Bacon Rind Bridge over the Neuse River on US Highway 15, looking west-southwest, July 7, 1942 (photograph by Albert Barden, Courtesy of State Archives of North Carolina - collection online via flickr).

A series of photographs from this summer 1942 crash - part of the fantastic Albert Barden Collection digitized by the State Archives and fascinating in their own right - triggered a look back at historical maps, a dive into old newspapers and property records, and a bit of boots-on-the-ground reconnaissance at the edges of what is now Falls Lake.

That familiar reservoir and recreation site is a relatively recent creation, formed from the damming of the Neuse River at Falls, which flooded the low banks of the waterway and its tributaries upstream in the early 1980s. A careful look at contemporary road patterns or an observant eye hiking lakeside trails reveals a network of former roads and hints of other infrastructure that served farming communities along the river as well as people passing through. Decades prior to the flooding of Falls Lake, before the construction of I-85 in the late 1950s, one of the primary paths in and out of Durham crossed the Neuse at the wonderfully named Bacon Rind Bridge.

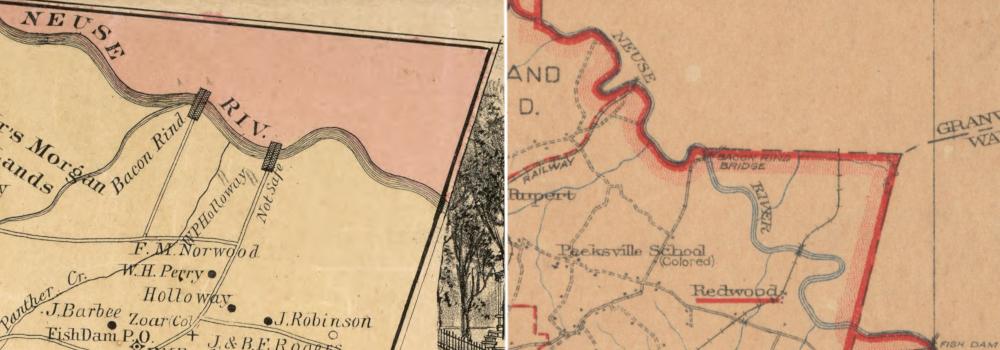

Labeled on maps and referenced in local media for seven decades, Bacon Rind Bridge crossed the Neuse River just below Ellerbe Creek (at left: fragment of 1887 Cram-Johnson map of Durham County, printed by The Tobacco Plant newspaper, online via Library of Congress; at right: fragment of 1920 Durham County map, Duke University Special Collections, online via Digital Durham).

The source of the name Bacon Rind remains unclear; it does not appear that the term ever corresponded to a nearby community on either side of the river. In all likelihood, the first crossing at this location was constructed when the land on both sides was part of the vast holdings of the Bennehan-Cameron family. These parcels - totalling over 1,000 acres in what was then Wake and Granville Counties - were acquired in the 1830s by Thomas Bennehan (son of Stagville founder Richard Bennehan, whose property would pass to brother-in-law Duncan Cameron when he died without offspring in 1847).

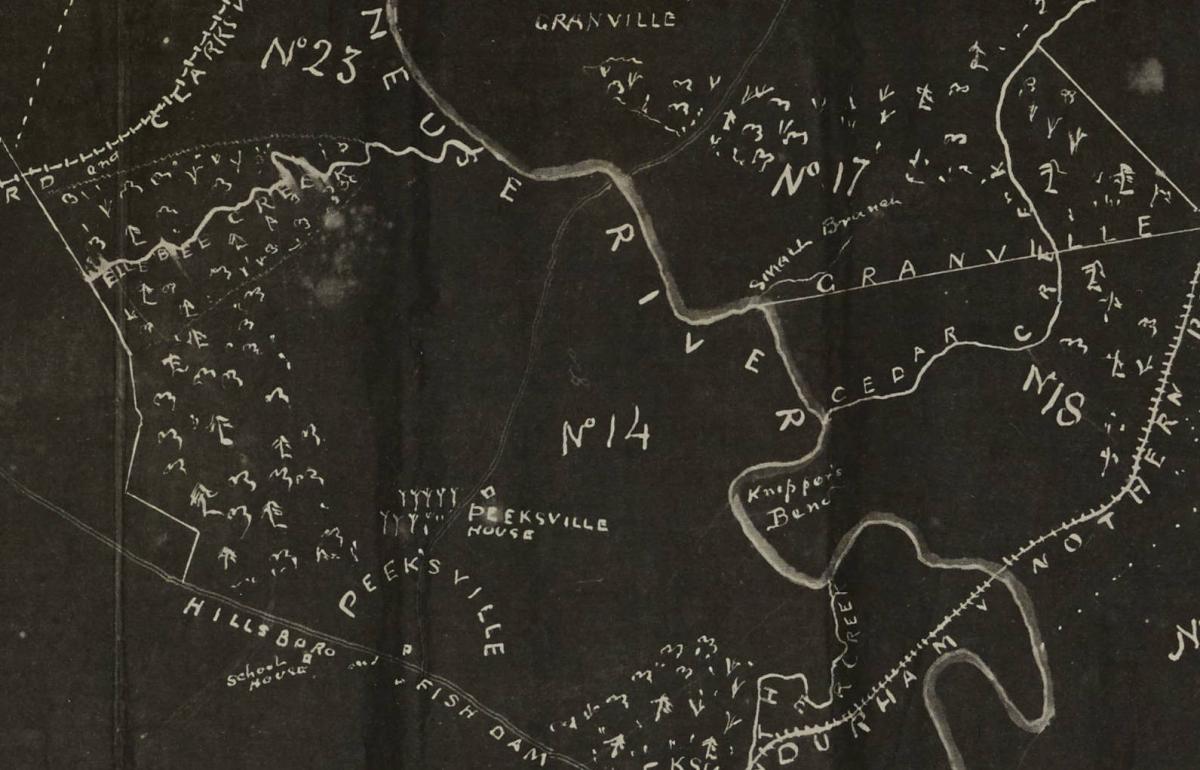

Fragment of the 1890 survey map of land owned by Paul Cameron (part of the Cameron Family Papers, Wilson Library, UNC). Note the faint roadway running roughly north-south up the center from Peeksville (more often rendered Peaksville), crossing between the two words for the Neuse River.

Prior to the Civil War, the creation of Durham, and its rapid growth, a single, older bridge across the upper reaches of the Neuse seems to have been sufficient. All roads quite literally led to Fish Dam (in some sources Fishdam), where a post office was established as early as 1826, servicing a main point en route between older towns like Hillsborough and Oxford.

Fragment of Fendol Bevers' map of Wake County, 1871 (State Archives of North Carolina, online via North Carolina Maps). Note the town names on the roads converging at Fishdam, and the absence of a crossing further northwest. This corner of Oak Grove Township would be transferred to newly formed Durham County a decade later.

The explosion of Durham was surely among the causes for building what would become the Bacon Rind Bridge at this location. A March 1880 issue of The Tobacco Plant newspaper reported on a meeting of some of the young town's leading figures, who resolved unanimously that improvements to roads connecting Durham to its suppliers of agricultural products in the surrounding countryside were essential to its prosperity. Among the key transportation investments they enumerated was a "bridge at Peaksville" - a reference to the community just southwest of the river through which an important road northeast out of Durham already ran. Three of the men - W. A. Lea, J. G. Lunsford, and I. M. Reams - were appointed delegates to citizens and officials from neighboring Wake and Granville Counties to drum up popular support and joint investment.

While the results of that specific delegation's efforts have yet to be established, another issue arising that year (and recurring throughout the decade) reinforced the importance of the Peaksville bridge proposal: the vital crossing at Fish Dam was subject to frequent flood damage. It seems likely that when that vulnerable bridge - and the jurisdiction to appropriate funds for its repair - fell just beyond the initial eastern border of newly formed Durham County in 1881, the conditions finally aligned to build Bacon Rind as a controllable backup and eventual replacement. The exact date of construction is unknown, but it was apparently a wooden structure erected prior to the printing of the 1887 map excerpted above. The new bridge immediately became critical commercial and community infrastructure, with county funds allocated to its upkeep and even an apparent emergency plan....

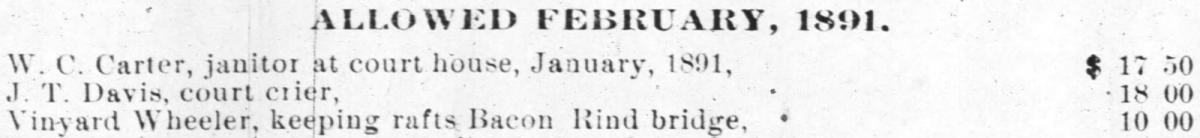

Excerpt from account of expenses approved by Durham County Commissioners for 1891, including $10.00 to a local named Vinyard Wheeler for maintaing rafts at Bacon Rind Bridge (printed in the December 15, 1891, edition of the Durham Globe, online via NCLive.org).

Once in place, the bridge was apparently heavily used. By the 1910s, reports on its condition sounded much like those for the earlier structure at Fish Dam. Both were among targets in an expanded county roads budget that would see wooden structures replaced with concrete and steel. Commissioners let a contract in December 1913 to Virginia Bridge & Iron Company based in Roanoke to build two bridges for just under $11,000 - one at Little River on the road to Stagville and the other here. They apparently didn't move fast enough to prevent closure of the increasingly rickety old bridge in the heavy rains of summer 1914, but the structure pictured at the top of this page was apparently up by the end of that year.

This turned out to be tricky timing for building fixed infrastructure like a bridge, as both automobile usage in general and traffic to Durham in particular would greatly increase in the years immediately thereafter. Boosters on both sides of the Neuse - by now Durham and Granville Counties - successfully lobbied for the route via Bacon Rind to be paved in the 1920s as the new main highway to Oxford, christened NC-75 by the end of the decade.

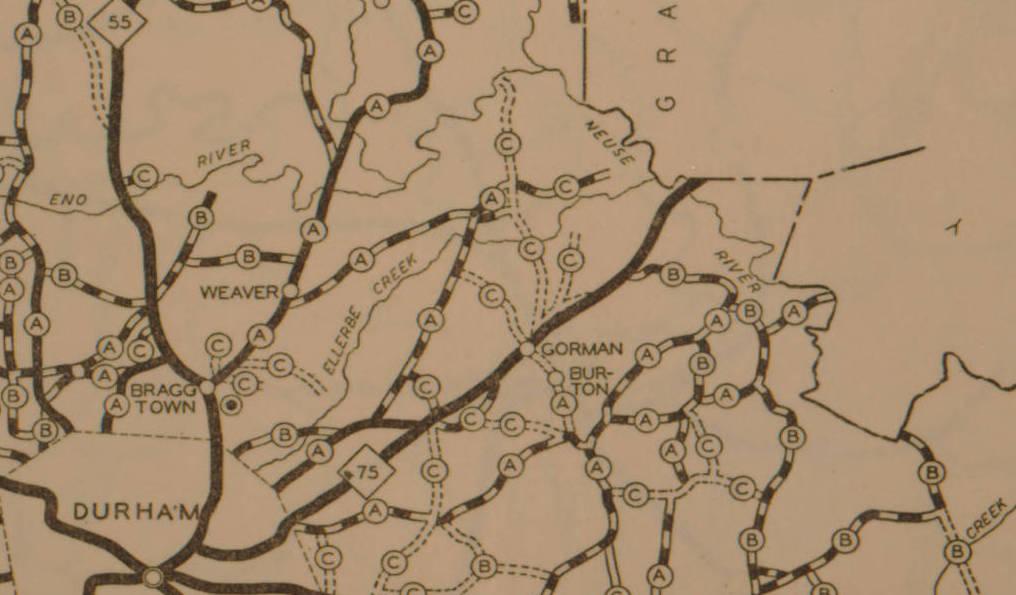

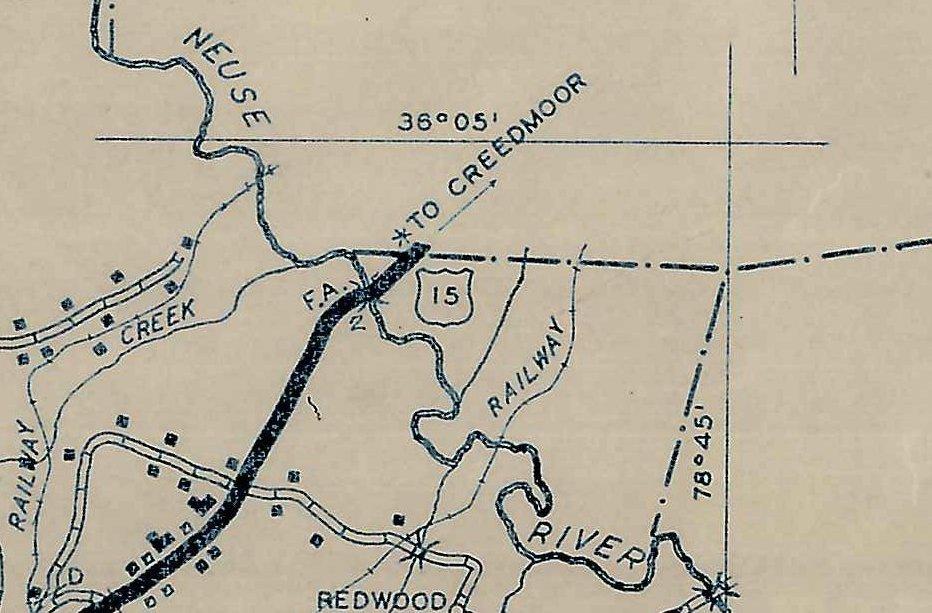

Fragment of a 1930 NC Department of Transportation map for Durham County, showing the route from town northeast to the Neuse and Granville County as the new, hard surface NC-75 (State Archives of North Carolina, online via North Carolina Maps).

With federal funding expanding the US Highway system, this section and much of NC-75 had been rebranded US-15 by the mid-1930s. That name would stick for just over two decades before I-85 was opened, but it already signalled that decision-making authority regarding development in this still-rural corner of Durham County had shifted - first to Raleigh and then to Washington.

Closeup from 1936 NCDOT Durham County map, showing US-15 and its Neuse River crossing at Bacon Rind Bridge (State Archives, online via North Carolina Maps).

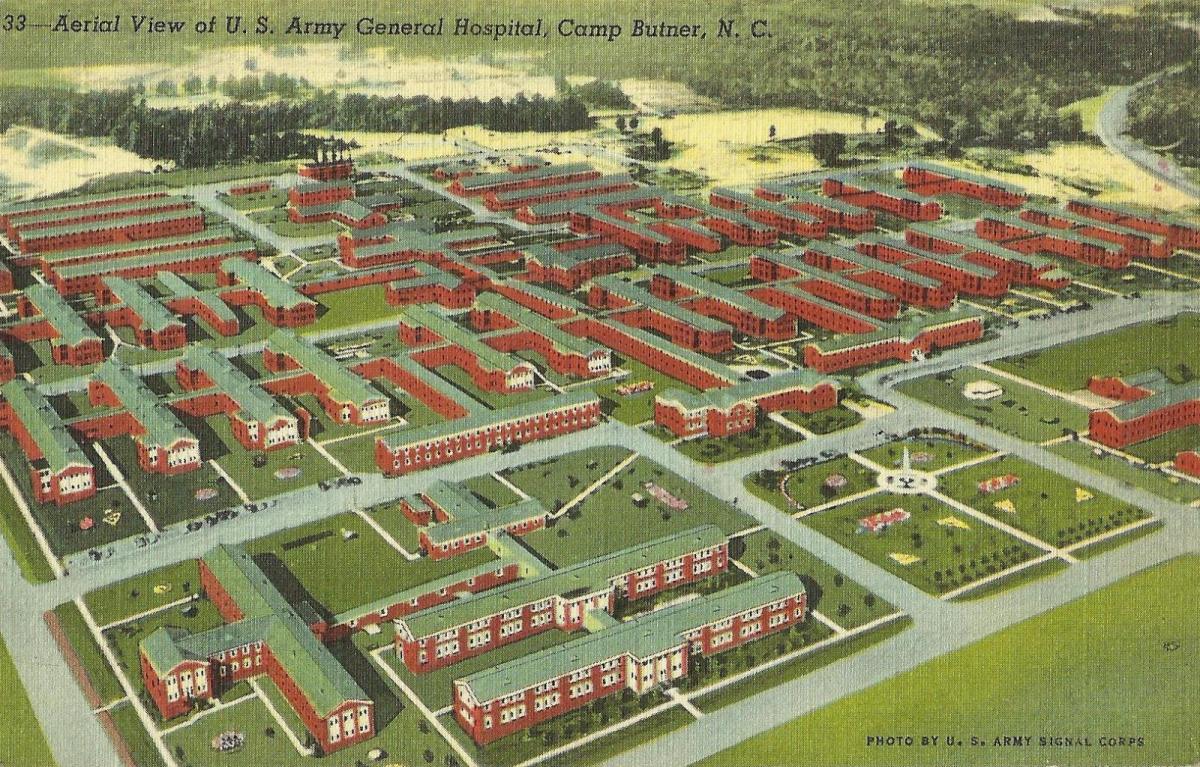

It would take one more, major federal level decision to cardinally transform the traffic streaming across Bacon Rind Bridge and set the stage for the crash that began this piece: the 1941 choice to locate a major military installation in parts of Granville, Durham, and Person County, under rapid construction from early 1942 after the US entered the Second World War - Camp Butner.

Aerial view of US Army General Hospital, Camp Butner, NC (Massengill Postcard Collection, State Archives).

We are in need of a whole host of new pages about places transformed - many erased - by the construction and operation of Camp Butner, but suffice it to say here that the stream of trucks carrying building materials, supplies, and later soldiers along US-15 to and from Durham trebled to unprecedented levels. This is where the terrain, shaped primarily by the nearby bend in the river (perhaps originally thought to shelter the bridge from the brunt of its flood torrents), became an urgent issue. Even before the big spike in traffic brought on by Camp Butner, the Bacon Rind Bridge featured in local newspapers as a site of periodic accidents, as the paved two-lane highway curved from its primarily southwest-northeast trajectory to cross the Neuse on a nearly east-west axis via this one-lane structure. Visibility would have been further obscured by the trees clustered along the river on either side of the roadway. In February 1942, the Durham Morning Herald informed readers of new, automatic safety signals installed at the bridge, which were supposed to activate when oncoming cars were approaching. In April, highway patrol publicized an "intensive campaign" to control transportation problems surrounding the camp, and focused on the Neuse River bridge as a site of long backups and dangerous incidents. By June, the Durham Sun reported on bids to build a replacement for the Bacon Rind Bridge to ease the worsening bottleneck along US-15, but that was still a plan for future execution.

So it was that on the morning of July 7, 1942, a small handful of passengers boarded the Richmond and New York-bound Greyhound Lines bus at the Durham station on Mangum Street (the new terminal on East Main would be opened that September). At the wheel was 27 year-old driver C. Rex Welsh, a father of three who lived in northern Trinity Park and had been working for the company at least two years. Exactly the same age, Henry Pope of Mebane probably hit the roads earlier that morning; he was a trucker for Burlington-based Barnwell Brothers, but may have operated out of their lot in Durham. Whatever his exact itinerary, it appears likely he had already taken a load to Camp Butner and begun his return journey by late morning.

The Greyhound liner was just a few miles into its trip, speeding through the countryside east of town and slowing for the curve to cross Bacon Rind Bridge at about 11am. Welsh would surely have seen Pope's truck as he navigated the bus through the tightly-confined steel corridor, assuming he would obey the rules of the road and common sense to brake before oncoming traffic. Perhaps Pope was under time pressure or thought the bus would clear the bridge entrance before his vehicle reached it. No such luck.

Judging by Barden's photographs from the scene, the Greyhound bus and Barnwell Bros truck collided just at the northeast end of the bridge. The truck operated by Pope appears to have glanced off the bus and into the footing of the bridge, causing significant damage. (Photos by Albert Barden, State Archives - online via flickr)

Miraculously, nobody was more than shaken up, but Pope's truck remained disabled on the bridge for long enough to snarl traffic for miles in either direction, and caused a commotion that drew farm workers from the surrounding area while police and transportation company officials tried to sort out the situation.

Looking south-southwest from the damaged end of the Bacon Rind Bridge, the roadway apparently closed off with a log pulled from nearby as onlookers decide whether to regard the scene or pose for Barden's camera. (Photo by Albert Barden - State Archives via flickr)

Barden would have turned on his heels from the previous photograph to shoot this image, looking east-northeast at the back of the wrecked bus. Note the line of vehicles headed towards Durham forming in the left background. (Photo by Albert Barden - State Archives via flickr)

It is not readily evident why Albert Barden was at the scene of this crash. The finding aid for the vast collection of his photos donated to the State Archives at his death in 1953 indicates he ran a commercial photography studio out of Raleigh. The prevalence of material apparently shot for corporate clients - particularly insurance companies - suggests he may have been dispatched to document the damage for subsequent claims.

Disentangling the Barnwell Brothers truck from the bridge apparently took hours, long enough for traffic to be rerouted north via the Flat River bridge and Old Oxford Highway. Seargant R. S. Harris of State Highway Patrol would report to journalists that "several thousand dollars" worth of damage had been done to Bacon Rind Bridge, and courts would ultimately lay the blame on Henry Pope for the crash - fining him $25 plus costs for reckless driving. If a new bridge was already in the works, the incident further heightened concern and calls for changes, starting with improved signals to alert and stop approaching drivers for alternating use of the one-lane crossing.

Barden was apparently dispatched again to photograph signal changes at Bacon Rind Bridge later in 1942. Facing northeast from the Durham side, this view demonstrates how the curving approach and trees would have screened visibility of oncoming vehicles. (Photo by Albert Barden - State Archives via flickr)

Looking southwest, this image appears to show clearing and earthworks already underway for the rerouted Neuse River crossing that would eliminate the curve to Bacon Rind Bridge (Photo by Albert Barden - State Archives via flickr).

By January 1943, the replacement bridge was in place, though restrictions on gasoline usage and non-military travel meant few civilians would see it before the end of the war. There was no love lost for the old Bacon Rind Bridge in coverage by the Sun, which dubbed the dangerous approach "dead man's curve." Apparently several other crashes had ended far less fortunately than the one Barden captured on film. Usage of the name "Bacon Rind Bridge" - already declining in favor of terms referencing the motorway across it - never seems to have stuck as a moniker for the new bridge, though it does appear a handful of times in newspapers into the 1950s.

It seems likely that the retired structure was quickly dismantled as scrap metal for repurposing amidst the war effort, but we have yet to confirm a demolition date. Interestingly, the Durham side of the dreaded S-curve approach to Bacon Rind got a new lease on life once the straightened US-15 roadway released it to the possession of neighboring landowner Thomas H. Brinkley. Originally from across the river in Granville County, Brinkley had purchased 250 acres of the former Peaksville tract belonging to Stagville owner Paul Cameron, still managed by his estate for decades after his death until the sale in 1935. That acquisition coinciding with the rapid changes in activity along the highway through the land described above, Brinkley was apparently wise on ways to both take advantage of passing traffic and control flood waters on his larger farm.

Aerial images of the Bacon Rind Bridge site - 1940 at left, 1955 at right (cropped from USDA aerial photograph collection, digitized by UNC Libraries, GIS Services). The elevated road bed from the straightaway before the curve to the former bridge was utilized as part of the embankment for a recreational lake built on the land of T. H. Brinkley. Another nearby, postwar private recreational project, the tip of the runway for an airstrip (now known as Lake Ridge Aero Park) can be seen at the bottom of the 1955 image.

Hopefully there will be another new page on Brinkley's Lake before long - newspaper ads from the 1960s and 70s indicate the owner sold fishing permits as a kind of admission charge. As intertwined elements of abandoned - but not wholly erased - infrastructure, the Bacon Rind Bridge and Brinkley's Lake were both sites of the on-foot exploration that accompanied composition of this article. Brinkley descendants were among landowners compelled to sell land condemned for the creation of Falls Lake in 1980-81. But much like the rerouting of US-15 failed to fully erase Bacon Rind Bridge, the existing lake seems to have resisted incorporation into the newer, larger one.

September 1991 aerial photograph showing I-85 crossing at Falls Lake. In addition to the still-largely enclosed remnant of Brinkley's Lake above the roadway to the left of center and the phantom of the old course of US-15 across Bacon Rind Bridge, the former course of the Neuse River remains in evidence. (Source: NCDOT Historical Aerial Imagery)

With the water low thanks to prolonged drought in late 2021, it was relatively easy to follow old farm roads on what is now the Falls Lake flood plain and NC Wildlife Game Land from the Mountains-to-Sea Trail just north of its passage under I-85. (*Please be respectful if you're inspired to visit this location, and heed the very clear *No Trespassing* signs posted by neighboring property owners*)

Looking east across the remnants of Brinkley's Lake, December 2021 (N. Levy).

Following the access road likely used by earlier fishing visitors, you reach a dropoff where water from the flooded convergence of the Neuse and Ellerbe Creek seems to have filled in a field that would have sat above Brinkley's Lake. The lake itself appears in the above photo as the lower, second body of water, with the remains of a stone embankment marking the small wooded island visible in the earlier aerial photos. A kind of berm breakwater that must have been used to form the arcing, northern shore of Brinkley's Lake - then holding water from flowing down to the river, now often submerged - can be seen beyond the island, exposed by the low water level.

Continuing south along the shores of this two-tiered lake, the former roadbed of US-15 as it approached Bacon Rind Bridge appears as an unmistakable ridge - however eroded - separated by a small finger of Falls Lake from the I-85 causeway.

Remains of the old US-15 roadway, looking east towards the site of Bacon Rind Bridge. The body of water at left was once Brinkley's Lake; the I-85 roadway is visible at right. (N. Levy, December 2021)

Overgrown with brush and littered with plenty of trash, this unnatural peninsula follows the same arc once decried as "Dead Man's Curve," eventually ending abruptly at the water. There the concrete footing of the former Bacon Rind Bridge remains, as do a crumbling line of supports further out into Falls Lake.

Ruins of Bacon Rind Bridge, December 2021 (N. Levy).

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.