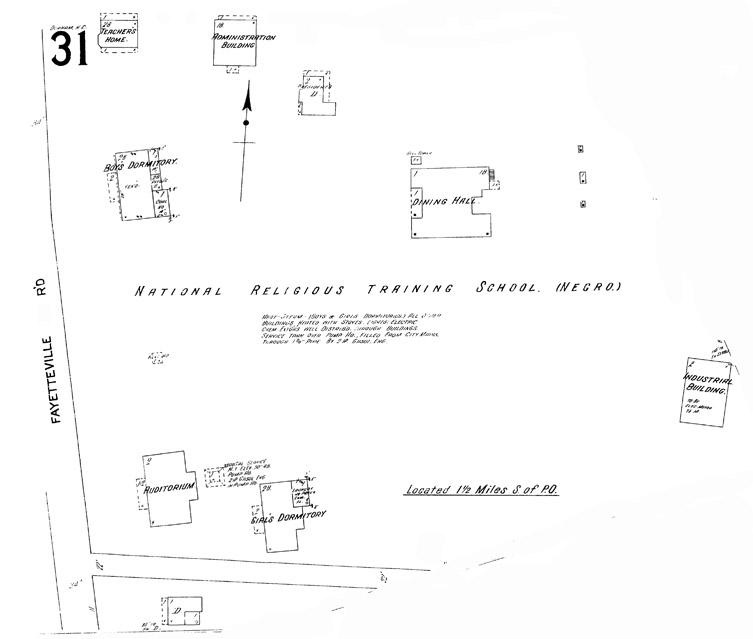

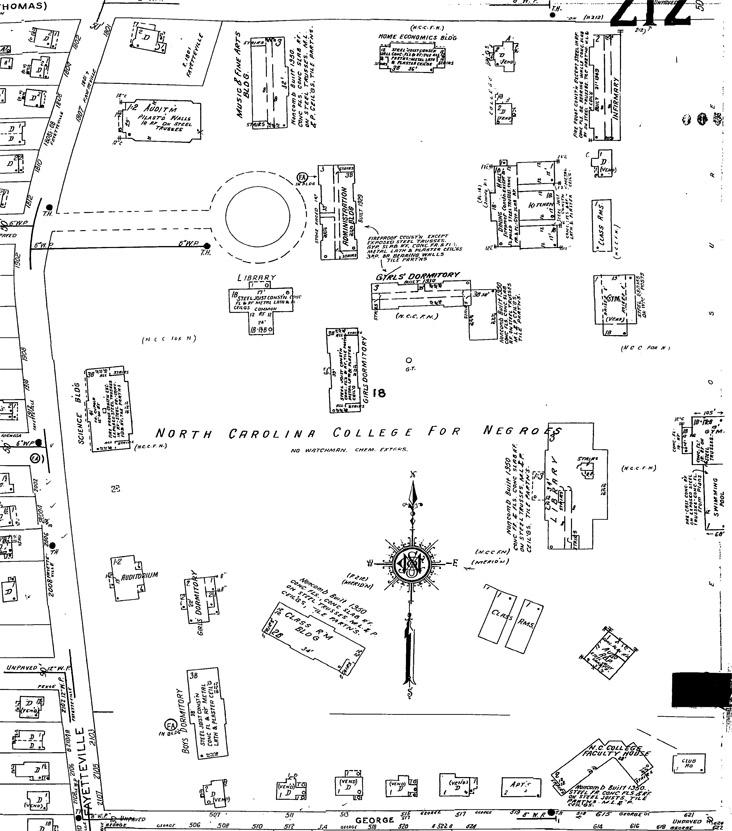

Sanborn Map of the National Religious Training School and Chatauqua, 1913

The establishment of what would become North Carolina Central University can accurately be described as the product of the dedication of James E. Shepard, who embarked upon seemingly sisyphean effort, in the early years, to establish the school.

Shepard's labor of love was born out of the Baptist religious tradition; Shepard had moved to Durham from Raleigh with his father, Augustus Shepard, who became minister of the

https://opendurham.org/buildings/white-rock-baptist-church in 1901. James Shepard was born in 1875, and had graduated from Shaw University with a degree in Pharmacy by the time his father moved to Durham.

The elder Shepard was already established as an important figure in the Baptist faith, having organized the Baptist State Sunday School Convention of North Carolina in 1872, and served as a representative to the American Baptist Publication Society. Despite his degree in Pharmacy, the younger Shepard elected to pursue ministry as well, and began working nationally and internationally in the establishment of Sunday Schools - traveling throughout Europe and Africa in 1907.

Upon his return, James Shepard began work to establish an institution - one that would provide a theological/religious education to the African-American community - dedicated to training more missionaries and Sunday School teachers. He put together the prospectus for a school in 1908, and initially planned to build the campus on 280 acres at Irmo-South, 10 miles from Charleston, SC, on the site of the former South Carolina Industrial Home. He also considered a 20 acre site located near Hillsborough, NC before settling on Durham as the site for the school.

Shepard began to travel to raise funds for his endeavor; after raising $1000, he chartered the school as a private institution in 1909, giving it the lengthy-but-descriptive name of "The National Religious Training School and Chautauqua for the Colored Race."

The Merchants' Association of Durham, a forerunner of the Chamber of Commerce, was supportive of Shepard's efforts and persuaded Brodie Duke to donate 20 acres off of Fayetteville Street to the fledgling institution. By July of 1909, the curriculum

had expanded to include coursework in "agriculture, horticulture, and domestic science," which Jean Anderson postulates were concessions to the various white backers of the school, looking to maintain a blue-collar African-American labor pool. Perhaps - although I'm not sure that people so-motivated would back a college for African-Americans in the first place, as any advanced education hardly helped keep African-Americans in the most menial of positions.

Anderson notes:

Mass meetings to stimulate interest brought prominent speakers: DA Tompkins, Dr. James H. Dillard and Rabbi Abram Simon among them. Julian Carr was treasurer of the organization, Shepard president, and [Dr. Aaron]

Moore secretary.

The school opened for business on July 5, 1910.

Shepard struggled to raise funds to support the school. Repeatedly applying to the General Education Board, he faced rejection, as the Board saw his endeavor as a "largely one-man enterprise" and criticized the effort as superfluous, saying "it is difficult to see what place this institution could fill that other institutions do not." Leslie Brown postulates that the GEB's rejection of Shepard's application was due to the intellectual ambition of his program - i.e., the effort to move beyond the manual training model preferred by most whites - contrasting the "Hampton-Tuskeegee Model" of manual training with the preparation of the "Talented Tenth for leadership" as offered by schools such as Fisk and Howard.

It is equally likely that Shepard's initially shoestring efforts were not confidence-instilling. The school shut down due to lack of funds in 1915; it was "sold and reorganized as" the National Training School. A host of private philanthropists helped support the school during lean early years. Margaret Olivia Slocum Sage helped support the school, as did Woodrow Wilson.

The original campus consisted of mostly Greek Revival frame structures arrayed around a 'bowl' in the center of the campus, including an administration building, auditorium, dining hall, girls' dormitory, and boys' dormitory.

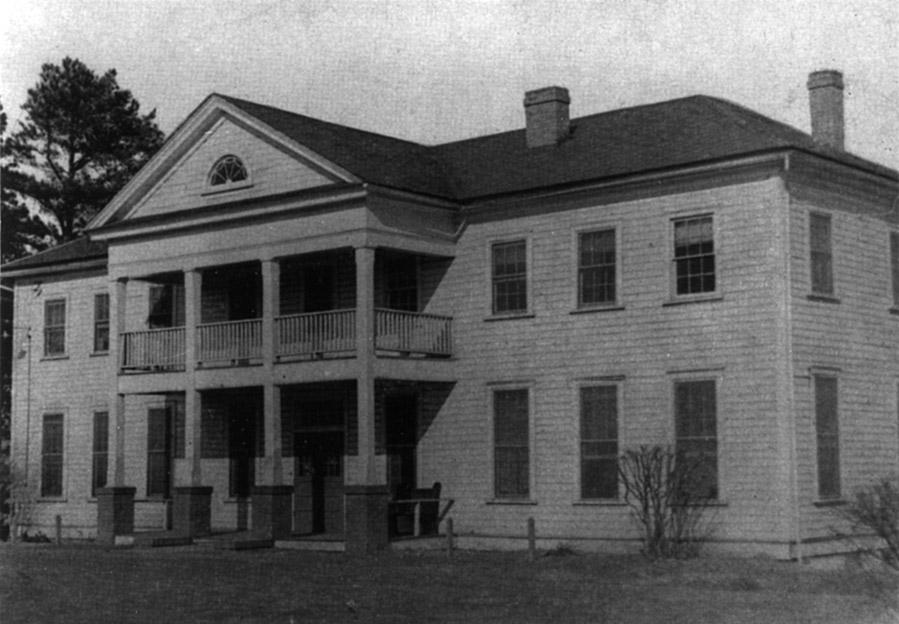

Girls' Dormitory

35.973827, -78.900505

(Courtesy Duke Rare Book and Manuscript Collection)

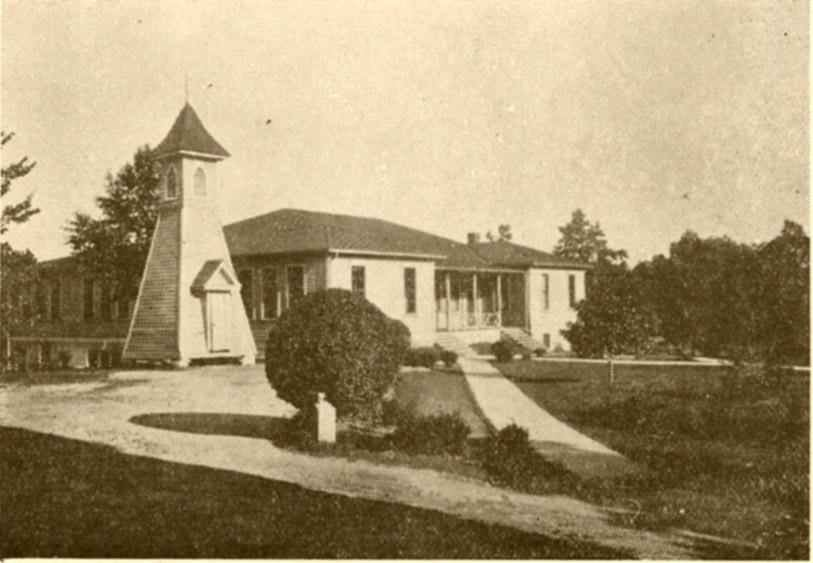

The Auditorium, with the Girls' Dormitory in the background, 1922.

35.974014, -78.900929

(Courtesy Duke Rare Book and Manuscript Collection)

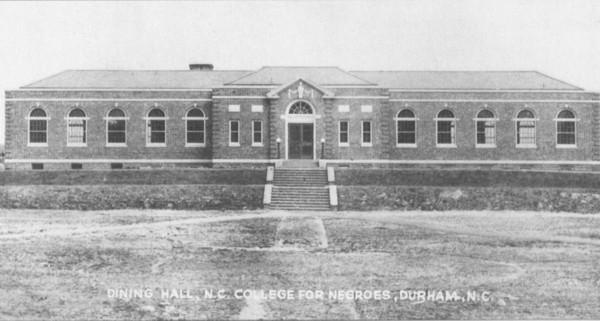

Original Dining Hall, 1922.

35.974745, -78.899952

(Courtesy Duke Rare Book and Manuscript Collection)

Original Administrative Building.

35.975078, -78.900690

(Courtesy Durham County Library / North Carolina Collection)

"Campus Scene" 1922. I'm not sure of the viewpoint - but perhaps behind the Girls' dormitory, looking west. I think the depression is the 'bowl' (Greek bowl?) in the center of NCCU's present campus.

(Courtesy Duke Rare Book and Manuscript Collection)

Boys' Dormitory, 1922.

35.974813, -78.900952

(Courtesy <a href="http://www.herald-sun.com">The Herald-Sun Newspaper</a>)

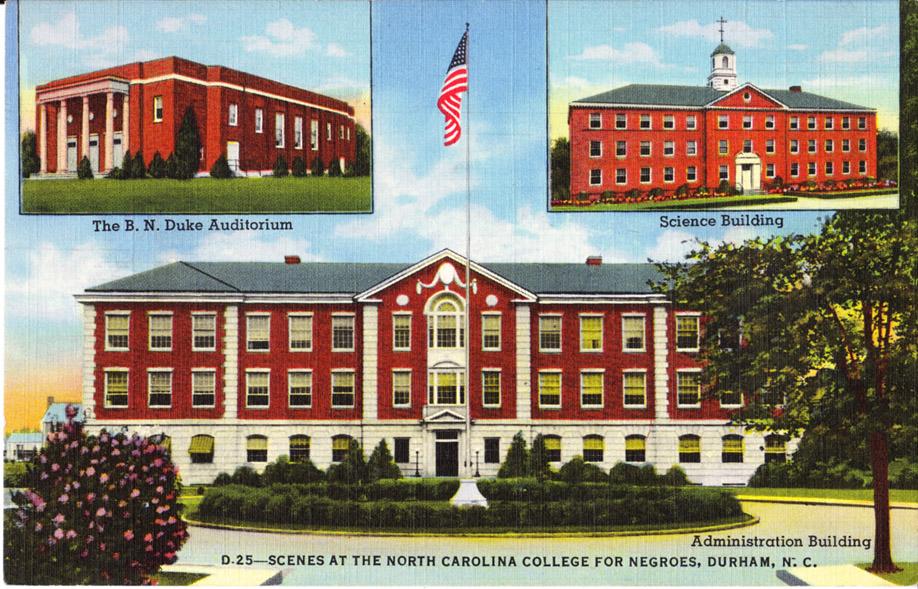

In 1923, the North Carolina State Legislature appropriated funds for the purchase and operations of the school, and the school was renamed the "Durham State Normal School." By 1925, it was renamed the "North Carolina College for Negroes" with a focus on liberal arts education and preparation of teachers and principals for secondary schools.

The inclusion into the UNC system provided the funds to significantly upgrade the facilities on campus, authorized by the General Assembly in 1927. Per NCCU's official history, the support of Governor Angus McClean was an important factor in the appropriation, and the financial support of Benjamin Duke and "contributions of the citizens of Durham" allowed the facilities expansion to move forward.

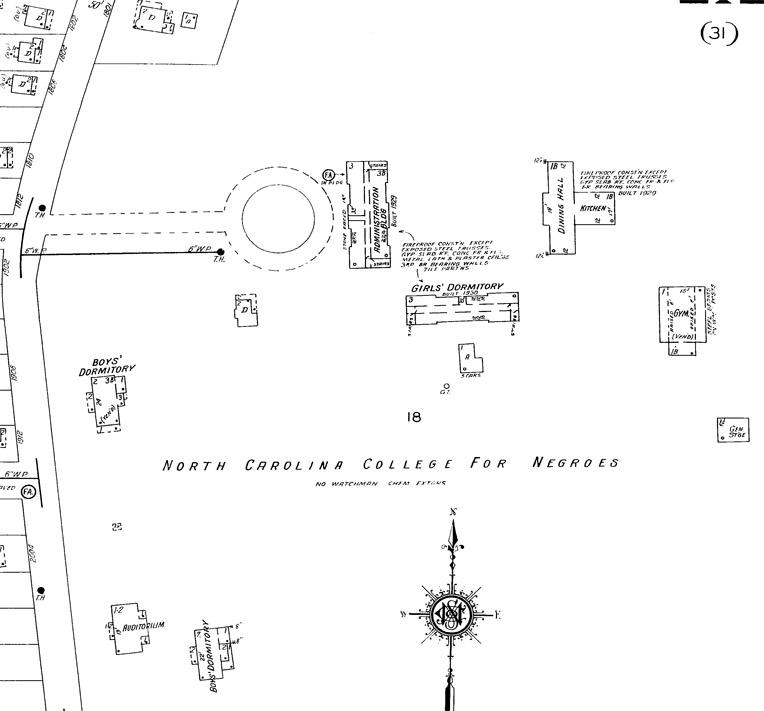

Initially, this was done while retaining some of the original structures on campus; notably the Boys' Dormitory, the Auditorium, and the original Girls' Dormitory were retained, while new masonry structures designed by architects Atwood and Nash, replaced the Administration Building and Dining Hall, and provided a new Gymnasium and Girls' Dormitory.

Campus Map - 1937, showing the remaining older structures towards the southwest corner, and a new cluster of structures arrayed around the new circular drive off of Fayetteville Street.

Boys' Dormitory, 1940s -

New Administration Building, now called the Hoey Building, 1929

35.975481,-78.899767

New Dining Hall, 1930

35.975497,-78.898915

The physical campus expanded again in the late 1930s with the addition of the BN Duke auditorium - named after the College's largest private benefactor to that date and the Science Building - which was erected at the location of the original Boys' Dormitory. The Science Building was designed by Public Works Administration architects, in a similar style to the Atwood and Nash Buildings.

(Courtesy UNC)

The College was accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools as an “A” class institution in

1937 and was admitted to membership in that association in 1957.

Notably, the Law School was opened in 1940, admitting 4 students in its original class, and the first female students in 1944. (UNC would not admit African-American students to its law or medical schools until 1951.)

In 1947, the NC state legislature changed the name of the school to "The North Carolina College at Durham." In October of that year, Shepard, who had been the longtime president of the college, died.

Between 1937 and the mid-1940s the campus also added new Girls' and Boys' dormitories, an auto repair education building, and a Library. The campus website notes these structures as added in 1937; however, they do not appear on the 1937 Sanborn map.

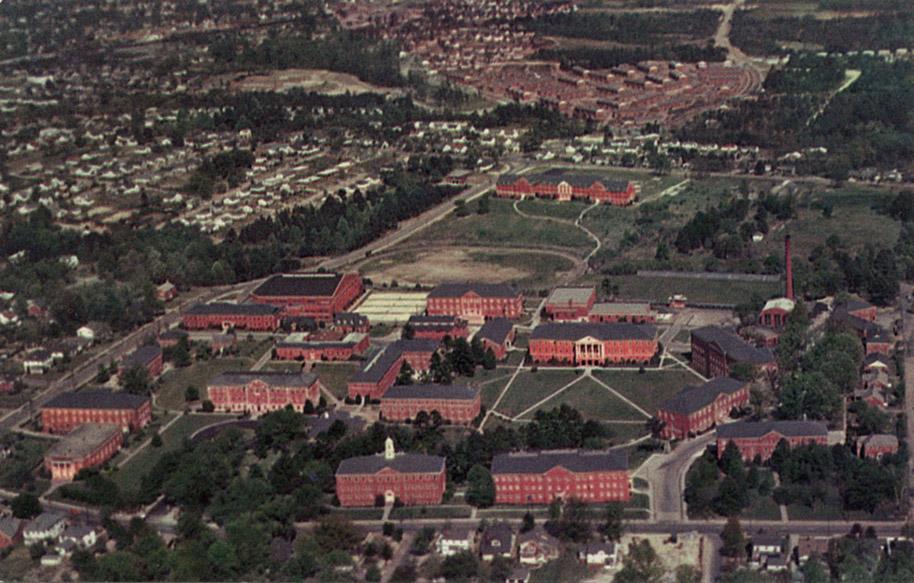

Bird's Eye aerial, 1940s, looking northeast, showing the growth of the campus over the late 1930s and early 1940s:

(Courtesy <a href="http://www.herald-sun.com">The Herald-Sun Newspaper</a>)

Yellow: BN Duke auditorium (late 1930s)

Red: Administration Building (1929)

Dark Blue: Girls' Dormitory (1930)

Purple: Dining Hall (1930)

Pink: Home Economics Building

Royal Blue: Girls' Dormitory (~late 1930s)

Orange: Science Building (1937)

Light Green: Original Auditorium (1910)

Dark Green: Original Girls' Dormitory (1910)

Aqua: Boys Dormitory (late 1930s)

Light Blue: Gymnasium with single story swimming pool (1940) to its right.

The campus expanded greatly again in 1949-1951, with the addition of a new Library, a new classroom building, a Faculty House, a Music and Fine Arts Building, an Infirmary, a new gymnasium, and the Chidley Residence Hall at the eastern edge of campus.

From "Negro Durham Marches On" - 1949:

1950 Sanborn Map of the college, showing the ongoing physical expansion.

Bird's Eye aerial, looking east, 1950s.

(Courtesy Durham County Library / North Carolina Collection)

Red: New Library

Yellow: New Classroom Building

Purple: Faculty House

Blue: Music and Fine Arts

Light Blue: Infirmary

Pink: New Gymnasium

Green: Chidley Residence Hall

The last of the original buildings - the auditorium - is still standing in this picture. In 1956 it was torn down for the Biology building.

Postcard aerial, mid 1950s. Note the construction of McDougald Terrace in the background, with extension of Lawson Street towards Durham Tech underway.

(Courtesy UNC)

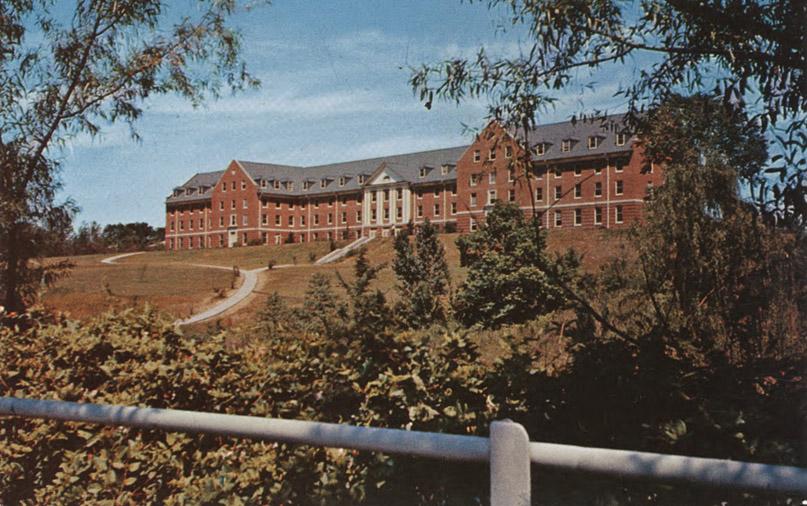

Chidley Residence Hall.

(Courtesy UNC)

In 1969, the College was renamed North Carolina Central University, and in 1972, became "a constituent institution of the University of North Carolina system. On July 1, 1972, the state’s four-year colleges and universities were joined to become The Consolidated University of North Carolina, with 16 individual campuses, headed by a single president and governed by the University of North Carolina Board of Governors."

The university has continued to expand over the second half of the 20th century - moving first beyond its north south boundaries of East Lawson Street and George Street, continuing to expand eastward towards Alston, and more recently, expanding westward across Fayetteville into the College View neighborhood.

Aerial view, 02.01.89

(Courtesy <a href="http://www.herald-sun.com">The Herald-Sun Newspaper</a>)

1929 Administration Building (Hoey Building)

Late 1930s Library Building, 05.24.11

35.975102,-78.900186

Late 1930s BN Duke Auditorium, 05.24.11

35.975956,-78.900641

1937 Science Building, 05.24.11

35.974686,-78.900932

1956 Biology building, 05.24.11

35.974113,-78.900845

1930 Girls' Dormitory, 05.24.11

35.975114,-78.899387

1930 Dining Hall, 05.24.11

Late 1930s Boys' Dormitory, 05.24.11

35.973425,-78.900351

Chidley Residence Hall - seriously obstructed, 05.24.11

35.974845,-78.894771

1950 Infirmary Building, 05.24.11

35.976099,-78.89841

1950 Music and Fine Arts Building, 05.24.11

35.976112,-78.900108

Taylor Education Building, 05.24.11

35.974924,-78.89789

One of the newest additions to NCCU (and one of the more architecturally interesting buildings on campus, particularly among the new stuff - Pearson Cafeteria, 05.24.11)

35.976085,-78.899128

Comments

Submitted by kris (not verified) on Tue, 8/16/2011 - 2:00am

The 1930 Girls' Dormitory is called Annie Day Shepard Hall. At least, it was in 1990 when I stayed there for a summer program for 5 weeks. Only the lounge was air conditioned, so that's where everybody went.

Submitted by Murray L. Edwards (not verified) on Sun, 4/6/2014 - 7:36pm

Thanks for this wonderful historic view of the initial structures of NCCU's buildings. Nothing short of great! This has inspire further.

Submitted by Anonymous (not verified) on Tue, 8/16/2011 - 2:00am

Great post again. Excellent work and pictures (sorry Anon #2!)

Submitted by Anonymous (not verified) on Tue, 8/16/2011 - 2:00am

I haven't been able to see any photos posted to this site in about a week. Obviously other people aren't having the same problem, but I would like to know if anyone else is.

Submitted by Anonymous (not verified) on Tue, 8/16/2011 - 2:00am

Excellent post! I had seen old photos of the campus but never knew exactly where the first-generation buildings stood. Your maps are very helpful.

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.