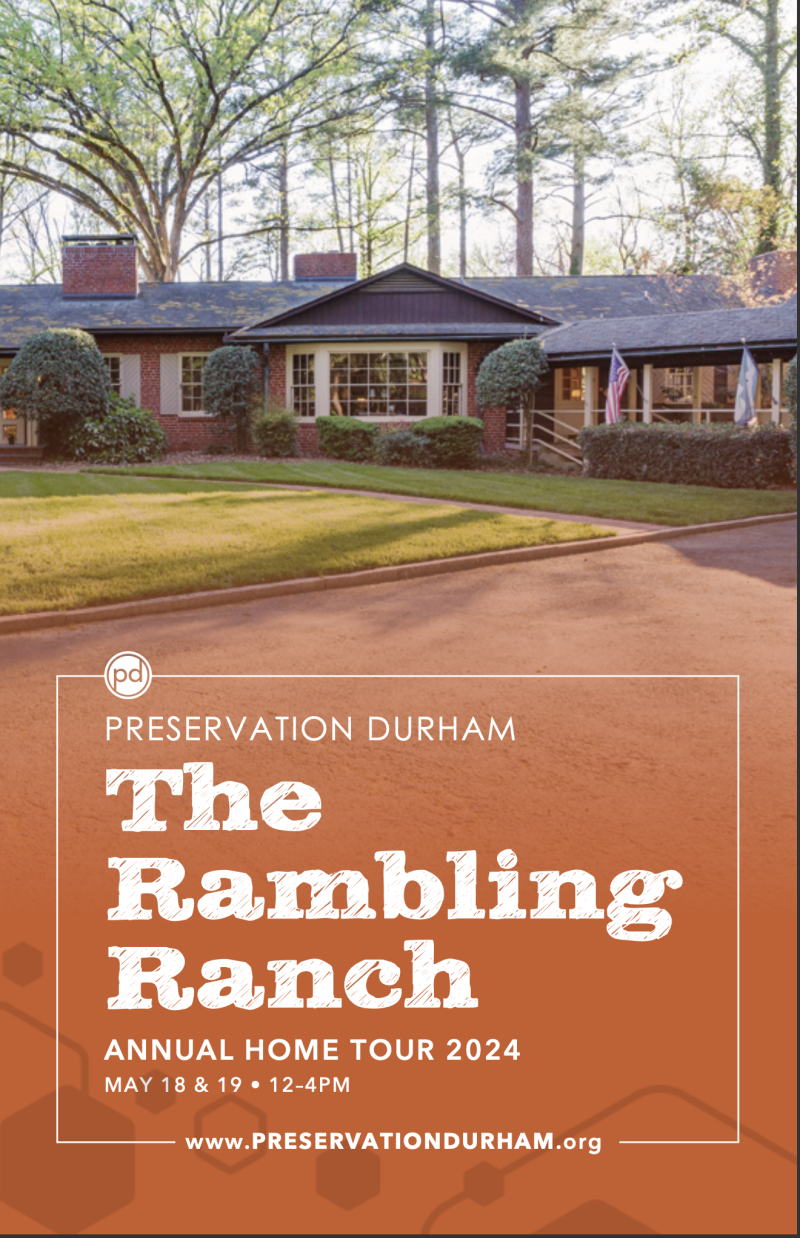

Cover designed by Pam Lappegard. Click cover image to view tour booklet.

By the early decades of the twentieth Century, the tide of western expansion in the United States had reached its limit in California. Soon, a backwash of ideas began to sweep eastward. New ideas about society, art, urban planning, and architecture, warmed under a California sun and carried by a host of new media - railroads, automobiles, aeroplanes, telephones, radio, newsreels, movies, national magazines – brought stories and images of the California good life to every American city, backroad, and byway. Sparkling new cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Diego were hubs of opportunity, free from established class and social structures of the east. Palm trees and orange groves replaced belching smokestacks. Stories of new subdivisions with ample lots and modern homes filled the pages of The Ladies’ Home Journal and House and Garden. Movie stars in sunglasses romped in a land of endless summer.

In residential architecture, California ideas dominated American homebuilding during the early to mid-twentieth Century. Mission Style houses, California bungalows, Ranch houses, and even International Style modernist houses were all incubated in California. Of these, however, it is the practical and adaptable Ranch that has proved to be the most enduring. Based ostensibly on romantic notions of the informal, rustic homes built by early western settlers, the Ranch idea began to take hold in California and the Western states in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Architects like William Wurster, R. M. Schindler, and Henry Greene were heavily influenced by the one-level, rambling, vernacular houses they saw in the California countryside. Their early Ranch designs were clad with adobe and vertical board-and-batten siding and were organized in “L” and three-sided courtyard ranges. Broad shady verandas replaced internal corridors.

When the Great Depression shut down home building in the United States, previously popular home styles like the bungalow and Tudor Revival faded from the scene. To stimulate the building industry, the Roosevelt administration established the Federal Housing Administration and a program of government-insured home loans. To guide buyers, builders, and banks, the FHA published a booklet promoting the construction of small, no-frills homes called Principles of Designing Small Houses. In it were actual house plans and elevations of the types of houses which enjoyed government approval. The two styles pushed by the booklet were a watered-down version of the Colonial Revival Style now known as the “Minimal Traditional” and, because of its simplicity and adaptability, the Ranch Style. Before the FHA program could really get started, the United States became embroiled in World War II. All building materials were diverted to the war economy and domestic homebuilding was halted again.

As the war came to an end, Congress passed the “G.I. Bill of Rights.” In addition to other benefits, the G.I. Bill included a veteran housing program that favored the construction of the small houses described in the FHA guidelines. With years of pent-up demand, a class of eligible veteran homebuyers that ran into the millions, and strict government supervision, hundreds of thousands of new, small Minimal Traditional and Ranch Style homes were built across the country. The strict government supervision that dictated construction also extended to determining who was considered eligible for mortgage subsidies and financing and often the FHA and VA employed discriminatory practices that limited equal use of benefits.

By 1950, however, the government loosened its restrictions on home design and size. Free from postwar restrictions, architects, builders, and their customers across the country turned to the Ranch Style. American home buyers wanted freedom. After years of rigid discipline and cramped quarters in the services, veterans wanted informality and space – space for their growing families, space to relax and enjoy the freedoms they had fought for. The country’s economy was booming. The American Dream of a good job, a new home on a large lot, and a car were attainable for many.

Enthusiasm for the post-war Ranch again flowed from California. In partnership with Sunset Magazine, Architect Cliff May promoted the Ranch Style with dozens of plans and drawings of comfortable one-level, often asymmetrical homes with shallow pitched roofs. With the plans came promotion of the informal California lifestyle. So popular were May’s designs that the magazine published May’s influential book, Western Ranch Houses, in 1946. Another, larger version of the book came out in 1958. Other publications began to promote the Ranch.

House Beautiful and even Popular Mechanics published articles and plans. Other important architects turned to the Ranch for their clients. In New England, Boston-based Royal Barry Wills, master of the New England Colonial Revival Style before the war, designed sprawling rustic, Cape Cod ranches in the 1950s.

The Ranch was perfect. It was adaptable. It could be small or large. It was not only a style of house, but a form. It could be California on the outside and colonial on the inside – or even the other way around. In fact, later ranches are often mash-ups with other styles. There are many Colonial Style ranches with louvered shutters, multi-light windows and Georgian touches around the door. There are French Provincial and even Tudor ranches. From the Ranch Style evolved split-level houses and many Mid-Century Modernist homes are essentially ranches.

Early Ranch Style houses are one-level homes usually oriented parallel to the street. These houses emphasize horizontal lines and often have shallow-pitched hip roofs with deep overhanging eaves that run all the way around the house in an unbroken line. Entryways are often recessed and tucked under the eaves obviating the need for a projecting front porch. Horizontal lines are often repeated in siding joints and window divisions. Smaller Ranches might present a symmetrical front to the street, but larger houses invariably tend to “ramble” in an organic way with articulations and variations in materials. Ranches were built in every material, sometimes mixing brick with wood or shingle siding. Larger ranches often have massive internal chimneys arranged axially or transverse to the main axis of the house. There is a wide variety in fenestration in Ranch Style homes. Early Ranches often have steel casement windows, sometimes placed to wrap playfully around a corner of the house. Sadly, these interesting windows have often been replaced with more energy-efficient, but less architecturally appropriate units. Picture windows were popular. They joined living spaces with the street or the garden in the way porches did in earlier designs.

The Ranch is a purely American design. Its history is tied to the American romance of the automobile. In the 1910s and ‘20s, bungalows were designed to fit the narrow lots in streetcar subdivisions. The automobile was a luxury beyond the reach of many families. After World War II, everyone wanted a powerful American sedan or wagon. The automobile bridged the gap between the suburbs and city center. New subdivisions at the city’s edge were designed with the car in mind. Lots became larger and Rambling Ranches were designed to take advantage of them. In older, inner-city neighborhoods, narrow lots left vacant during the Depression and the war were recombined to accommodate the Ranch houses everyone wanted. The Ranch house itself was designed to serve the family car. Grandfather’s Model T was parked in a separate frame building at the back of the lot. That would never do for the proud owners of the big Fairlanes and Bel Airs of the 1950s. Ranch architects replaced the detached garage with a “carport” engaged to the house. The family and their vehicle lived under the same roof. The carport made the kitchen door the main access point to the home. The formal front door, like the formal living room, was just for visiting company.

The hallmarks of the Ranch interior are informality and modernity. Earlier homes had formal living and dining rooms. The kitchen, a workspace, was hidden away at the back. In homes of the wealthy, there might be cramped spaces for hired help. In a Ranch house, the living and dining rooms are often joined together. This was a practical necessity in the smaller FHA version of the Ranch, but it carried over in many larger-scale, later houses. A Ranch kitchen is a family space. It is larger, with room for cooking, dining, and socializing. In many Ranch Style houses, the only dining area is in the kitchen. Guests were expected to join the family in the Ranch kitchen. Instead of being at the back of the house, in some Ranches, the kitchen is located just inside the front door. In others, the kitchen is joined to a den or family room with an opening between the counter and the cabinets.

The evolution of the Ranch Style is intimately connected to the growth of television. For centuries, the focal point of any dwelling was the hearth – the source of heat and light. Rooms were designed around the fireplace. Furnishings were invariably organized to encircle it. Even when reliable central heating became available in the early-twentieth century, even modest homes were designed with a not-entirely-necessary hearth as the living room’s focal point. In the evening, the family gathered around the hearth. They talked, rested, read, did mending or other work. The introduction of the phonograph, and later the radio, did not upset the ancient arrangement. These devices may have displaced the upright piano, but not the hearth.

The television, however, was different. It must be watched and heard. All the furniture must face it. Family dinners moved from the dining room to wherever the T.V. was. When the television became universal, the adaptable Ranch was ready. In many Ranches, the vestigial fireplace was simply eliminated to make room for the RCA console. In other Ranches, the formal living room retains its fireplace, but the T.V. reigns supreme in the “den.” The idea of an informal living space called the den did not originate with the Ranch. It grew from the idea of a small, informal library or office in middle- and upper-class homes of the 1910s and ‘20s. It was often paneled with formal, high-end woods or with more rustic materials. In the 1930s, ’40s, and ‘50s, dens and knotty pine went together. Television was perfect for the den. Consequently, architects made dens bigger and living rooms, if they survived at all, smaller. The fireplace might also move to the den with the T.V., but it played second fiddle. In a Ranch, the fireplace was often surrounded by exposed brick and given a raised hearth with cushions to provide overflow seating to watch the T.V.

In Durham, in the 1950s, vacant lots in unfinished subdivisions became homesites for new Ranch Style homes. Ranches, large and small, began to fill in the northern edges of Trinity Park and Duke Park. Ranch houses also began to appear on large lots in Forest Hills and Hope Valley. Throughout the 1950s, ‘60, and ‘70s, whole subdivisions were built around Ranch designs. Excellent examples of Ranch houses can be found in neighborhoods sprouting off North Duke Street and Guess Road. Concentrations of Ranch Style houses appear in the new sections of Rockwood Park and Duke Forest. Although the Supreme Court struck down racially restrictive covenants in 1948, Durham neighborhoods remained substantially segregated, in large part due to the redlining practices encouraged by the FHA. Nevertheless, the Ranch became the house of choice among the expanding postwar African-American middle class. A new style, free of European and Colonial symbolism, the Ranch appealed to Durham’s Black elite. Modest to monumental Ranch style homes are peppered throughout the newer parts of the College Heights and Emorywood Estates neighborhoods.

While many of Durham’s Ranch Style homes were built from stock plans published by designers following the example of Cliff May, Durham’s finest Ranches were designed by prominent local architects like Robert Winston Carr, Joe Hakan, George Hackney and Charlie Knott. We are fortunate with this tour to be able to show you homes by some of these designers. The seven homes selected for this year’s Preservation Durham Home Tour display nearly every design element and nuance of the American Rambling Ranch. We know you will join us in thanking our homeowners for opening their homes and our eyes to this important period of American architecture.

Because of its adaptability, practicality, and informal comfort, the Ranch Style endured from the 1930s through the 1980s – a longer run than any of its bungalow and period revival predecessors. Today, classic Ranches are sought after by mid-century modern enthusiasts. With the prevalence of today’s small-lot subdivisions, however, the Ranch is less popular with current developers and national homebuilders. Nevertheless, Ranch ideas of openness and informality still shine through in new home designs.

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.