From the NC Architects entry:

One of the first leaders in the state's early 20th century architectural profession, Charles Christian Hook (February 18, 1870 - September 17, 1938) moved to Charlotte as a young man in 1890 and practiced in the "Queen City" for the rest of his long career. He was Charlotte's first fulltime professional architect, and one of the most prolific architects in the state in the early 20th century. His practice encompassed three partnerships--Hook and Sawyer, Hook and Rogers, and Hook and Hook--as well as work on his own. His firms' activities extended throughout Piedmont North Carolina and beyond, as far east as Greenville, west to Morganton and beyond, north to Spray and Eden near the Virginia border, and south into South Carolina. Although Hook is best known for his work in the Colonial Revival style, his work encompassed all of the popular styles and building types of his times, from the Queen Anne, Romanesque Revival and Shingle styles through Italianate, Châteauesque, and Renaissance and Neoclassical Revivals, and by the 1920s he was working in a suave and monumental Beaux-Arts classicism. He exemplified the growing tendency of architects to promote themselves through local newspapers and regional journals, especially the Manufacturers' Record of Baltimore, a journal devoted to publicizing news of progress in the South. Between 1891 and 1910 alone, he and his partners published notices for more than 200 projects in that journal, and many more followed in subsequent decades, so that his firms' total production probably reached as high as 800 to 1,000 projects. (Only a few of these are included in the building list; there are many others for which scant information is known.)

Born in Wheeling, West Virginia, Hook graduated from Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri in 1890. Why he selected Charlotte, North Carolina, as his destination is not known, but he moved promptly after graduation to the growing industrial and commercial city, where he was listed in the Charlotte city directories as an Instructor of Drawing at the Charlotte Graded School in 1890, 1891, and 1892. At that time, many ambitious entrepreneurs and others were drawn from far and wide to try their luck in the New South city. In 1891, he began his career as an architect, and continued working until his death in 1938. He married Ida McDonald of an established Charlotte family in 1896, and they had two children, Walter and Rosalie.

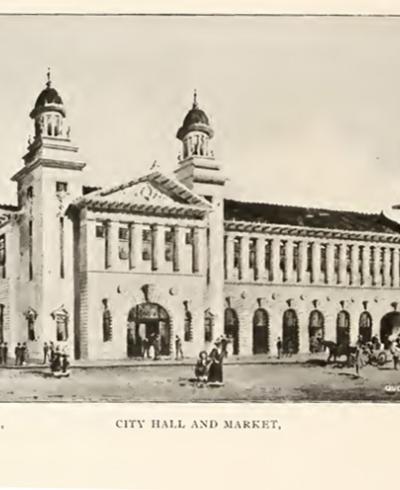

Eager to make his mark in the growing city and region, Hook published his first (known) entries in the Manufacturers' Record shortly after arriving in Charlotte, while still teaching at the Charlotte Graded School. In the October 24, 1891, issue, he reported that he had made drawings for a residence for S. Wittowsky in Charlotte, a residence for F. B. McDowell in Blowing Rock, and an Episcopal Church in Blowing Rock, suggesting that he was already attracting prestigious clients. Whether any of these was built is not established. Between 1891 and 1899, Hook listed thirty-two projects in the Manufacturers' Record, including residences, schools, municipal buildings, hotels, and commercial buildings. For some, he reported only that he was making or had made drawings, while for others a contract had been awarded for construction. From 1891 to 1910, nearly every issue of the journal contained a notice from Hook, and more followed in subsequent years.

Hook also used local newspapers to educate the public about architecture while publicizing his practice. Like many Americans, he found that his trip to the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago inspired affection for the white-columned porticoes of the Colonial Revival and other associated revivals. Upon his return from the fair, he suggested in an article in the Charlotte Observer that readers should visit Washington, D.C. on their way to or from the exposition, to learn about the classical orders of architecture and the placement of buildings in well-organized landscapes. In the September 19, 1894, Charlotte Observer he presented the "Typical Southern Home" he had designed for J. Frank Wilkes, "after the true classic style of architecture, which at one time predominated the south and is again being revived"--a design suggesting that Hook was the "father" of the Colonial Revival style in Charlotte.

Complementing his publicity in print, Hook was a shrewd businessman who made important contacts early in his career. One of his earliest associations was with the Charlotte Consolidated Construction Company ("the 4 C's"), the developers of Dilworth, Charlotte's first suburb. Lead developer Edward Dilworth Latta initially employed Hook to design several "new-style" houses for the neighborhood to promote sales. Among the first residences Hook planned in Dilworth was the Mallonee-Jones House (1895), home of another developer of the suburb and one of Hook's last works in the eclectic Queen Anne style. Hook continued to design houses for Dilworth in a variety of styles over the years.

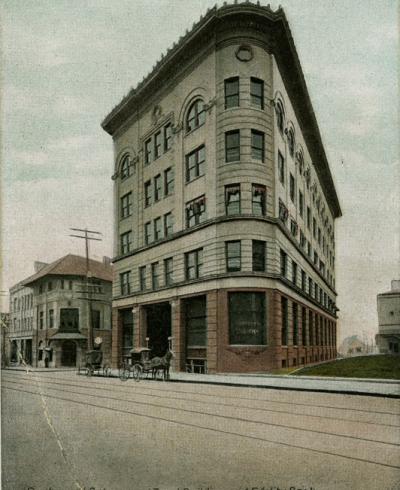

By 1898, Hook had established the first of his three architectural partnerships. Hook joined with New Yorker Frank McMurray Sawyer to form Hook and Sawyer, which operated from 1898 to 1905 and reported 103 projects to the Manufacturers' Record. In this, as in later partnerships, it is difficult or impossible to know which man designed which buildings or what their division of tasks may have been. The firm employed a few other workers, probably draftsmen, and a boy named Kenneth Whitsett to run blueprints. Whitsett later recalled, "I could only work on days when there was sun. I ran blueprints onto the main roof of the Trust Building, and waited for the sun to come out. . . . I'd watch people on the street, and a man plowing out on a farm. When he got to the other end of the field, I'd pull the blueprint in." (Kratt and Hanchett, Legacy). As partners, Hook and Sawyer planned numerous buildings in Charlotte, both downtown and in the new Charlotte suburbs of Hill Crest, Colonial Heights, Wilmore, and Piedmont Park. They also gained a series of major commissions that extended their reach far beyond Charlotte.

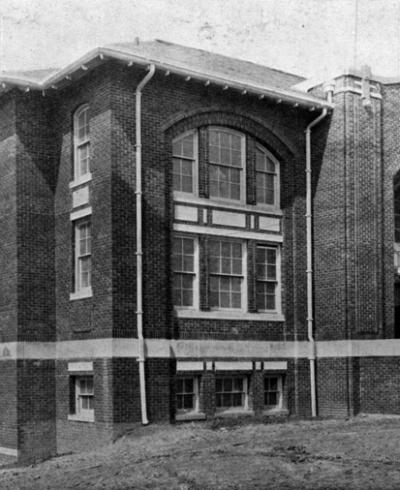

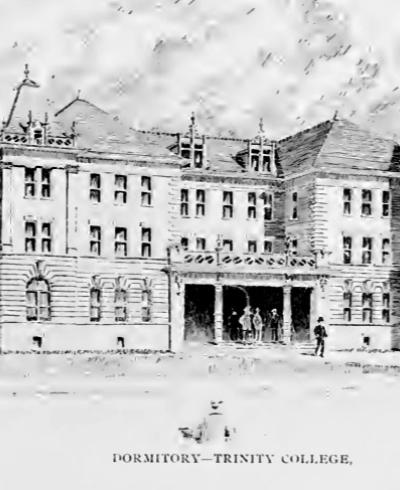

In 1902 the pair published Some Designs of Hook & Sawyer, Architects, 1892-1902, which featured houses, apartment houses, business buildings, and hotels, as well as institutional and government buildings. The booklet showed projects as far away as Greensboro, Durham, Greenville, Spray, and South Carolina. Some of the designs predated the partnership, however, thus making specific attributions uncertain. (In addition, Hook continued to report his own works to the Manufacturers' Record well after he began the partnership with Sawyer.) Especially important, the Hook and Sawyer booklet showed that in addition to the Colonial Revival style, Hook and Sawyer worked in a broad range of styles, including various amalgams of Italianate, Romanesque, Queen Anne, and Shingle styles. They especially favored public buildings with campanile-like towers, Flemish curved gables, and decorative brickwork. Although several of their most dramatic and eclectic designs were built, few have survived, thus skewing the standing record of the firm toward the conservative and the classical.

Hook and Sawyer also published plans and articles in the Charlotte Observer. In the December 20, 1903, issue Hook accompanied their drawing of a Colonial Revival style house with a lengthy commentary suggesting links between the architectural and political trends of the time:

"In ante-bellum days when a home was built of any pretentions [sic] the owner and designer as a rule was an educated gentleman of refinement, and being familiar with the classics and having other colonial work as models took pains to preserve the proper proportions and details in general. After the great conflict and things being reversed in general we find in greater reversal in architecture than any other sign of the times."

"Why was it? Because the illiterate and unrefined being new to wealth desired display more than purity, and the cultured and once wealthy were either too poor to build or were too busy during the reconstruction period that they had no time to devote to art. So all consented to do the most foolish of all things, that was to delegate as the designers of their homes, the most ignorant class of men, in fact, any jack-leg who could wield a hatchet and saw was considered thoroughly competent to do one of the important of all things for a man, i.e., design his home. As the times have advanced all colonial details and proportions were discarded as being "old timey," the jack-leg carpenter with the deadly jig-saw ran riot throughout the land. Finally an attempt was made at better architecture by the adaptation of the Queen Anne style and French and Italian villas, but these were quickly brought into bad repute by the ever convenient jig-saw artist. Out of all of this chaos we again have a revival of the colonial. Its symmetry, restfulness and good proportions generally caused it to rise superior to all other schools of design."

"Beyond doubt the colonial style in its purity expresses more real refined sentiment and is more intimately associated with our history than any of the styles mentioned. It is not only an association of English history with our own but it expresses authentic memoirs of the American people themselves. We wish not to condemn any other style, for in fact, we are personally partial to the ingenious adaptation of the composite; but we must condemn the garbled colonial architecture. The use of colonial details in the composite style is accepted as in good taste, but where we attempt the colonial with the stately portico we are, bound to refrain from sacrificing purity of design and symmetry, to fashion and display."

Beyond his promotion of the Colonial Revival, Hook and his partners were well versed in all the architectural styles of the time and could render any of these to suit the client. By 1904 the partnership had expanded sufficiently to establish offices in both Durham and Greensboro. In 1905, however, the partnership dissolved.

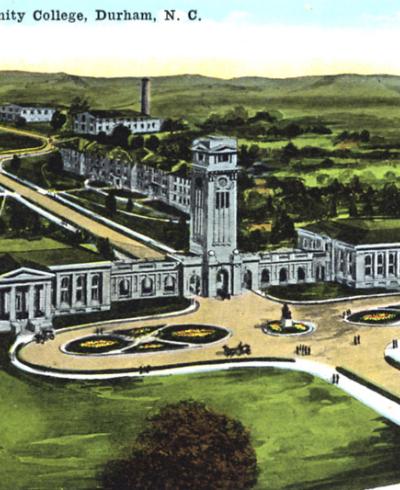

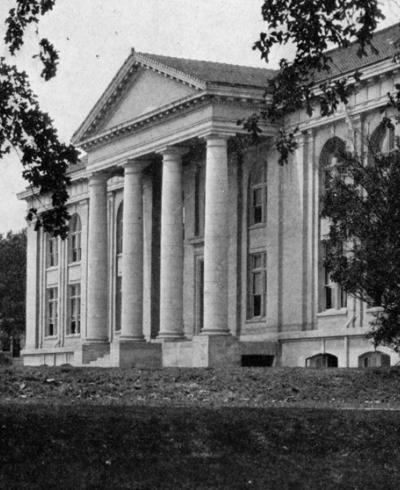

Later in 1905, Hook established a partnership with Willard G. Rogers. Rogers had moved to Charlotte from Cincinnati, Ohio, around 1900 as an architect for the engineering firm of Stuart W. Cramer. The partnership of Hook and Rogers picked up where Hook's previous firm left off and covered the gamut of building types and styles. Especially important was their collegiate work during a period when both public and private colleges and universities were expanding. Their collegiate work included prestigious commissions at Trinity College (predecessor of Duke University) in Durham, Davidson College in Davidson near Charlotte, Queens College in Charlotte, Guilford College in Greensboro, the State Normal and Industrial School (now University of North Carolina at Greensboro) in Greensboro, St. Mary's School in Raleigh, and, with New Bern architect Herbert W. Simpson, the newly established East Carolina Teachers College (now East Carolina University) in Greenville. Their designs for these continued within the generally classical and Colonial Revival modes Hook and Sawyer had established. Some were in red brick, others in tan brick, and many had tile roofs. Hook and Rogers's productive partnership continued until 1916, when the two men decided to operate independently.

One of Hook's longest-running architectural relationships, continuing through various partnerships, was with Trinity College (later Duke University) in Durham. From 1895 to 1925, Hook served as architect for the young college, working directly with the college president William P. Few. His buildings were of brick in his characteristic free classical design vocabulary, some with tile roofs. As discussed by Charlotte V. Brown in Architects and Builders in North Carolina, Hook's surviving correspondence with Few (from 1910 onward) is extensive and informative, illustrating their ongoing relationship, issues in the design process, and the means of communication in the period. Few, like clients of other architects, wished that Hook could provide designs more quickly and visit the work site more often. But Hook assured him on November 11, 1912, that his speed of design and frequency of visits was better than the norm. "The custom is to visit about every two or three weeks, we visit about every week or ten days, we are told by contractors and other architects, that we visit the works more frequently than others." Later Few stated that Hook had "from first to last given entire satisfaction." Although in the 1920s and 1930s the firm of Horace Trumbauer and his principal designer Julian Abele transformed much of Duke's East Campus and created the new West Campus, some of Hook's work on Duke University's East Campus still survives, most notably the East Duke Building and West Duke Building.

As well as forming lasting relationships with institutions, Hook and his partners also built a prestigious and rewarding clientele among the state's New South business leaders. Prime among these was the Duke family, state and national leaders first in the tobacco industry, then in textiles and hydroelectric power. Hook's work at Trinity College tied him to its chief sponsors, the Duke family, and he also designed civic buildings funded by the family. He planned a house in Durham called Four Acres for Benjamin N. Duke, and later expanded a residence to create the James B. Duke Mansion in Charlotte. For Duke business associate James Stagg, he planned Greystone, one of the few surviving pre-1920s mansions in Durham. Hook also built for industrial leaders farther west such as the Lineberger family in Gaston County, and hydroelectric power developer E. B. C. Hambley in Salisbury.

During this period, Hook led in promoting professionalism in architecture. The first organization of professional architects in North Carolina came in 1906, when a small group of primarily Charlotte architects including Hook formed the North Carolina Architectural Association (NCAA). In 1913 several architects succeeded in chartering the North Carolina Chapter of the AIA (NCAIA) with twelve members. There were tensions between the two associations, and Hook was one of the Charlotte architects who did not readily join the NCAIA. Two years later, however, with the support of both groups, "An Act to Regulate the Practice of Architecture and Creating a Board of Examiners and Registration of Same" was passed, making North Carolina one of the first states in the nation to license architects. As a member of the NCAA, Hook served on the first North Carolina Board of Architectural Registration and Examination, established in 1915. The board consisted of members from both the NCAA and the NCAIA. Hook was one of the first licensed architects in North Carolina. His license certificate, issued in 1915, was #15 in the official registration book of the North Carolina Board of Architecture, one of the early group of men who were licensed in the state based on their having been in professional practice prior to the licensing act of 1915.

After 1916, Hook practiced alone until 1924, when he formed a partnership with his son Walter. The firm of Hook and Hook became one of the most reputable and prolific in Charlotte and the Piedmont, and were especially well known for their work in hospital and health facilities. The partnership lasted until the elder Hook's mysterious death in 1938. On September 17 of that year, the architect went to his office despite suffering from vertigo that morning. At the office he told a mail carrier that he was feeling ill, and went into the washroom to splash his face. When he leaned over to replace his towel on the towel bar he evidently fell out the window. The coroner found that the 12-story fall was an accident. He was survived by his wife, Ida, his son and partner Walter, and his daughter Rosalie.

Walter Hook continued to practice architecture in Charlotte until his death in 1963. He was a respected leader in the field who specialized in health facilities. His work included Mercy Hospital, Carolinas Medical Center, and Presbyterian Hospital in Charlotte, and the Veteran's Administration Hospital in Salisbury. C. C. Hook's grandson, Rosalie's son Charles Gwathmey, also followed the architectural tradition of the family. He became one of the leading postmodernists in the country during the late 20th century as the principal for Gwathmey-Siegel Architects, a firm based in New York City.

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.