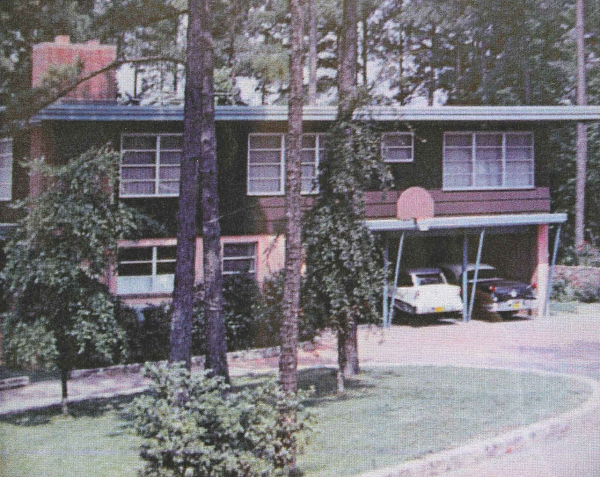

(photograph courtesy of Alex Maness)

From the 2012 Preservation Durham Old Home Tour booklet:

When Mildred and Dillard Teer decided to leave their traditional home in Trinity Park and build on their Beverly Drive lot, they were not wedded to a style concept, but they knew they wanted an open floor plan with public spaces flowing into one another. They took their ideas to architect and friend, Robert Winston Carr. Carr, no stranger to the colonial and other revival styles that were the bread and butter of the firm founded by his father, George Watts Carr, determined that this project demanded something other than a traditional style house. Instead, Carr chose a modernist design that is now called the American International or Contemporary Style. Its emphasis on long horizontals and irregular massing allowed him to fully exploit the dramatic, steeply sloping site.

The International Style is marked by flat roofs, asymmetrical organization of details, cantilevered projections, metal casement windows flush with outer wall surfaces and the absence of formal entryways. Exterior walls are usually white stucco without copings or decoration. As it evolved in American residential design, the style kept its asymmetry and flat roofs but replaced the austere white stucco with a softer, richer mixture of brick, different woods, and other materials.

A tour of the Teer House must begin with a walk around the exterior of the house, following the sweep of the horseshoe bend of Beverly Drive. Beginning at the lower – or eastern – end of the property the guest sees the house emerge from the slope of the hill in a series of horizontal terraces. Each level is emphasized by the broad, metal cornice at the roof line. Unlike the International Style houses of the pre-war period, the Teer house has deep over hanging eaves. Instead of plain stuccoed walls, the house is clad with materials that provide contrast in color and texture. The upper floor is clad with dark, wide cedar shingles, and the floor below that is covered with lighter-colored vertical board-and-batten siding. The whole is supported by a basement terrace of white block that rises up to the house. The door is centrally located in the western façade that is balanced without symmetry. The door, pierced by three square windows of equal proportions, is set in a reeded frame and flanked by narrow sidelights. The entryway is surrounded by a wall of soft orange-pink brick, and the whole is sheltered by a deep, overhanging eave supported by angled-metal pipes.

The rich and innovative use of complementary and contrasting materials outside is carried through to the interior. Dillard Teer insisted that there be no plaster or sheetrock inside his house. Standing just inside the front door, the visitor sees vertical wood paneling, brick, bamboo, painted wood, and striated plywood paneling stained with deep turquoise. The ceiling is covered with tiles. From this spot the visitor is invited to each of the three principal levels of the house. Ahead are the large kitchen and dining area. To the right, down a short flight of stairs is a sunlit passage leading to the living room. At the end of this view is another door containing the stacked squares that mark the entry way. As you move from room to room and level to level, note how the wall materials, ceiling heights and window organizations change. In this room, formality is signaled not by a hearth or by time-honored classical elements, but by the drama of high ceilings, rich wood paneling, and a wall-and-a-half of floor-to-ceiling windows. In the den behind the large living room, the walls are faced with sheet paneling covered with a rich, dark, book-match veneer in exotic wood. This is a personal, more contemplative room.

The kitchen is nearly all original. Laid out as a generous, live-work space, its surfaces are also wood and man-made laminate materials. The turquoise of the painted stair risers and coping is repeated here and is the only color used to decorate any of the vertical interior surfaces. The current owners have plans to update the kitchen and have taken significant pains to preserve the character of the space.

Upstairs are five bedrooms, organized along the two legs of the L-shaped plan. These rooms are spacious and, like the rooms below, display a variety of wood wall coverings that make each room a distinct space. The floors upstairs are cork and carpet. Again, the turquoise paint provides the only color contrast. Some of these rooms have a fine view of the original kidney-shaped swimming pool located in the natural fold of the earth at this end of the site.

The Teers had hardly moved into their new home before they expanded it in 1955 by adding a sixth bedroom over the den below.

Mildred and Dillard Teer were both children of prominent Durham families. The Teers excelled in road building and other major construction projects. Dillard began working for the firm in 1938 and became an officer when his father, Nello Teer, Sr., retired. Before her marriage to Dillard in 1942, Mildred was a Roycroft. Her father ran one of the largest of the tobacco market warehouses that once lined the streets just north of downtown. Mildred and Dillard Teer were just in their thirties when they built the house at 40 Beverly Drive. It remained their home for 50 years.

Today – even after 60 years – the house the Teers and Robert W. Carr created ranks as Durham’s most important modernist dwelling and is among the city’s small portion of genuinely important historic buildings.

Two mid-century shots of the Teer House that were submitted in the application for Local Landmark status:

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.