THE COUNTRY LIFE: When, in the mid-1920s, R. J. Mebane from Greensboro and W E Sharpe from Burlington conceived an upscale development organized around a golf course and country club, they created one of America's earliest proto- types for a suburban commuter development that depended entirely upon the auto- mobile. Inspired by the local economic boom created by the tobacco and textile industries and the prospect of a new Duke University, the two entrepreneurs bought up farm and dairy land which had been worked by homesteaders since the early 19th century. In February 1926, they formed Mebane & Sharp, Inc., a non-stock, non- profit, entity that would create the new Hope Valley suburb, now Old Hope Valley. The new neighborhood was designed to be a gracious community removed from city congestion and pollution, which would include modern conveniences such as under- ground water and sewer mains, electricity, two paved main thoroughfares, architect- designed homes, a professional golf course, and a country club destined to become the hub of social life for the new community and for greater Durham. Other recreational amenities such as horseback riding, golfing, swimming, tennis and even hunt- ing were also advertised as health-giving activities one would be able to find in this ideal and stylish neighborhood. Because of these features and the distance from the city center, residents of the new development were promised not only a healthier lifestyle but even greater longevity.

The United States' involvement in the Great War had opened the American pop- ulation at large to an awareness of things European. The decade after World War I ended also saw the automobile, airplane, the radio and movies become commonplace, particularly in the United States. Different people reacted differently to these events and architecture did as well. Some architects wanted to find entirely new solutions appropriate to the modern industrial way of life which was fast changing the shapes of our cities and our lifestyles. They wanted this new modernism to be reflected in our buildings without reference to the past. Others found it even more important to retain, or recover, certain aspects of the past. The Arts and Crafts Movement, which became the collective name of this "movement" in England, began in the 1880s. It sought to regain from the past meaningful pre-industrial values in work and at home. Names such as John Ruskin, William Morris, and later, Edwin Lutyens, and C.E A. Voysey are among the designers and architects working in this vein whose names one might recognize. While Lutyens and Voysey sought to discover a true English archi- tecture, the starting point for their vocabulary had late medieval and Tudor roots. At the turn-of-the-century in England, the Garden City Movement began to take shape under the aegis of Robert Parker and Raymond Unwin. Unwin had attended Ruskin's lectures at Oxford and was inspired by Morris. Parker had an Art & Crafts training in architecture.

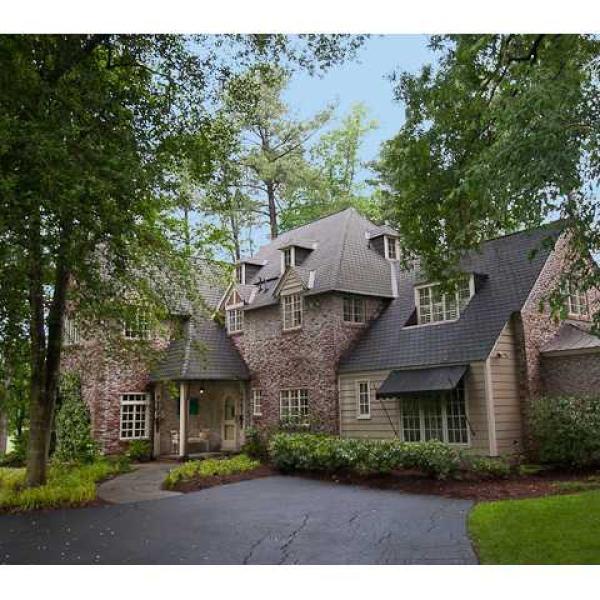

In the United States after WWI, many residential architects who preferred to work in a traditional way also looked to the late medieval and Tudor homes of our recent English allies for design ideas and a wholesome sense of place. Throughout the twenties and early thirties, Tudor style homes became the fashion. Society architects like John Russell Pope, Marcus Burrowes, and the Geo. B. Post & Sons firm of New York designed great manors for their wealthy clients. So popular was the style with the American upper and upper-middle classes, that it became known as "Stockbroker Tudor." The Tudor Revival style was not reserved exclusively for the rich, however. More modest designs were featured in ladies magazines and Tudor cottages could be bought ready-to-build from the Sears Catalog.

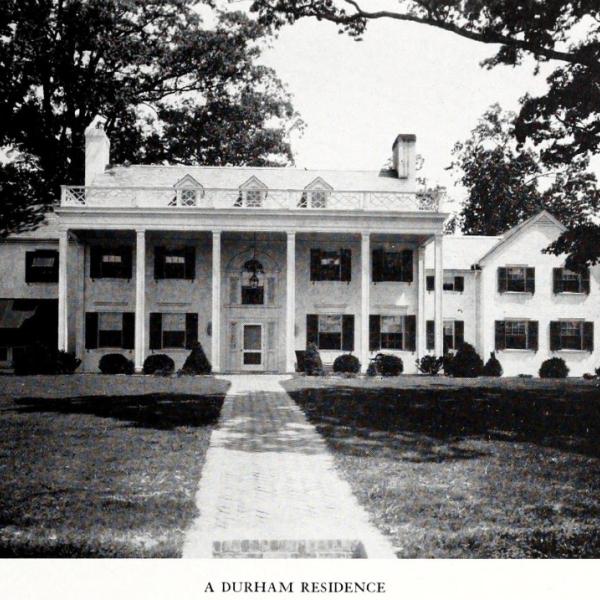

To attract people to Hope Valley and to set the desired tone and standard for the homes there, Mebane and Sharpe hired Durham's foremost residential architect, George Watts Carr, to design a handful of moderately sized, but ricWy detailed homes in the Tudor Revival and English Cottage styles. The developers desired to imbue their new neighborhood with an "Old English" feeling in keeping with the country lifestyle of England's leisured classes. However, it is important to note that alongside the assertion of tradition- al style, was the rapidly moving modernization which the very people who would buy these homes also desired. In the newspapers of this period along with the advertisements for Hope Valley, one can see a large number of advertisements for automobiles of all kinds that one might buy for Christmas to go with the new house. Advertisements for radios and dishwashers accompany those for roofing in the latest technology. All of this is juxtaposed with ads for authentic-looking false "thatched" roofs.

Hope Valley was platted in July of 1926 in nine sections. The only street names assIgned at that tlme were Devon and Dover. Originally, streets were designated as "Trails;" Windsor was "Trail One," Dover was "Trail Three," Chelsea was "Trail Eight," Rugby was "Trail Twelve;" and so on, At Christmas time 1926, a competition was announced in the Durham Morning Herald inviting Durham residents to suggest fetching names for Hope Valley's "Curving Boulevards and Woodland Drives." Five dollars in gold was offered as a prize for each winning street name; ten dollars (also in gold) for names selected for main drives. With English cottage-style homes abuilding and Devon and Dover as street names to set the tone, the outcome of the competition was less than surprising. No doubt the winning names were selected because it was perceived they would help sell lots to the public, but the contest also enabled Mebane and Sharpe to identify what kind of things appealed to their market. Local shops originally conceived as part of the project were never built, but the prestigious 18-hole golf course laid out by Donald Ross and a clubhouse designed by renowned New York City architect Aymar Embury- -famous for his clubhouses-promised to be big draws. R. R. Griedland was the landscape architect in charge of laying out the grounds for the entire development. The major expansion of Trinity College into Duke University provided Hope Valley with a ready market which the developers pursued. Nearly all of the neighborhood's first homes were purchased by Duke professors.

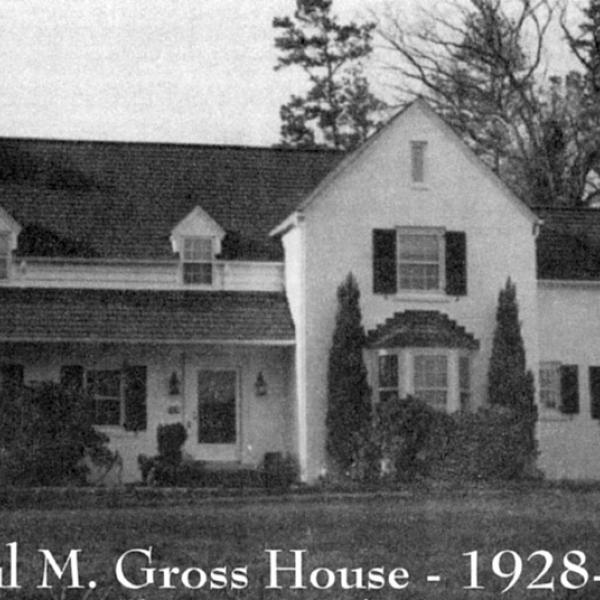

Forrning the nucleus of the development were the ten or so George Watts Carr- designed, English style homes ordered by the developers. Built between 1927 and 1929, they were set in large landscaped grounds on winding streets in strategic loca- tions throughout the neighborhood. Among these early homes were the Branscomb, Gross, and Pearlzweig houses, all of which are on the tour. By 1929, Mebane & Sharpe, Inc. had brought in new partners and reorganized under a new name, becom- ing Hope Valley, Inc. A second wave of houses was built in the early 1930s through the efforts of Hope Valley, Inc. These included the Hubert Teer, D. T. Smith, and Orgain houses, which are also on today's tour. These houses were designed by George Watts Carr, but not in the Tudor or English Cottage styles. By the mid-thirties, the English fashion in residential architecture had begun to wane. The Great Depression diverted the country's attention to things American, and John D. Rockefeller, Jr.'s restoration of Colonial Williamsburg rekindled a keen interest in America's colonial past. The Teer and Orgain houses clearly demonstrate this shift in taste. The Smith House also reflects a departure from Hope Valley's original English country theme. Its Spanish Eclectic style offers a bit of delightful whimsy to the neighborhood.

There were significant and far-reaching differences between the English Garden Suburb and the upscale development envisioned by Mebane & Sharpe. Unlike its English counterpart, Hope Valley was organized around a golf course and country club built on reclaimed farm and dairy land well beyond city infrastructure. It was, therefore, one of Durham's-and America's-earliest examples of the automobile sub- urb. As such, it was an unwitting accomplice in what has become the saga of subur- ban sprawl. But more importantly, it was also a testament to the far-reaching vision of Mr. Mebane and Mr. Sharpe, who foresaw the expansion that would almost certainly take place in the "the Triangle" (called this already in 1926 newspapers!) due to the three universities located here. It is to their credit that they understood that it takes more than houses to build a successful community and so they built into their development the roads, sewer, water, and ameni- ties necessary for a nascent community. Hope Valley is a lasting testament to the optimism of Durham residents of the post WWI generatIon.

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.