 10 years earlier - establishing W Duke and Sons tobacco Co. in the wake of Carr's success with Blackwell's Bull Durham - sought to repeat the model in the textile field. Carr had proved the market; the Dukes would seek to build it better and more profitably.

George Watts and Ben Duke recruited William A. Erwin from Burke County, where he had grown up on the family plantation of Bellevue near Morganton as part of the Holt textile family, purportedly on the recommendation of Southgate Jones. Erwin was 36 years old when he came to Durham, but not inexperienced; for the previous ten years, he had been treasurer and general manager of the EM Holt Plaid Mills in Burlington. Erwin confidently told Ben Duke that he could derive 40% net profit from the business they were to establish. Erwin invested $40,000 in the venture, while Ben Duke and George Watts invested $85,000.

The group sought additional investment from northeastern textile manufacturers, who were disinterested. Duke and Watts provided an additional $75,000 in capital to start the venture. Duke was emotionally invested in the success of the project as well - terming it one of [the Dukes'] "pet enterprises."

Repeated in every single source referenced by me is the same anecdote regarding the naming of the mill after Erwin. I'll repeat it despite the fact that it sounds made-up-after-the-fact to me. After some discussion of what to name the new venture, BN Duke remarked "Let us name it for this young man; then if it fails the onus will be upon him; and if it succeeds, it will be to his glory." So it was that the venture became the Erwin Cotton Mill.

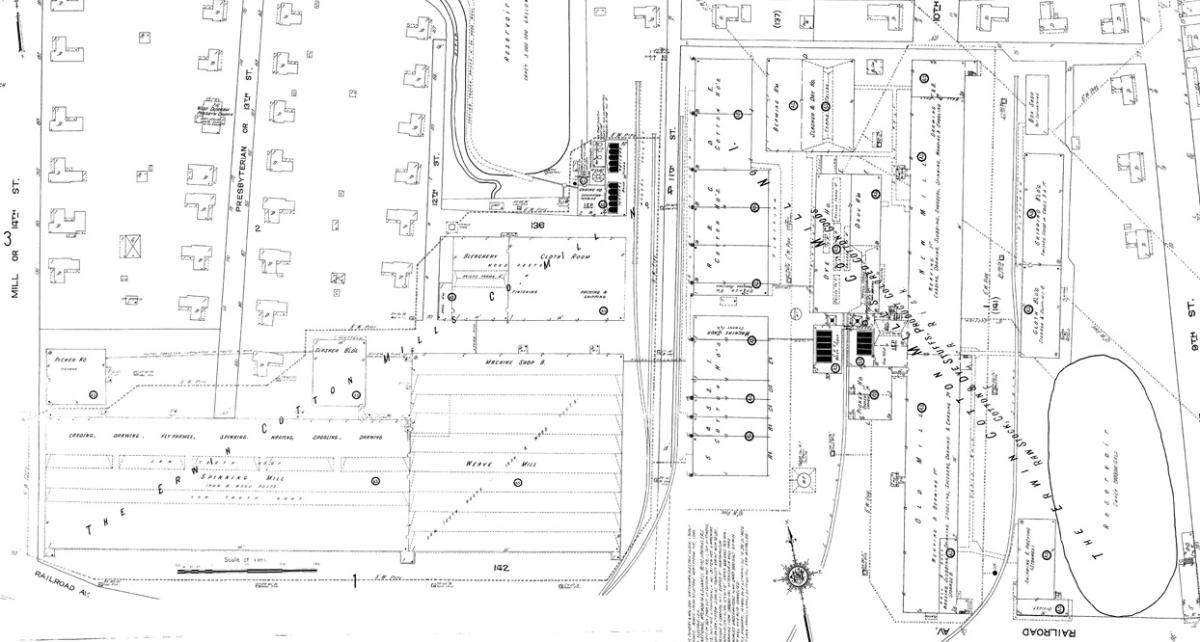

Construction began in the Fall of 1892; the company bought several adjacent tracts of land in West Durham and built a 75 x 347 foot, two-story factory, a picker building, dyehouse, boiler room, engine house, and office building. The company began the construction of residences to the west, north, and east of the textile factory.

The factory began by producing muslin, used for tobacco bags, but, at Erwin's directive, began to produce denim, which, up to that time, had not been produced in southern textile factories. The mill's production grew rapidly, almost tripling the following year, thereby becoming the textile mill with the highest production in Durham. By 1895, the factory had 375 workers working on 11,000 spindles and 360 looms to produce fine muslin, chambrays, camlets, and denims. By the next year, the company had 1000 workers, 25,000 spindles, and 1000 looms. Erwin Mill became one of the largest denim producers in the country.

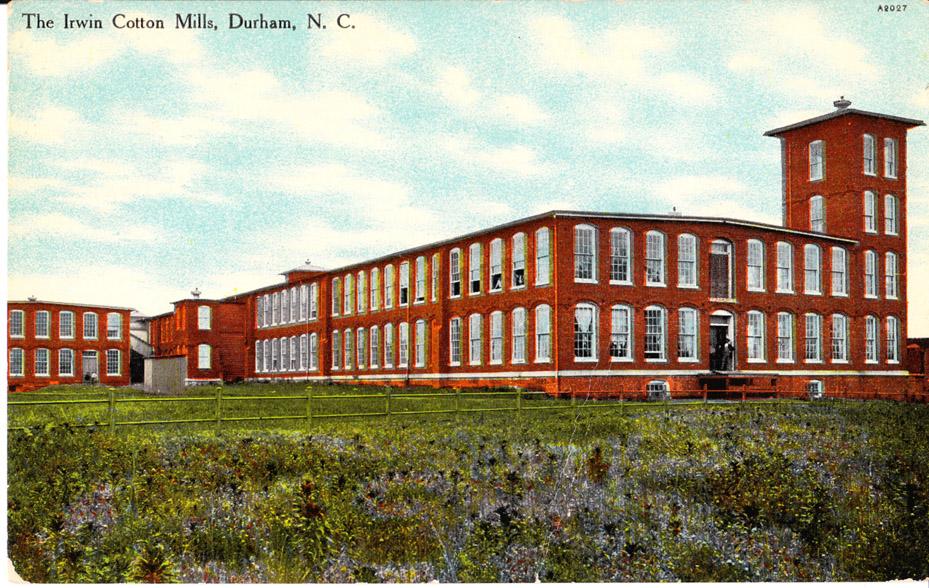

The "Irwin Cotton Mills" - looking north

(Courtesy Dave Piatt)

Erwin was secretary-treasurer of the company, the title bestowed upon the chief operating officer. He recruited Edward K. Powe, an executive at the Altamahaw Cotton Mill in Alamance County, to be plant manager. Erwin set out to build a self-contained community as well as a factory; a company store was established at West Main and Ninth Street [which contained a post office], a meeting hall was built, and, by 1900, 440 houses had been built in the area around the mill.

One the primary 'advantages' that a southern textile mill had over the well-established northern mills was southern poverty, and the resultant ability to pay workers low wages. Per Robert Durden, in 1890, a "skilled man" received average daily wages of $1.00 to $2.50, a "skilled woman" 40 cents to $1.00, and children from 20 to 50 cents. Yes, child labor was alive and well during this era, and a high percentage of factory workers were women and children. In the progressive cost calculus of Richard Wright, coal cost $3.15 to $3.25 a ton, and "girls could be had from $2.50 to $4.00 a week." Erwin mills would, during the 1890s, run 66 hours a week and employ children older than 12. By the early 20th century, the large northeastern textile manufacturers had started moving their operations southward to utilize these 'advantages.'

Success of the venture necessitated expansion in relatively short order; in 1898, the original mill building was expanded to twice its original size by lengthening the building to the north. The original two end towers became the south and middle towers, and a third tower was added to the north end. An addition was added to the rear (north side) of the office building, and its cupola was removed.

In 1899, the Pearl Mill, a Brodie Duke venture came under the management of Erwin as well (it had been reorganized by the other Duke brothers and Watts in 1895 following one of Brodie's financial reversals.)

The success of the Erwin Cotton Mill sparked a period of expansion. Mill No. 2 was constructed on the Cape Fear River, beginning in 1902 - the associated mill town would be called Duke, but later renamed Erwin so as not to evoke confusion with Duke University. Mill No. 3 was constructed in Cooleemee during 1901-1906.

The Erwin Cotton Mills company was financially successful venture; in 1904 the board of directors declared a stock dividend of 200%, and the Erwin announced a net profit of $215,000 - a $30,000 increase from the prior year.

In the early decades of the 20th century, workers began to prove harder to attract than during the repeated economic depressions of the 1890s; Erwin decreased work hours to 62 hrs 40min a week in Durham to help retain and attract labor. Contraction of the textile market after the Spanish-American war did not help matters. Sales continued to decline significantly during the latter 00s; Erwin and Ben Duke organized agents to sell Erwin textiles in Asia in hopes of opening new markets. Duke and Erwin pushed hard for increasing protective tariffs on imported textiles, which did not succeed. In 1913, the Congress reduced tariffs on imported goods from previously high levels. However, the macroeconomic climate appeared to be improving to a point that the company could succeed in a reduced-tariff market, and profits once again grew during the 1910s.

By 1907, a cotton storage house and several brick structures for "beaming and slashing" had been added to mill no. 1.

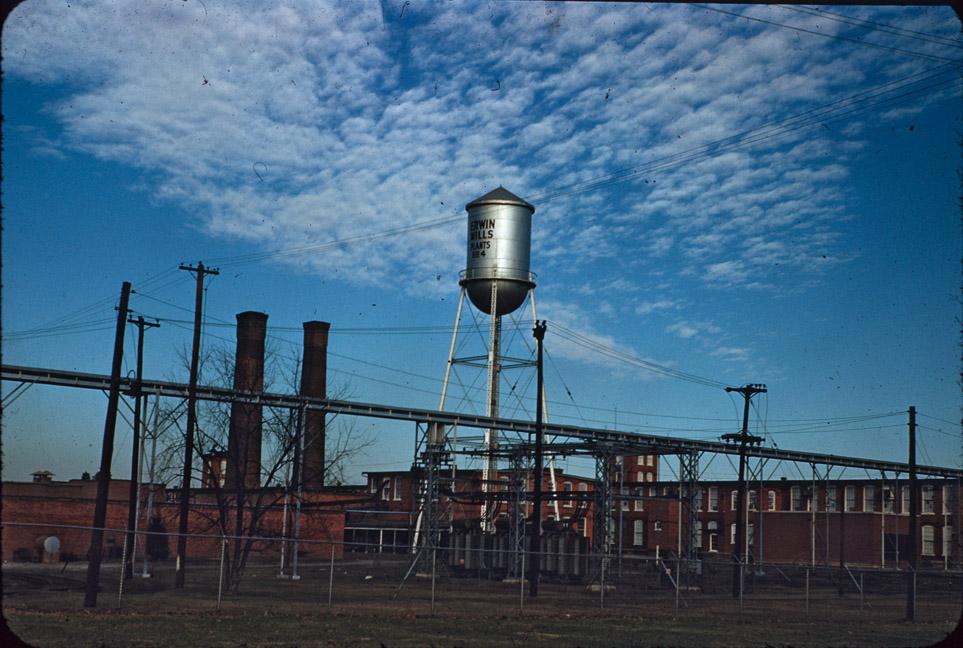

When Erwin announced that the company would expand to a fourth mill, he would not state where the mill would be located - he teased the city of Durham with the notion that the mill would be constructed in Durham, but refused to commit to doing so. Durham had designs on the incorporation of West Durham into the municipal fold, but Erwin wanted none of it; West Durham was a mill town, and his mill town at that. When Erwin said that the mill would be located in the city that "offered the best advantages" Durham backed away from annexation. Mill No. 4 was built along Mulberry St. immediately to the west of mill No. 1 in 1909.

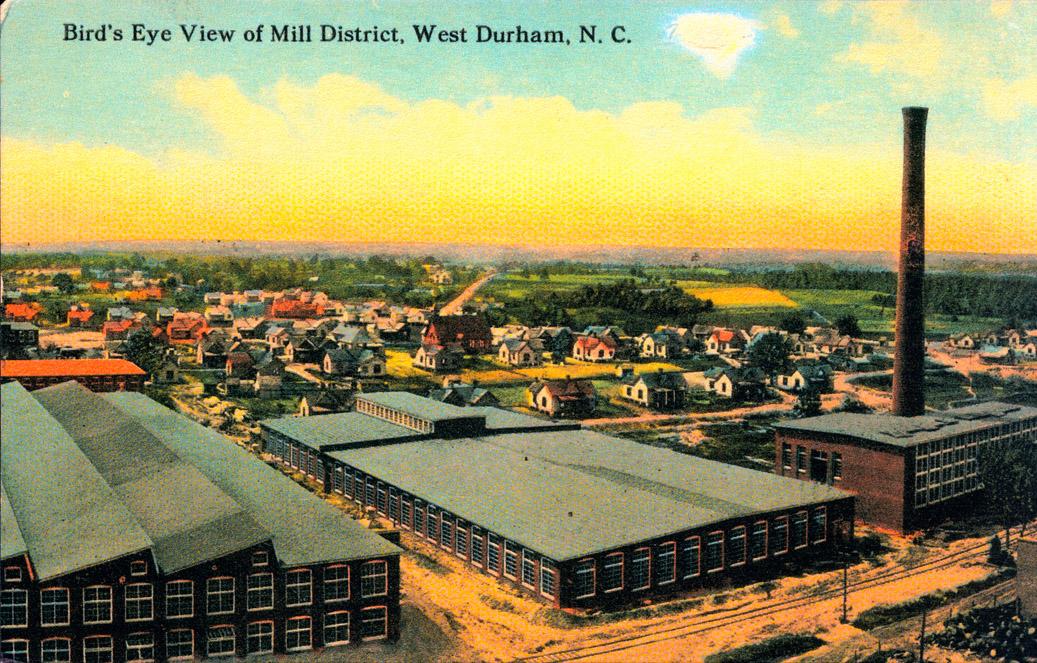

Erwin Mill No. 4, looking northwest from Mulberry St., 1910s.

(Courtesy Duke RBMC - Digitized by Digital Durham)

Full panoramic shot of Mills No.1 and No.4, looking north from Mulberry St., 1910s

(Courtesy Duke RBMC - Digitized by Digital Durham)

Part of Mill No. 4, and the mill village stretching westward, 1910s.

(Courtesy John Schelp)

It didn't take terribly long after the establishment of Durham's tobacco and textile factories for initial talk of unionization to take hold—the Noble Order of the Knights of Labor, founded in Philadelphia in 1869, had five assemblies in Durham by 1888. In 1900, a union organizer reportedly managed to sign up 191 workers at the Erwin Mill; the reasoning was to try to establish a mutual aid fund (the precursor to health insurance, which typically also provided death benefits) that Erwin had been unwilling to provide or meet with them about. Once the unionized people were on their knees from lost wages, Erwin made a show of 'taking them back' and alleviating their distress. People would be helped / charity would be given, but on Erwin's terms.

Labor conditions would begin to change slightly by 1913, when night work was restricted to 7-9pm and 1916, when the minimum age for employment was raised to 14.

Erwin Mill, 1913.

Erwin, not infrequently referred to as 'Pa' Erwin, truly acted the part of the father figure in West Durham, and the flip side to his paternalistic control of the lives of mill workers was a genuine concern for the well-being of his community. He offered 11 weeks of free night school to workers, and financially supported clubs, libraries, and nurseries for the workers. He repeatedly referred to the employees of the mill as "my people" and, per multiple anecdotes, seemingly knew every worker by name. He freely supported churches and community organizations. Failure to live by his standards, though, could exact harsh penalties. Erwin would ride his bicycle around the neighborhood to ensure that residents adhered to a 10pm 'lights-out' rule. Arrests for public intoxication were grounds for dimissal from the mill, and loss of housing. Various other moral transgressions could result in similar penalties. Many of those shunned often went to live in 'Monkey Bottom' - the low ground to the southwest of Erwin Road and West Pettigrew between Swift and Oregon Sts. (now Erwin Field.)

Mill No. 1, 1920s

(Courtesy Durham County Library)

The construction of Erwin Auditorium in 1922 provided recreation facilities for the community, as did the adjacent Erwin Park and Erwin Field one block away. A zoo, playground, and tennis courts accompanied Erwin Auditorium; community events in and around the auditorium were frequent.

Control of the company over the mill village began to slip by the mid 1920s. Erwin's opposition to the annexation of West Durham could not hold, and the city incorporated the village into the city in 1925. Increases in factory mechanization led to a faster and faster pace of work for employees, who struggled to keep up with the pace of the machines. Dissatisfaction with working conditions created fertile territory for union activity to gain greater traction at Erwin Mill. National legislation during the New Deal would lead to protection of workers' right to organize, established a 25 cent/hr minimum wage, 40 hour work week, and control of child labor.

Erwin Mill No. 1, office building, and cloth and shipping buildings, looking west-northwest from near 9th Street, 1920s.

(Courtesy Durham County Library)

By the early 1930s, Erwin had become ill with cancer; he died in 1932. He was succeeded by KP Lewis. To Lewis, Erwin had written in 1926:

"I urge upon you to keep in mind that we cannot let go the cordial enterprising spirit which it has cost us much to establish in our villages and in the hearts and minds of those serving our Company in a responsible way, for the spirit and soul of our business is the life of our business and has roots deeper in same than what we call 'policy'. We must treat everybody right, but must keep in mind that our stockholders come first."

Hanging onto the old 'cordial enterprising spirit' would be a challenge for Lewis, as putting the stockholders' demands for greater output first had caused dissension in the ranks, as demonstrated by increasing unionization. Tobacco workers in the city had begun to organize during the 1930s as well, as had building trades in Durham. In March 1934, a union meeting was held at "West Durham High School" - KP Lewis utilized spies to gain information about the organization attempts of his employees. Dropping wages (a 63.5 drop between 1920 and 1934) had helped foment workers' complaints. Management felt that the dissatisfaction was being sown by so-called 'flying squadrons' - union leaders from elsewhere who would come to communities and "try to disrupt [their] operations."

Increasing unionization of employees and dissatisfaction with working conditions and wages led to a general strike of thousands of textile employees throughout the southeast begining on labor day - September 3, 1934. Per the N&O several hundred striking Erwin Mills workers met to form their protest at the Carolina Theater and marched down West Main St. to Erwin mill, where they confronted president KP Lewis over better working conditions. In total, 5200 workers in Durham from Golden Belt, Durham Hosiery Mill No. 1, the Durham Cotton Manufacturing Company, and Erwin Mills participated in the strike.

At the end of the strike, though, little had changed, and union membership decreased in Durham.

By 1937, the Textile Workers Organizing Committee had unionized all five Erwin mills. Erwin Mills, and Lewis, seemed to accept the unionization of their workers with less bitterness than most industrial employers, although Lewis continued to chafe at negotiations with union representatives rather than directly with employees. Difficult working conditions changed little leading to repeated strikes over the subsequent decades.

Opinions of the working conditions at Erwin mill obviously varied widely, given all of the factors that influence people's opinion of their jobs both then and today. While some oral histories bemoan the very difficult working conditions, other histories speak to how wonderful a job at Erwin mill was compared to what else was (or wasn't) available. I quote from an oral history of James Jackson, resident of 715 15th St., from September 1938:

"I don't know of a better company to work for," he declared. "The officials here have the worker's interests at heart. They've furnished us with a fine Auditorium where a person can find free amusement if he wants to. They order coal in big lots and sell it to us without profit for $6.50 a ton. They keep the houses in good repair and rent them to us for almost nothing. I pay $1.50 a week for my four rooms, bath room, and garage. If I didn't live in a company house I'd have to pay $5 a week for a house not kept in as good condition to this.

"There are very few people working in the mill who make less than $12 a week when they work full time. Some of the help's sent out now and then as much as a day out of a week to rest but never more than that. We make standard goods -- sheets and pillow cases, you know -- and we generally have orders on hand all the time.

"I feel like people living here at this mill have as good or better chance for a decent living as most people working in stores, in offices, and such places where they don't make any more than we do and have a sight more house rent to pay.

"Of course the company don't have enough houses for all its help. There's some working in the mills here that's paying $20 a month for rent because they caint get a company house. But the majority of us has the advantage over other working people when it comes to rent."

The company continued to expand during the mid-20th century. The Pearl Mill officially became Erwin Mill No. 6 in 1932. In 1948, the Diana Mills in Wake Co. became mill No. 7 and the Stonewall Mills in Stonewall, MS became Mill No. 8.

Erwin Mills, looking southwest, 1930s

Erwin Mill was the recipient of government contracts during World War II; as with most industry, strike activity was put aside in the name of the war effort. Erwin Mill added a third shift to meet increased production demands. During the war period, the mill began to sell off its mill housing - beginning in 1942. Most of the housing north of the railroad tracks was sold off to employees in subsequent years.

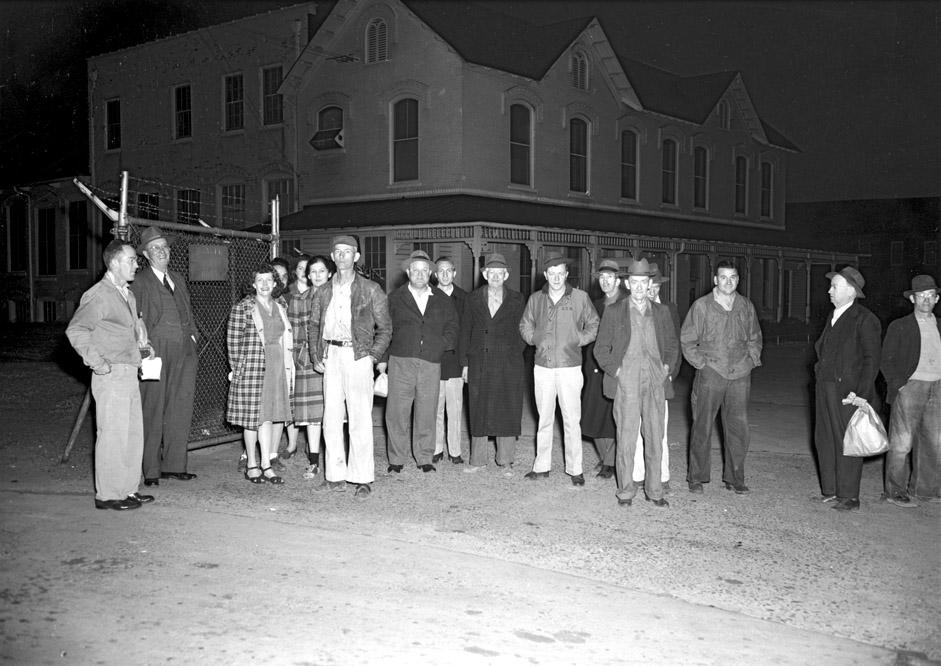

Second or Third shift workers outside of the Erwin Mills office building at night, 1940s

(Courtesy the Herald-Sun)

Interior view of one of the two mills in Durham, 1940s

(Courtesy the Herald-Sun)

Immediately after the war, labor unrest began anew.

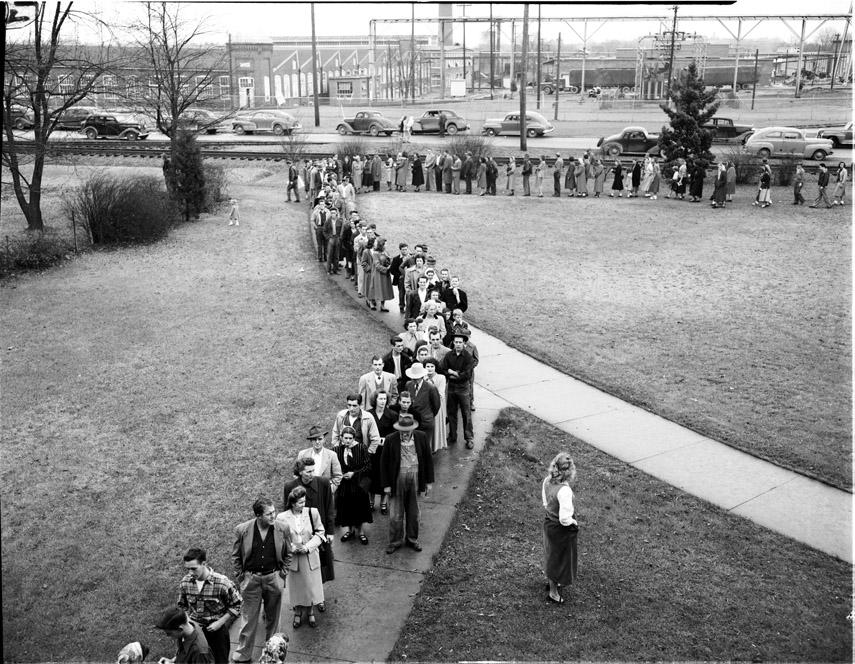

Erwin Mills strike, 1945 - looking northwest from the south side of the railroad tracks, in front of the Erwin Auditorium, towards Mill No. 4

(Courtesy the Herald-Sun)

One sign reads:

" $5

40 Hours

$2200 ?

It won't support a

Familey"

Another reads:

"1892-1945 = 53 years ........ as poor as ever."

Erwin Mill Strike, 1945, looking north at Mill No. 1

(Courtesy the Herald-Sun)

Things were somewhat different this time. In 1948, KP Lewis would resign as president of the company and became chairman of the board of directors. New President William Ruffin succeeded KP Lewis, and seemed to change the tenor of relations between the company and it workers. Ruffin had hired Duke University economist Frank T. DeVyver in 1943 (while a member of the board) to study production at the plant. DeVyver enjoyed a good relationship with the union, set up an employment office, grievance procedures, and other methods for employees to direct feedback to the company. The 1945 strike ended with management agreeing to all requests, including 65 cents/hr pay, a 45 minute lunch, and one week of vacation for employees with less than 5 years experience, 2 weeks for those with greater.

By 1951, the company owned 8 spinning and weaving mills as well as two finishing plants with over 220,000 spindles and 6000 looms which consumed 140,000 bales of cotton a year and produced 165,000,000 yards of cloth. The company employed 6400 people. The major products of the Durham mills were sheets and pillow cases, made in "three popular muslin grades." Other mills produced a variety of other types of cloth.

Another strike that same year, called for by the national union, was considerably less amicable, as workers attempted to blow up parts of the mills.

Erwin Mill Strike, 1951; looking south from Mulberry St. towards Erwin Auditorium

(Courtesy the Herald-Sun)

Striking workers marching west on Mulberry St., 1951 with the Erwin Mills office building and the West Durham Post Office in the background.

(Courtesy the Herald-Sun)

Perhaps that was the breaking point for several of the stockholders of Erwin Mills, as by 1953, they sold a controlling interest in the company to Abney Mills of South Carolina, which would use the plants for production of sheeting. The true impetus was more likely, per William Ruffin, an inheritance tax problem. John Sprunt Hill, who, as the son-in-law of George Watts owned 20% of Erwin common stock, fought ceding control of the mills to a South Carolina Company vigorously. When he lost a bid for Mary Duke Biddle's stock to Abney Mills, he tied the transfer up in court for a "protracted period." Hill was evidently opposed to changes at the mill instituted by Ruffin, although it isn't clear what he specifically objected to. Hill lost the battle.

Erwin Mills, 1950s

(Courtesy Durham County Library)

Erwin Mills and surrounding mill village, bird's eye view looking east from ~ above 15th street.

(Courtesy the Herald-Sun)

Between Mills No. 1 and No. 4, near Mulberry, looking northeast towards the back of Mill No. 1, 1951.

(Courtesy Duke University - Lewis J. McNurlen Collection)

Apparently a manger scene on Ninth Street, looking west towards the Cloth Building with Mill No. 1 behind it, 1951

(Courtesy Duke University - Lewis J. McNurlen Collection)

Looking west at the non-connected Main and Mulberry Streets in front of the mill, 12.05.51

(Courtesy The Herald-Sun)

Two Watchmen at Erwin Mills, 05.27.53.

(Courtesy The Herald-Sun)

In 1962, control of the mills shifted from Abney Mills to Burlington Domestics (soon to be Burlington Industries.) Manufacturing continued during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. At some point during this era, the towers on Mill No. 1 were shortened from 4 stories to 2 stories; although one explanation given for the shortening is that the workers felt the towers too "prison-like" I find this a doubtful impetus for the considerable expense. (During this same era, one of the two towers at Golden Belt was shortened as well.)

Mill No. 4 in 1977

(Courtesy Old West Durham)

Front gate of Mill No. 4, 1977

(Courtesy Old West Durham)

In 1986, Burlington shuttered the plants and sold them to the J.P. Stevens Co., and the factory closed shortly thereafter. Clay Hamner and Terry Sanford, Jr. purchased the property from JP Stevens. Having experience with adaptive reuse in Durham from their conversions of Brightleaf Square to retail and office space in 1982 and 500 North Duke St. in condominiums in 1984, they converted Mill No. 1 and the old office building into a combination of office and residential space. However, their adaptive reuse stopped there, as they demolished all other buildings associated with the mill, including the entirety of Mill No. 4

In 1988, they began construction of a 10 story 236,000 sf office tower with retail and office space extending to the north and west of the tower. It was slated to be the first of several such developments to be built on the then-vacant space once occupied by the mill as well as 10th, 11th, and 12th streets.

Construction of the office tower and associated retail space, 02.01.89. You can notice that the Durham Freeway empties into Erwin Road toward the right lower corner of the picture.

(Courtesy The Herald Sun)

The tower would house First Union and Wachovia, respectively, as anchor tenants. It was purchased for $38 million by SCI Real Estate from Durham developers Clay Hamner and Terry Sanford, Jr. in 1999.

Today, the Mill No.1 contains a mixture of apartments and offices - including quite a few Duke offices. The original office building also contain a number of office suites. The Erwin Square tower, I believe, is a general office tower at this point. Suites around the base contain a number of retailers and restaurants.

Erwin Mill No. 1, 04.12.09.

Erwin Mill office building, 04.12.09

Similar location to panorama of Mills No. 1 and No. 4, above, 04.12.09

Erwin Square, site of Erwin Mill No. 4, 06.13.09

While I'm happy that the Erwin Mills office building and the Mill No. 1 main building were preserved, I can't help but bemoan the loss of Mill No. 4 and all of the other associated buildings. The opportunity existed here to create something on the scale of the American Tobacco Campus. Admittedly, this would have been more challenging in 1989 than 10 years later, but given that part of the mill was preserved, I'm not sure why the entirety wasn't. Floorplates seen as too large? I don't know.

It's hard to get too excited about Erwin Square, that very-1980s new construction. Even if the "big field" is at some point developed, it's hard to imagine Erwin Square feeling very integrated with the rest of Ninth Street. To me, one feature says it all about the office tower/retail building - there is no sidewalk that connects the building to the sidewalk on West Main St. It feels like it got lost on the way to RTP/Cary/Glenwood Ave. to me. I know there are two Bakatsias restaurants over there, but I somehow always forget they, or anything else retail exists in that place - and I think that has a lot to do with the building and the site. Ah, what could have been.

Update: In February 2012, Crescent Resources broke ground on the construction of a 303 unit multifamily (apartment) development on a six acre portion of the former Erwin Mill No. 4 site.

Looking southeast from ~Station 9.

Requisite gauzy watercolory rendering that looks way more historic than the final product will. (Nothing particularly against this development - just wish architects wouldn't make these renderings so fake - with the mature trees, etc.)

Comments

Submitted by JSchelp (not verified) on Wed, 11/23/2011 - 3:18pm

Stunning, Gary. An amazing collection of old photographs, street maps, postcards and more recent pictures for Mill No 4. 100 houses and buildings for just one neighborhood in Durham. A resource that generations to come will enjoy.

Submitted by Andrew Edmonds. (not verified) on Mon, 2/20/2012 - 11:40am

Earth-moving has commenced on this parcel in February 2012 for "Circle Ninth Street":

http://www.circleninthstreet.com/

http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/crescent-resources-begins-circl…

303 Unit Luxury Apartment Community under construction in Durham, N.C.

DURHAM, N.C., Dec. 5, 2011 /PRNewswire/ -- Crescent Resources, LLC completed its acquisition of a six-acre site adjacent to Ninth Street and the historic Erwin Mill building today. Construction will begin immediately on a landmark 303-apartment home community, Circle Ninth Street. The first apartments are expected to be complete in the fall.

"This irreplaceable site is ideal for multifamily residential with its close proximity to the entertainment and dining venues in the Ninth Street District, Whole Foods, Duke University and Duke's medical campus that employs more than 32,000 people," said Brian Natwick, president of Crescent Resources' multifamily division. "Circle Ninth Street will offer a unique lifestyle that allows residents an opportunity to work, play and live all within easy walking distances."

The architectural style of Circle Ninth Street was inspired by the existing historic Erwin Mill building and the previous factories and warehouses in the area. Those styles will be incorporated across several distinct building types to provide a neighborhood feel and context for the Ninth Street community. A mix of reclaimed industrial materials and clean modern aesthetics will highlight the interior spaces. Circle Ninth Street is designed to meet Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification requirements from the U.S. Green Building Council.

The arrangement of the four-story buildings will provide several private outdoor amenity areas, including a central lawn, community park, dog park, and pool and fitness courtyard. The courtyards will be interconnected, and the streetscape areas are designed for urban, walkable connections. Resident amenities will include a lounge, wireless cafe, gaming room, demonstration kitchen, group study library, business center, screening room and fitness center.

Cline Design Associates of Raleigh is the project architect and landscape architect. Historical Concepts, based in Atlanta, serves as the design consultant. John R. McAdams of Durham is the land planner and civil engineer, and Vignette Interior Design of Charlotte is the interior designer. State Building Group of Charlotte has been named the general contractor. Kettler Management of McLean, Va., will serve as the property manager.

The $47 million project is being financed by an equity investment from Crescent Resources and financing through U.S. Bank N.A. and Pearlmark Real Estate Partners LLC. Crescent has started construction on four multifamily communities in 2011, and this is the company's third equity investment in a multifamily project this year.

More information is available at LiveNinthStreet.com. The website also provides a signup form for people who wish to receive project announcements and leasing information.

About Circle

Circle was inspired through extensive review and analysis of current industry trends and marketplace needs. The progressive Circle communities are places where neighbors connect. In addition to presenting a new breed of apartments that people are excited to live in, Circle developments are also infused with the exceptional quality and customer-oriented features that have become Crescent hallmarks. Visit www.liveinthecircle.com for more information.

Crescent's existing multifamily communities include Circle at South End in Charlotte, N.C.; Circle at Concord Mills in Concord, N.C.; Circle at Crosstown in Tampa, Fla.; and Circle at Bartram Park in Jacksonville, Fla. In addition to Circle Ninth Street, multifamily communities under construction include The Venue at Cool Springs in Nashville, Tenn.; Circle West Campus in Austin, Texas; and Gallery at Cameron Village in Raleigh, N.C. Crescent's planned multifamily communities include Circle SouthPark in Charlotte; and Circle Bayshore in Tampa; and four additional developments planned to start construction in 2012.

About Crescent Resources

Crescent Resources is a real estate development company with interests throughout the southeastern United States. Based in Charlotte and established in 1969, Crescent Resources is known for its single-family, multifamily and resort residential communities. Crescent also develops business and industrial parks and shopping centers. Visit www.crescent-resources.com for more information.

Submitted by Joseph Sparks on Wed, 11/5/2014 - 6:50pm

My father was a carpenter here and my mother worked as a sheet seam sticher for several years in the mid 1960s.

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.