Welcome to the 2019 Preservation Durham Home Tour! Whether you're reading up in advance, plotting your route, or navigating the stops on the tour days, this is your digital starting point. Be sure to buy tickets for everybody in your group (available here), get a few extra and invite some neighbors along! Word to the wise, they're cheaper in advance - $20 vs. $25 day of!

This year's theme, Building the American Dream: Durham Homes of the World War Two Era, takes us back to an earlier but somehow familiar phase in our city's complex history. Development was booming, but how it played out raised questions about who it was for. The unprecedented increase in housing stock during those years has left an unmistakable mark on Durham's streetscape, along with lessons for the next chapter in the Bull City story.

Let's start off with a map - here is the wide view of where you're headed (and where some fantastic homeowners have agreed to host you!):

Now that you've got your bearings, take a few minutes to read through the tour introduction below (copied from the official booklet with a few added links and images). If you've already got a sense of the context, you can skip down to the pages for the individual houses.

Owning a home has long been considered a cornerstone of the American Dream, the surest means of building wealth and passing it along to one’s children, but the U.S. wasn’t always a nation of homeowners. In the first part of the 20th century, residential mortgages were unregulated, available only to those who could afford a fifty percent down payment and a five year payback period on a high, variable rate loan. Fewer than half of American homes in 1934 were owner occupied.

The Great Crash that began in October 1929 reduced worldwide GDP by fifteen percent, triggered a daisy chain of mortgage loan defaults and bank foreclosures, and by 1933 caused the failure of one-third of our nation’s financial institutions. The US home ownership rate dropped to around forty percent.

In order to stabilize the banking industry, Congress and the Roosevelt Administration enacted the National Housing Act of 1934. This key New Deal legislation created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and Federal Savings and Loan Corporation, and tasked them with designing and overseeing a nationwide mortgage insurance program. The Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) was also established to help struggling homeowners refinance to longer- term fixed-rate mortgages.

Although much of the American South had been crippled by a severe downturn in agriculture and textiles since the early 1920’s, Durham was an exception. Insulated by the growth of the tobacco industry and the construction of Duke University’s West Campus, Durham’s population soared 277 percent between 1920 and 1940. The pent-up demand of 60,000 residents crammed into some 14,000 housing units met with the sudden availability of 30-year mortgages backed by the United States government. Although the diversion of materials to the war effort continued to hamper construction, the number of building permits issued in Durham rose from 236 in 1932 to 1,689 in 1953.

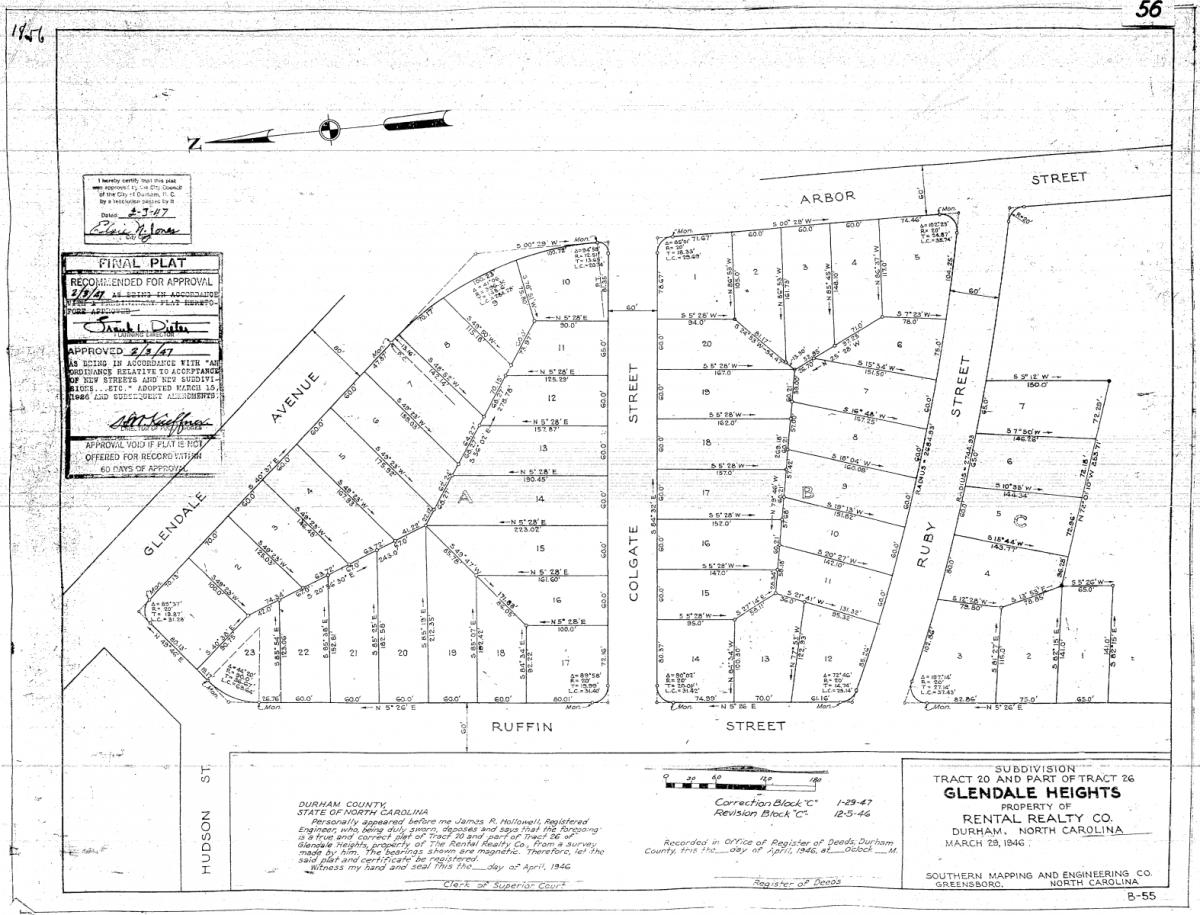

Plat for portion of Glendale Heights near Northgate Park, one of dozens of developments laid out and built in Durham after World War Two. (County Register of Deeds)

With new home construction essentially at a standstill during the Depression, advances in residential design stopped as well. One of the few things happening that captured national attention was the ongoing restoration of Colonial Williamsburg funded largely by John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Exploration of “Early American” styles appealed to an isolationist nation reluctant to get involved in the affairs of a world in turmoil. When home construction began again just before and again after World War II, many architects and homebuyers turned to Williamsburg for inspiration. The resulting homes were comfortable colonials. Many had just simple colonial references, but others were near reproductions of 18th century tidewater Virginia originals. In Durham, architects like

George Watts Carr and

Archie Royal Davis design elegant examples of the Williamsburg style for their clients.

The impacts of federal lending policies in place during this period of remarkable growth are still evident throughout Durham. The FHA not only placed controls on mortgage rates and terms, but also established highly specific criteria for loan eligibility in order to mitigate risk. The FHA advised lenders to invest only in traditional home styles in already stable areas. These policies reduced the likelihood of default but increased the disparity between healthy and declining neighborhoods.

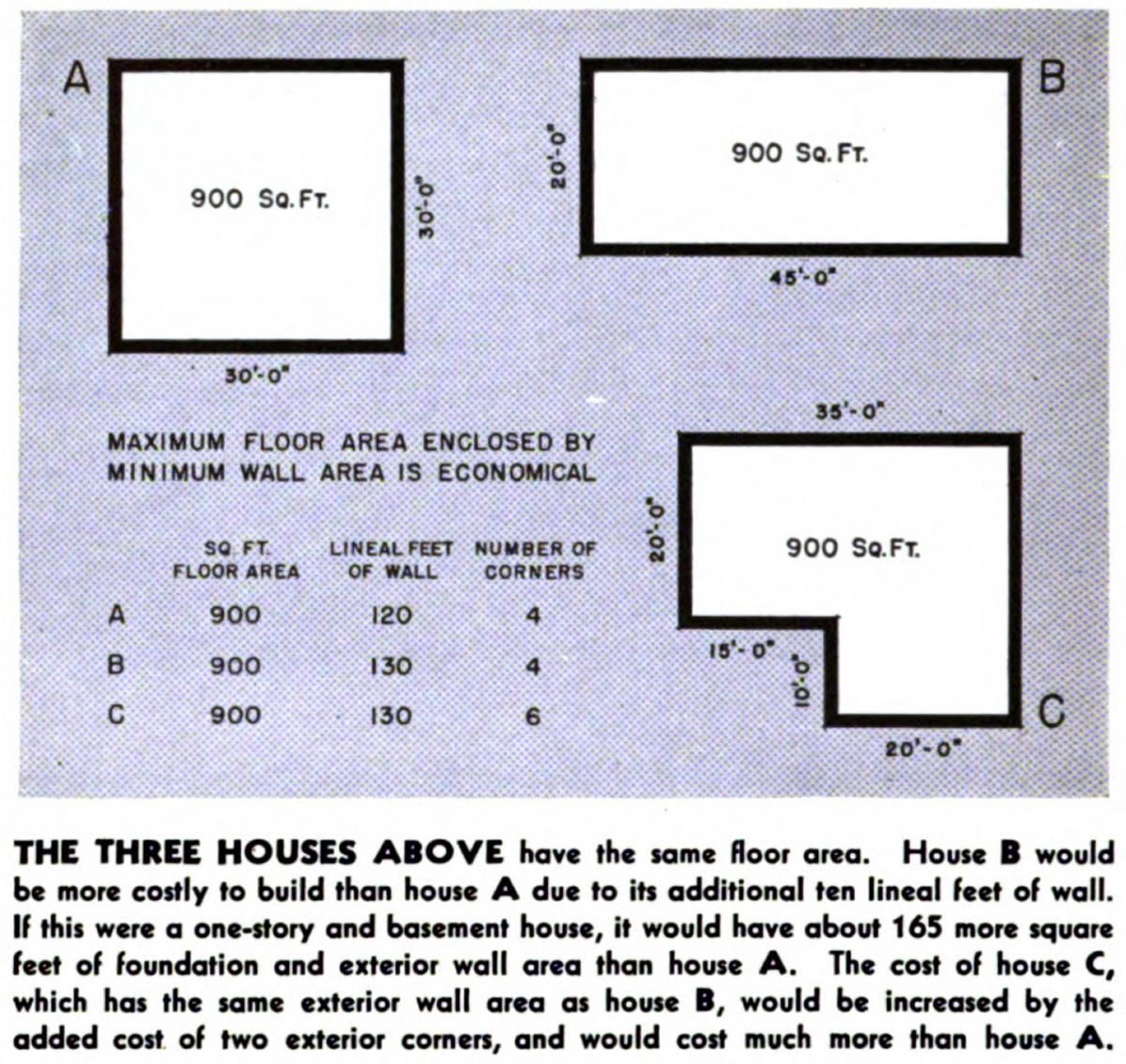

Among the better known FHA Technical bulletins, Principles of Planning Small Houses encouraged the economy found in simple floorplans and standardized building materials. Efficiencies could be found by using the kitchen or living room for dining space, for example, or by placing windows at building corners to increase cross ventilation without giving up wall space. First floor utility rooms were affordable and convenient, while basements were costly and required floor area for steps.

Guidelines for economical construction in the 1940 FHA manual Principles of Planning Small Houses.

Two new housing forms emerged.

Minimal Traditional Homes were usually small and single-story, with simple low–sloped roofs and little exterior ornamentation. They could be built quickly and affordably, and became the defining style of countless postwar subdivisions.

Ranch Homes were often broader, with picture windows, deeper roof overhangs, and a more open floorplan. Often advertised as “traditional outside and modern inside,” the “casual family- oriented style” of the ranch was embraced by magazines of the period such as

House Beautiful and

House and Garden.

Colonial, Minimal Traditional, and Ranch homes began to infill undeveloped lots among the bungalows, and tudor homes of Durham’s older middle class neighborhoods, and to define entire blocks on their outer edges. Older examples predominate in a radial belt 2 to 2.5 miles from Five Points – the northern edges of Watts Hospital, Trinity Park, and Duke Park, the

Rockwood area southwest of downtown, and the

College Heights neighborhood south of NC Central.

Photo labeled "Modern Cottages, Northwest Durham." Looking northwest from Carolina Avenue across Sprunt Avenue in the Watts-Hillandale neighborhood, 1945 (Durham County Library, North Carolina Collection).

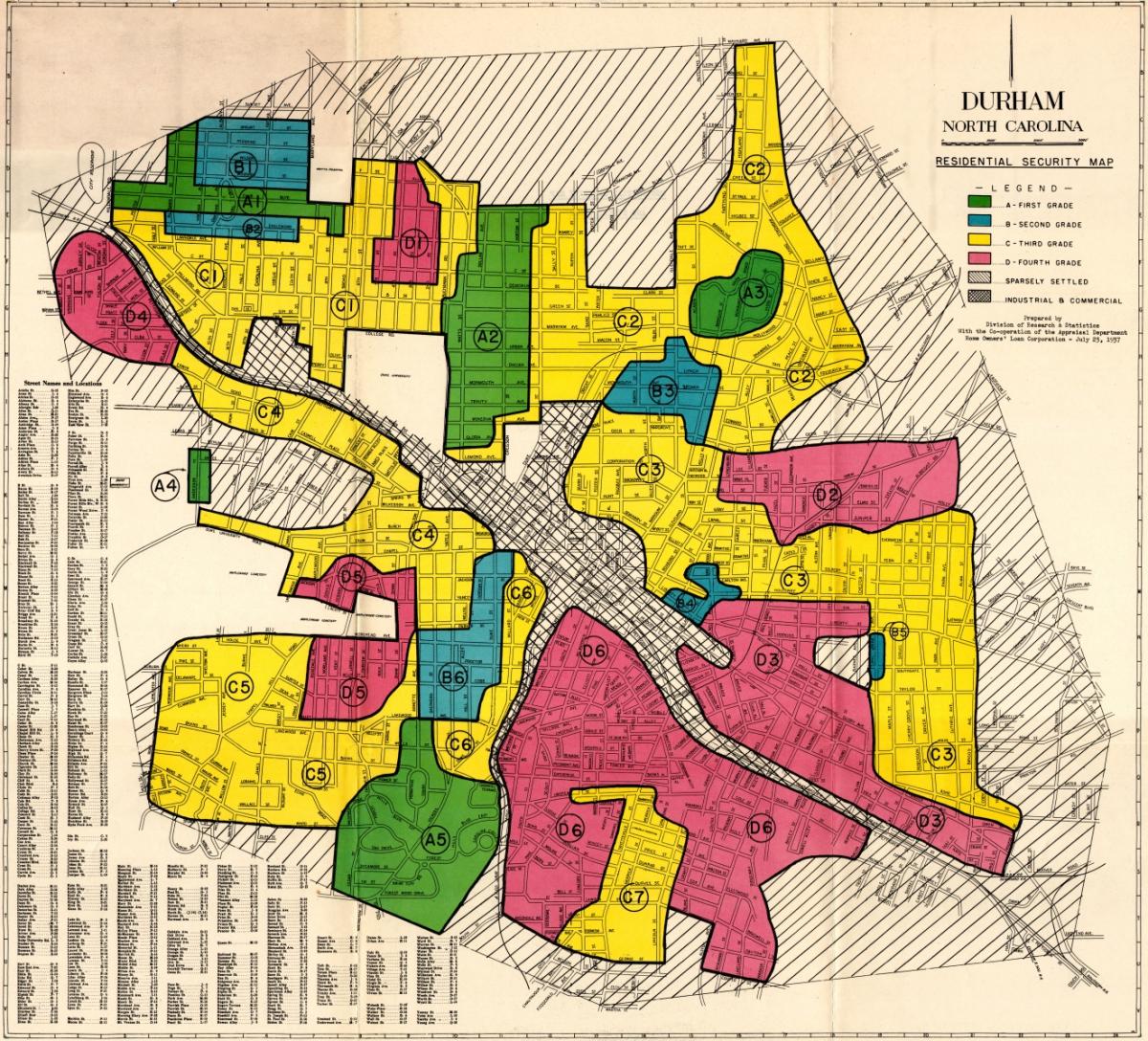

The profound effect of Residential Security Maps is also still felt in Durham. Developed by the HOLC, Security Maps were meant to indicate the level of risk of real estate investments in more than 200 surveyed cities. Based on input from local brokers and appraisers, neighborhoods were assigned letter grades, with FHA guaranteed loans made almost exclusively in the A and B zones. C zones were considered to be in decline and D zones high risk, due in large part to their racial composition, and “obsolete” housing stock. These areas were outlined in orange and red on the HOLC maps, or “Redlined.” It was nearly impossible to get a residential mortgage in a C or D Zone.

In Durham, the D neighborhoods were often the lowest lying areas topographically, the poorest, and almost exclusively African American.

Wall Town north of Duke’s East Campus, the areas surrounding Maplewood Cemetery,

Hicks Town (since eradicated by the Durham Freeway) and the Hillside Park and Grant Park neighborhoods north of NC Central were all D zones, as were the

Morning Glory mill village east of Golden Belt and the

East End to its north. Investment in these areas between 1934 and 1968 was almost nonexistent due to the scarcity of capital.

HOLC redlining map of Durham from 1937 (Courtesy of the Mapping Inequality project, University of Richmond)

Although the use of Security Maps became illegal with the Civil Rights Act of 1968, many of the redlined areas in Durham and across the nation continue to display significantly lower property values, lower rates of home ownership, lower credit scores, and higher rates of economic and racial segregation that their neighbors. Federal policies conceived to stimulate the economy and stabilize the banking industry helped many Durhamites realize their American Dream of homeownership. They also ensured that it remained beyond the grasp of others.

And now, without further ado, the homes themselves!

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.